Can jobs in Ethiopia keep Eritrean refugees out of Europe?

- Published

Some 30% of the new jobs will be reserved for refugees

Many thousands of Eritreans have fled the country for Europe in search for a better life. A multinational initiative is now trying to stem the flow of migrants to Europe by training refugees and giving them jobs in neighbouring Ethiopia.

"I was not sure we would make it across. I am so relieved we are here," says 19-year-old Salama - not his real name.

Together with his friend Abiro, they have been walking for two days from Eritrea, without any food or water. At one point, they claim to have been shot at by government soldiers who are stationed along the heavily militarised border between Ethiopia and Eritrea.

"The reason for fleeing from our country is because the Eritrean government keeps on forcing us to join the national service and we are wanted in our homeland.

"We walked through the bushes hiding not to be seen by the Eritrean soldiers and we were able to escape," says Salama, the more talkative of the two.

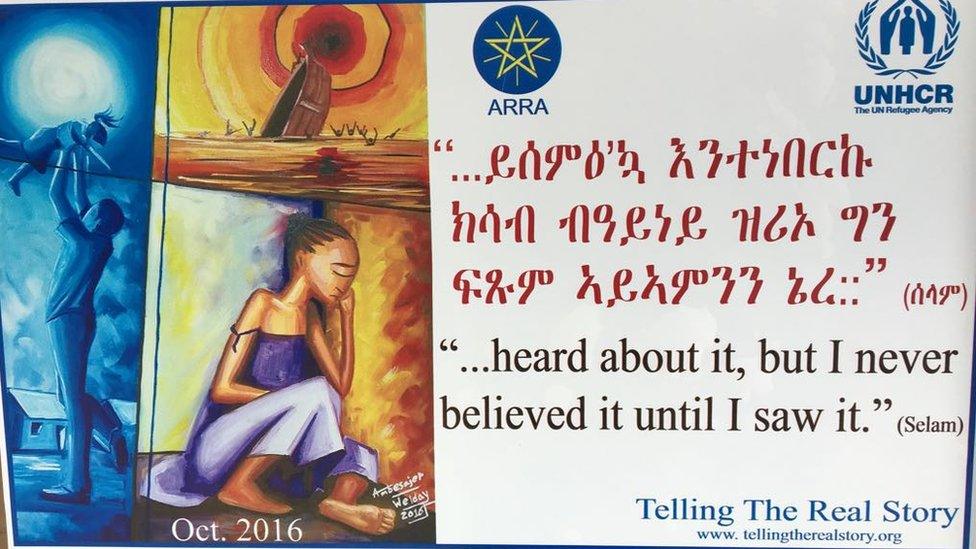

The UN has launched a campaign to warn people about the dangers of trying to get to Europe

Recent weeks have seen hundreds of Eritreans arrive at refugee camps and reception centres along Ethiopia's northern border.

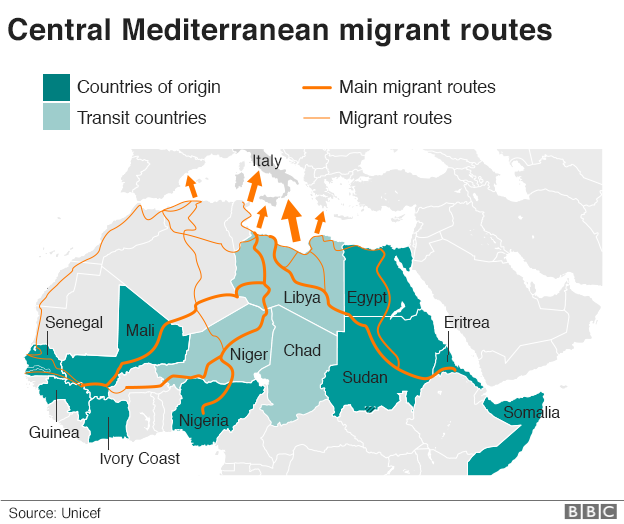

Many of those who reach Ethiopia intend to move on to Sudan and then Libya, hoping to eventually get to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea but some end up settling in Ethiopia.

It's a risky journey that involves thousands of dollars and an intricate network of smugglers.

More than 2,000 people have died so far this year trying to make the crossing.

