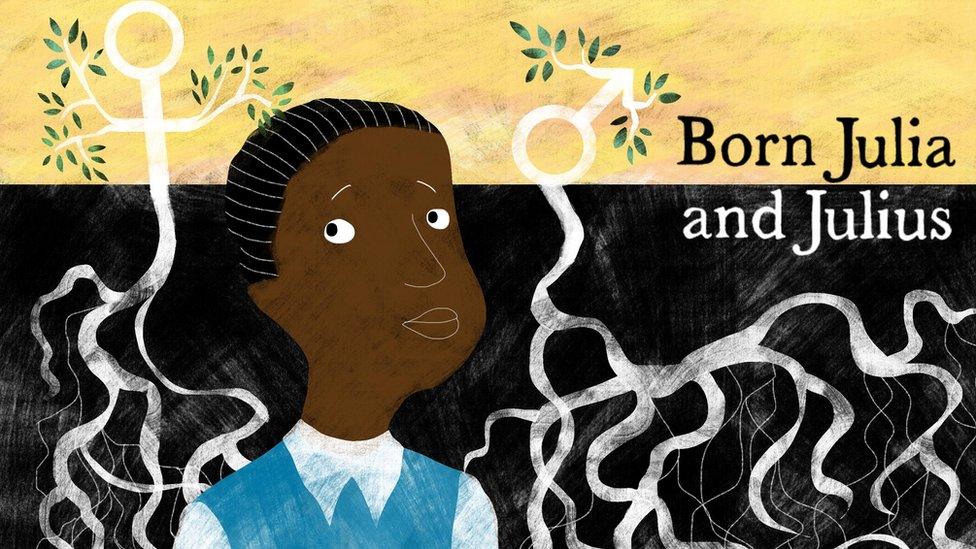

Becoming Julius: Growing up intersex in Uganda

- Published

Julius Kaggwa was born intersex, which meant it was not clear if he was a girl or a boy. It made for a confusing, isolating and sometimes dangerous childhood growing up in the conservative society of Uganda.

"I was brought up as 'Julia' but I never felt like I belonged," Julius, now 47, tells the BBC.

Around the age of seven, he began to work out that his body was different to most other children's.

"Not much. Just that I was a little different and that this could cause me to be ridiculed."

Julius comes from what he calls an ordinary peasant family, with a religious background.

His mother was loving and protective and his wider family "accepted and still accept me unconditionally".

'Considered a curse'

This is not something that can be taken for granted with intersex children in Uganda, he says.

"In our culture, being intersex can be considered a curse, and something to get rid of."

Julius' mother was very protective of him, but it sometimes isolated him from other children

Although Julius was not permanently hidden at home like some intersex children, some of his earliest memories involve being kept away from others.

"Mostly it was the constant reminder by my parents to avoid certain modes of play because I could be harassed or abused.

"Also, my mother's strict protection of me meant I kept changing schools. It was a very isolating feeling, [and] it made it very difficult to make and sustain friendships at that early age."

His mother also took Julius to traditional herbalists, who tried to "cure" him. Inevitably, the treatments failed.

As a child, Julius was taken to herbalists seeking to "cure" him

"When I was 11, I had to study hard to get a place in an Anglican girls' boarding school," he says. "My mother thought it would be the safest place for me - but it was a real nightmare.

"Obviously, because of all the changes that come with adolescence, everything they [the girls] loved, talked about and did, I was not interested in, like plaiting hair, discussions about romance novels and body grooming.

"I was completely different in my outlook and likes and didn't feel the need to disguise it. That made it a nightmare to belong.

"And some of the girls started to look pretty to me, which was more than a nightmare to comprehend and contain, given I could not speak about it or act on it."

What is intersex?

Intersex people are born with a mixture of male and female sex characteristics.

To determine the sex of an intersex child doctors try to work out what happened during the baby's development.

They check the body's DNA containers, the chromosomes, to see whether the child is genetically female or male.

They see if the baby has ovaries or testes, and whether they have a womb or not.

They also test the hormones the body is producing and try to determine how the baby's genitals may develop.

