South Sudan conflict: The hungry emerge from swampland for aid

- Published

The BBC's Alastair Leithead is in the rebel-held town Thonyor in Leer County

Three years of civil war in South Sudan have driven thousands of families into the marshes of the Nile to hide from the fighting. A famine has been declared some parts. The BBC's Alastair Leithead has been to the rebel-held town Thonyor in Leer County, where people have been told to gather to get help.

They emerged from the marshlands of the Nile in their thousands, as word spread that help had come.

Forced by fighting to live on the isolated islands of the Sudd swamps, they have been surviving for months on wild plants.

Now they sat on the dry, cracked earth in long lines under a brutal sun - mostly women and children - waiting to register for the food aid which would be air-dropped in a few days time.

"We are only surviving by eating wild honey and water lilies from the river," said Nyambind Chan Kuar as she sat with 16 of her children and grandchildren.

"The fighting has been disastrous - children have been killed, they are taking our things, our cattle, our goats, taking everything, even though we have nothing to do with this war."

Thousands have been hiding from the fighting in swampland

Each person is given a card that entitles them to 30 days of food rations when supplies arrive. Their finger is then stained with ink to avoid duplication.

"People are dying because of this hunger," said Mary Nyayain. "That's why we are here queuing for these tokens."

The town of Thonyor in Leer County was chosen as the central point for distributing aid after long negotiations with both sides in the civil war.

It's one of the four counties in Unity State suffering pockets of famine, which the latest hunger assessment says is affecting 100,000 people.

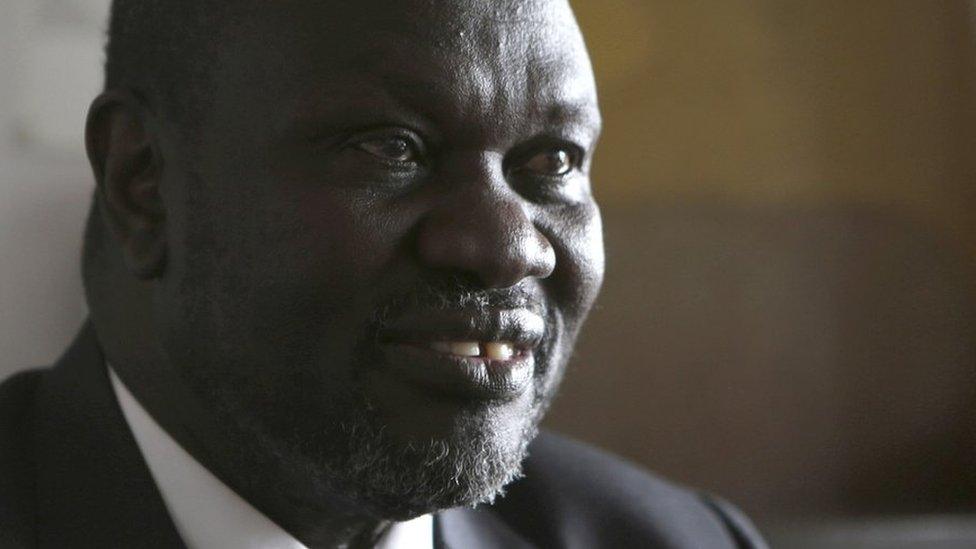

Leer is the birthplace of the former vice-president turned rebel leader Riek Machar which is perhaps why it has been the centre of so much fighting.

People in Unity State say they have been eating water lilies to survive

Thonyor is controlled by the rebels or the "IO" as they're known - forces "In Opposition" - but the government troops are just 20 minutes up the road.

"The war has been so difficult for us," said another woman waiting in line for a cholera vaccination.

"Especially for the old women who are not able to run to the river to survive in the islands. Our cows and goats were taken so that's why we are only able to survive through the food agency."

Under each tree is a different medical post - with health checks for the children.

The worst cases of malnutrition are treated straight away.

About 36,000 people are expected to be registered - but the UN says thousands more are cut off by rivers or fighting

"You may think this child is actually very healthy - he's fat, he's looking OK," said James Bwirani from the Food and Agriculture Organisation.

"But this is just water accumulating in the body and he has not been consuming adequate food for some time."

The child has a distended belly and his face and limbs are swollen.

"If left untreated for between a week to two weeks, this child is going to be dead," Mr Bwirani said.

The UN World Food Programme (WFP) is coordinating this emergency response, expecting about 36,000 people to come in from the swamps for help.

Leer County is the birthplace of rebel leader Riek Machar, who has fled the country

But there are many thousands more who are too far away, cut off by rivers or in areas where the government and the rebels have not agreed to provide access.

"For many, many months humanitarian agencies have not been able to make it into this area. This is first time we're doing so," said George Fominyen from the WFP.

"Without safety, without assurance of security for the people that are in need and the aid workers, we'll be having a catastrophic situation down the line."

The UN describes this as "a man-made famine" - created by the civil war which has divided the army and the country largely along ethnic lines.

A political row between President Salva Kiir and Mr Machar led to killings in the capital and fighting which has spread across the country.

The UN says the "man-made" famine has been caused by the civil war

The war has displaced millions of people, many into neighbouring countries, and 40% of the population now depends on international aid.

Mr Machar fled South Sudan in July when a fragile peace deal collapsed.

He is currently in South Africa, unable to return but apparently still commanding his troops by phone.

Leer county commissioner Brig Gen Nhial Phan said there won't be peace until Mr Machar is allowed back to take part in a proposed national dialogue.

He believes President Kiir wants to drive people out of his county.

Leer County officials accuse President Kiir of orchestrating the bloodshed

"The government kills people - their militia is raiding, taking cows, killing and burning the church and the houses, forcing people into the islands," he said.

There are scorch marks where the market used to be and the remains of a Medecins Sans Frontieres clinic, destroyed when the government forces took the town for two days last November.

By getting help in fast, aid agencies hope to pull this region back from famine and stop the famine from spreading - if they are allowed to access to the worst affected areas.