"I am not sure where we will go from here. It's our first time out of Eritrea. Maybe we can settle here and get jobs," says Abiro, speaking in his mother tongue Kunama.

"If not, we will move as far away as possible. Maybe Europe."

Through the translator, I ask them what they know about Europe and they shake their heads, indicating they know nothing.

Eritreans make up the seventh largest group of people who arrive in Europe each year seeking asylum, according to the UN, even though the total population is less than 6 million.

A high proportion of African migrants trying to reach Europe are from Eritrea

But the government in Eritrea has dismissed such figures and says that people from other countries are posing as Eritrean refugees.

Information Minister Yemane Gebre Meskel told the BBC that the number of Eritrean refugees leaving the country was much lower.

"The numbers of Eritreans leaving the country is much inflated; by most accounts 40 to 60% are from Ethiopia and/or other countries in the Horn."

Donors and the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) are trying to dissuade young people like Salama and Abiro from making that journey by creating jobs for refugees in Ethiopia as part of a multinational deal.

The UK, European Union (EU) and the World Bank have already invested $500m (£400m) into the programme.

According to the plan, the industrial parks will be set up in the towns of Mekelle, Jimma and Ziway, creating more than 100,000 jobs.

Some 30,000 of the jobs will be reserved for refugees. Ethiopia hosts nearly 800,000 refugees, mainly from Eritrea, Somalia and South Sudan.

"This becomes even more important in a country like Ethiopia, where most of the refugees are dreaming to continue onward and the reason they give is that they don't see their future here and don't know what to do," says UNHCR regional head Fafa Attidzah.

At the refugee camps, authorities are already preparing for the job opportunities by training refugees in areas such as masonry, carpentry, cookery and sewing. There are also computer classes for some of the younger inhabitants.

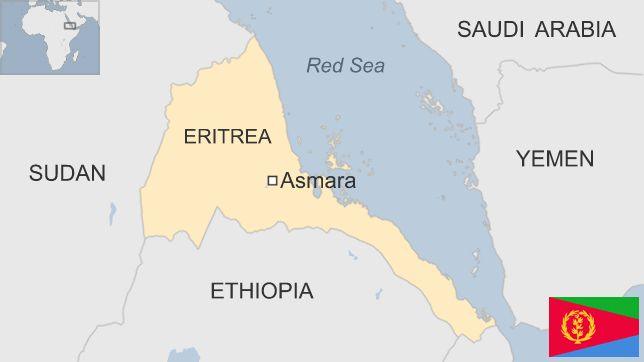

Eritrea at a glance:

Gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993 but relations remain tense

Opposition parties and private media banned

Conscription can last for decades, human rights groups say

One of largest countries of origins for Africa refugees arriving in Europe

Government says problems exaggerated and blames problems on Western backers of Ethiopia

The UN has started a programme to make sure more people are warned about the dangers of making the journey.

Eritrea says its tense relations with neighbouring Ethiopia are behind its system of national conscription, which can last for decades.

Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993 after a long civil war and the two countries then fought a 1998-2000 border war that left an estimated 80,000 dead.

Eritrea has also dismissed the job creation programme, with the information minister calling it "ludicrous... with a sinister political agenda".

"What we need is peace and for Ethiopia to respect international decisions [meaning the decision to award Eritrea the disputed border town of Badme]."

Eritrea's government says the number of refugees has been inflated and that many are actually Ethiopians

But will jobs in Ethiopia be enough to stop the movement of refugees?

Teklemariam, who has twice attempted to get to Europe and failed, tells me much more needs to be done in refugee host countries to sway those who want to move to Europe.

"I try to tell them that it is not safe trying that journey. Sometimes they listen to me, sometimes they don't, but training like this is good, because if they learn some trade, maybe they will stay."

Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn says such programmes are not just important for refugees but also for millions of young unemployed people in his country.

"We have to address this issue critically because we understand our situation well and that's why we are investing resources in making sure our children are safe, and can make a living."

While many refugees here are happy at the prospects of getting jobs and restarting their lives in a foreign land, many more remain unconvinced, and are determined to risk everything for a chance at a better life in Europe.

- Published20 June 2017

- Published8 June 2016

- Published14 July 2016

- Published9 November 2015

- Published18 April 2023