Setting Senegal's young footballers an educational example

- Published

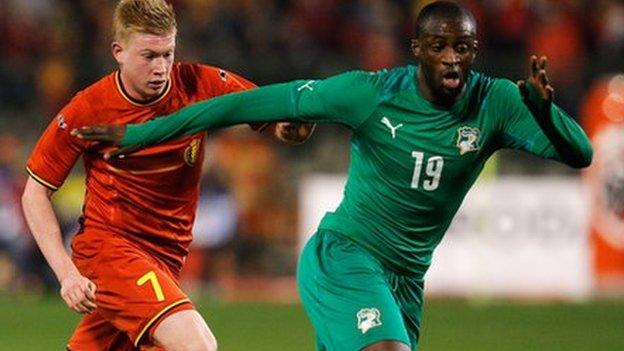

Being part of Diao's foundation is prestigious for young players because of its links

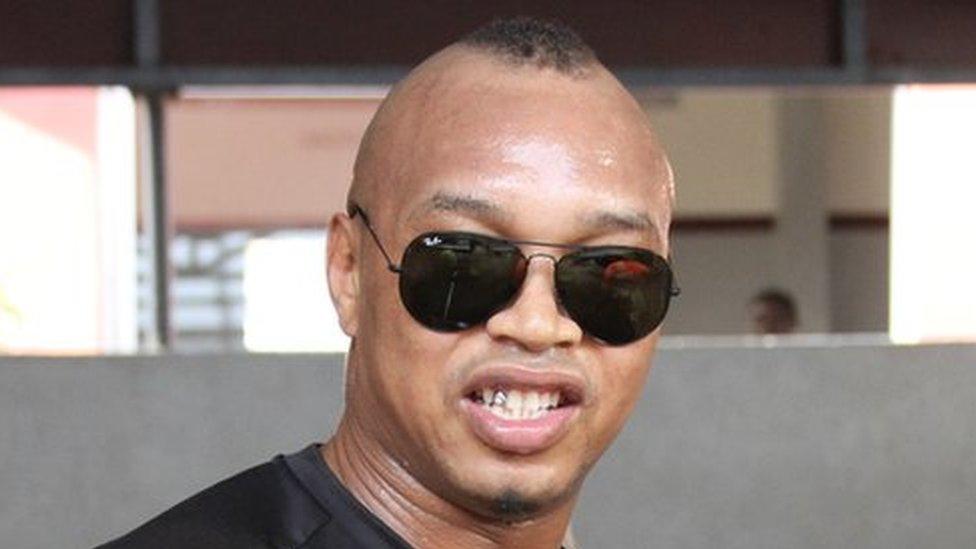

Salif Diao left his home town of Kédougou, in the south of Senegal, when he was only 13 to pursue his dream of becoming a professional footballer.

The journey took him to Dakar, the capital city of Senegal, where he sometimes slept outside the national stadium and washed plates for the guard soldiers to get something to eat.

It was a necessary part of the journey which finally led him to Liverpool, one of the world's biggest football clubs.

But his quest for a professional football career meant that he had to drop out of school.

Looking back at a career that has given him both fame and money, his only regret is that he had to trade his education for a professional football career.

"It has been a very hard and tough journey from when I was 13 years old, when I left my home town, up to when I finished my career," said Diao at his office in central Dakar.

Salif Diao had to sleep rough under a stadium while awaiting his football trial.

"I wanted to attend Prytanée Militaire which is one of the best schools, I would say in Senegal.

"I did not reach it but along the way while I was playing football, I carried on with my education."

Diao could not achieve his educational goals because of the demands of a professional football career.

No alternative to football

As result of this disappointment, Diao set up his Salif Diao Foundation - Sport 4 Charity three years ago. The foundation aims to produce educated footballers.

He counts himself lucky to have gone on to make a successful football career.

His friends were not as lucky. Those who couldn't make it in football were asked to leave the FC Metz Academy in Dakar where his career started.

This, he says, meant they had to lead difficult lives because they did not have an education to fall back on.

Salif Diao, who retired in 2012, spent five years at Liverpool

Diao's academy works in different areas of Senegal. I visited two of them in Dakar.

On any given day there are dozens of children going through their paces.

The training sessions take place late in the afternoon after school.

Many of them take their prayers first and go through inspections with the coach/educators before training starts.

No school, no football

These regular inspections are meant to ensure the young footballers are attending school, which is the biggest requirement for enrolment.

At another location, the students play football next to a vocational training centre.

Here they are taught subjects such as metal-work and furniture making. Those who don't get the required mark or attend school at the centre have no place on the football field.

"I always liked education because today here we are, my career is finished. If I don't have a good education, what will I be doing?" he asked.

For many, football coaches have replaced teachers as role models

Although football has given him all the comforts in life, he feels the only way he can give back to his community is by encouraging young footballers to have something to fall back on in hard times.

"If you don't have a basic education in this life, it's hard, it's tough and as we know especially in Africa, out of 1,000 players, maybe one would become a professional footballer."

A 2014 report by the Professional Footballers' Association (PFA) estimates that about 700 players are released by their clubs every year in UK.

It says of those who enrol at academies aged 16, half of them will be out of the game after two years, while 75% of those who remain will be out by the age of 21.

So to enrol at his foundation, which occasionally gets support from his former clubs Liverpool and Stoke City, one has to be in school first.

Steven Gerrard's boots

There are several football academies in Senegal, most of which are focused more on developing football careers but for Diao a school report or attendance register is a pre-requisite for enrolment.

"The purpose of our academy is not for business like other academies. We are using the game as a carrot to keep the children in school. Eighty percent of what we do is education and 20% sport.

"If they fail to attend school or attain the required academic rate, they don't train with us.

"We have a tool which is football. If you see everything happening around this ball, it's so massive but I think we are not capitalising on a maximum level especially in terms of education," said Diao.

Salif Diao: 'Made to feel unwelcome' when he arrived at Liverpool

With young Senegalese players such as Sadio Mane and Idrissa Gana Gaye now enjoying successful careers in the game having worked their way out of a tough life, it will be tough for Diao to convince the aspiring footballers but he feels education should come first.

"They love the game, they want to be famous and they want to be financially free.

"When I was a kid, the [role] model we had was a school teacher but now I think the football coaches or educators have replaced the teachers.

"They have that tool which is the ball and can tell these kids that they need to go to school," said Diao.

"Other academies focus on putting maximum effort into building facilities and having coaches that can produce the best footballers. We don't talk of coaches, we talk of educators."

Diao believes he has a worthy incentive for the young footballers. Being part of the foundation comes with a lot of prestige.

You have access to the same football kits worn by children enrolled at the Liverpool and Stoke City academies in England.

The football boots are donated by Diao's former Liverpool teammates such as Steven Gerrard. Some even come with his signature. To the aspiring footballers this is huge.

This is the second in this week's Where Are They Now? series by Stanley Kwenda, looking at what some of Africa's ex-football stars are doing after hanging up their boots. He will also speak to Peter Ndlovu, Benni McCarthy and Nwankwo Kanu.

Read more:

- Attribution

- Published2 June 2017

- Published26 June 2017

- Published14 June 2014