Letter from Africa: Sudan's rulers 'shirking action on cholera'

- Published

Refugee camps have been identified as the source of the cholera outbreak

In the latest of our series of letters from African journalists, Yousra Elbagir criticises the Sudanese government's failure to get to grips with a cholera outbreak.

After 10 months, Sudan's Ministry of Health finally confirmed that there have been 265 deaths and more than 16,000 infected cases of "acute watery diarrhoea" in 11 of the country's 18 states.

A half-admission that came only after the disease pierced the bubble of Sudan's capital, Khartoum.

Medical professionals have long diagnosed the cases as cholera, despite the euphemisms the government has insisted on to downplay the severity of the crisis.

But cholera by any other name is still cholera.

The Federal Minister of Health, Bahar Abu Garda, told parliament that cases of "watery diarrhoea" were not his business - shifting blame to the Ministry of Water Resources and State Ministers.

'Crumbling infrastructure'

The private hospital of Khartoum's State Minister of Health, Mamoun Himeda, has a printed sign on the door, refusing the admission of any cases of watery diarrhoea.

In April, journalist Ammar El-Daw was detained for reporting on the outbreak and accused of defamation by the minister of his home state, Gaderef.

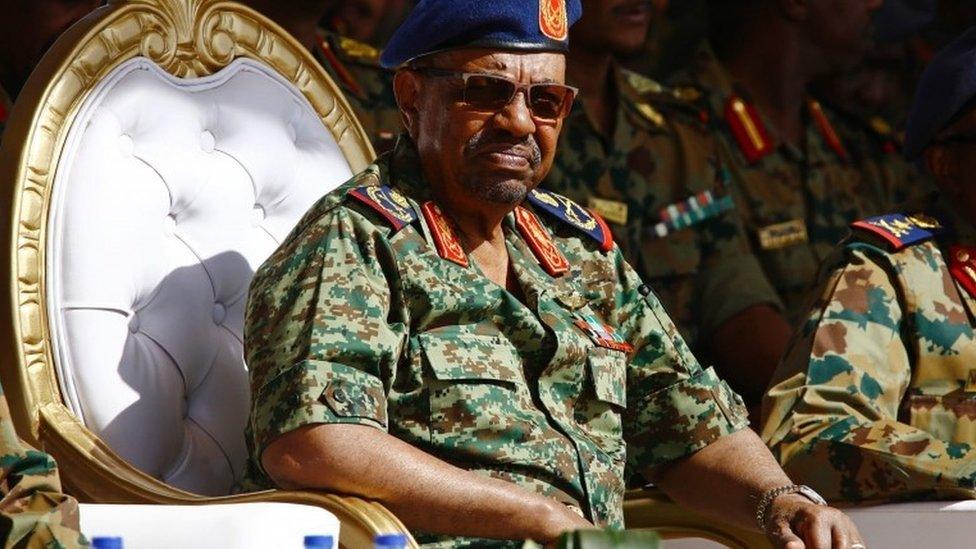

Some Sudanese have accused President Bashir's government of ignoring them

While the country's politicians continue to shirk responsibility and avoid action, the number of cases continues to climb.

The first infections were confirmed as early as August 2016, in the White Nile state where the cluster of South Sudanese refugee camps has been identified by the government as the source of the outbreak.

Whatever the origins, Sudan's crumbling infrastructure and underfunded healthcare system made conditions rife for the disease to spread. Poor sanitation, meagre emergency services and underpaid doctors, striking intermittently since October 2016, have left the nation extremely vulnerable.

Medics have highlighted the lack of quarantine spaces and photos have been shared online of brackish water pouring out of taps across the country.

Yousra Elbagir:

Once again, the Sudanese community must rely on itself to fulfil its basic needs.

Imams are spreading awareness at Friday sermons in mosques across the capital Khartoum, calling for the government to address the issue and praying to God to prevent a disaster.

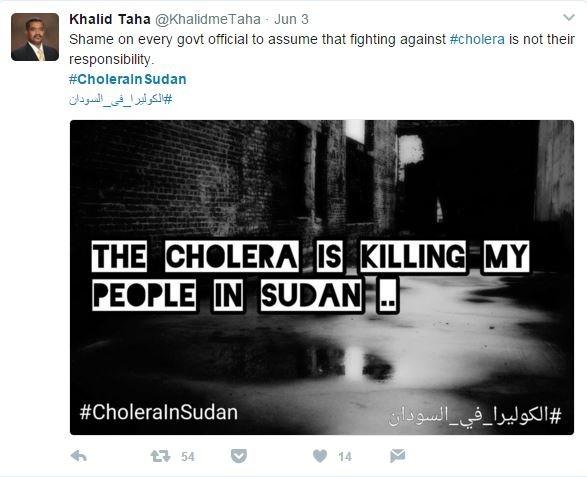

Citizens are handing out health and safety pamphlets throughout the capital and activists are taking to Twitter and Facebook to spread awareness and criticise the government's approach.

Trigger word

And protests have broken out at cemeteries after the mass burial of tens of bodies, all victims of cholera. Locals have organised two sit-ins in the White Nile state. All of which seems to have fallen on deaf ears.

The World Health Organization has been ominously silent in the face of the growing crisis. Many assume that pressure from the government - never shy to expel a UN official for saying the wrong thing - has left them at a loss for words.

In this case, "cholera" seems to be the trigger word.

Sudanese Twitter users have been using the hashtag #CholeraInSudan, hoping to attract international attention and pressurising the government to act - the same international pressure that forced the Sudanese government to restore subsidies on imported medicine back in November.

Once again, the Sudanese community must rely on itself to fulfil its basic needs.

More from Yousra Elbagir:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external