Test results can be on a scale between male or female.

According to the United Nations, the condition affects up to 1.7% of the world's population.

Read more:

By the time Julius was 16, it was obvious he was becoming a man. His voice and hair were changing. He fitted in even less than before at a girls' school.

"I found myself at a crossroads," he says. "I had to leave the school."

Reaching adolescence, Julius's body changed and remaining at a girls' school became untenable

Visiting a doctor, he learned that he had a condition where his body "did not respond to the typical male hormones responsible for typical male body formation and that it was neither a disease nor witchcraft, just a biological condition".

"That information was a relief because then, having become born again, I changed my prayers from deliverance from demons to just healing of an otherwise common condition."

But with all the physical changes his body had undergone, he could not continue living as a girl.

Julius left Uganda to continue his studies in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi, where under guidance from his doctor he came to a decision.

"I made up my mind to discard the female image and start living as the man I was - albeit with all the ambiguity," he says.

"It was a hard change socially, especially because I was still young but it was also a relief."

Threats

When he returned to Uganda, it was no longer as Julia, but Julius.

At first, Julius pretended to be his "brother" but it wasn't long before people saw through the ruse, recognising him as the person who used to be called Julia.

One day, Julius says his story was leaked to a newspaper in Uganda: "Everybody wanted a piece of me. They wanted to dissect me."

A little later, a situation that might have been complicated or awkward became dangerous.

Someone told a newspaper about him and suddenly, without warning or consent, Julius's private journey became public.

"I received threats and a lot of harassing comments in the news," he says. "It is a very disturbing and frightening thing at that age to have everybody give opinions on what they think you are.

"You get to believe some of these things. Some of the comments alleged I had a sex change and people like me should be burnt.

"That scares a young person to death, and it scared me in ways hard to describe."

Julius credits his Christian faith - the feeling that, with God, he was not alone - for keeping him afloat at this time.

Julius found work in South Africa as a technical writer for a software company

But he had good reason to believe he was not safe in Uganda and left again, this time travelling to South Africa.

A friend helped him get a technical writing job with a software company, which paid well.

"This made it easy for me to be allowed to stay there and kept me psychologically safe for some years," he says.

Cheered on live TV

Then one day, flicking through the news, a story caught his attention. The Ugandan media were discussing an intersex boy.

Julius knew he had to do something.

"I was concerned," he says. "I decided to go back home to help him."

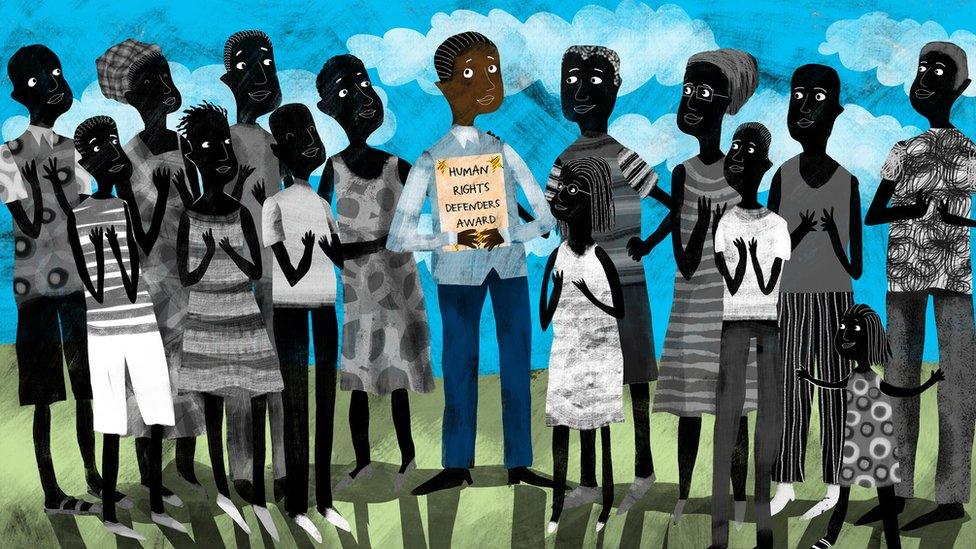

Julius received a standing ovation after returning to Uganda and telling his story to an audience on national TV

"For him and others like him, I faced my fears in front of a live audience on national TV, and I told my story."

When he had finished, the whole room stood and cheered.

It was another turn taken.

Repressive laws

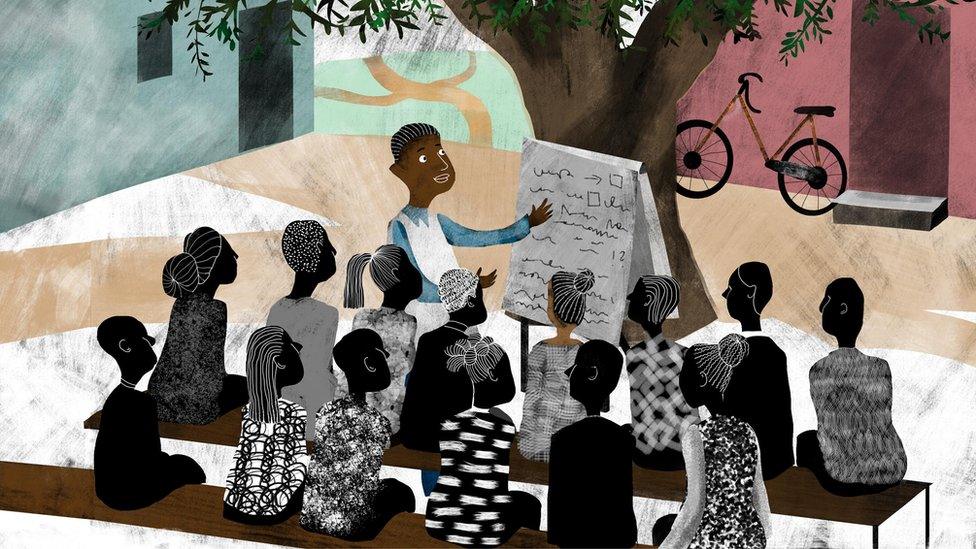

Now Julius, who is married with four children, works as a full-time educator in Uganda, as head of intersex health and rights organisation SIPD Uganda.

He educates and counsels people about intersex issues, working with community midwives to fight the stigma around intersex babies, advocating for policy change and building capacity and partnerships in the field.

He now works full-time as an educator on intersex issues

"The standard treatment of intersex conditions in Uganda is still, unfortunately, to try to normalise the child as much as possible," he says.

"This involves deafening silence and isolation and, in worst case scenarios, child murders of the intersex infant. There are also a lot of abandonments on rubbish heaps and in latrines."

The combination of traditional religious values, pop culture that defines what maleness and femaleness look like, and repressive laws that equate intersex identities with homosexuality ("and, in some instances, an intersex person can also be gay") create "an even more dangerous climate to operate in", he says.

As recently as 2014, Uganda tried to introduce a draconian anti-homosexuality law, which required homosexuals to be jailed for life. It was overturned, but had a chilling effect.

Despite this, and his own grim assessment, Julius believes his public education work, allied with more sympathetic media coverage, is beginning to shift attitudes.

Julius now has four children of his own.

His own thinking has also continued to develop.

"Certainly as I get older, I am now thinking about different kinds of safety, especially for the children and also blackmail that comes from people who feel the need to remind me that I once wore a skirt," he says.

"That said, I have developed greater resilience with age and even with threats still coming my way now and again, I have more control of my life and how to live it.

"Yes, I sometimes feel I can do better with this or other surgery or hormone treatments but it is something to contemplate in light of social expectations - not something I feel I must do to be a normal human being.

"There is nothing wrong with me and there is often nothing wrong with most intersex children or people."

The images in this article were produced for the Open Society Foundations by PositiveNegatives.

- Published24 January 2017

- Published22 April 2016

- Published11 October 2011

- Published10 November 2015

- Published8 August 2015

- Published1 August 2014

- Published10 February 2014