'Nigeria treats us like slaves' - but is Biafra the answer?

- Published

It is 50 years since Nigeria's brutal civil war calling for the secession of Biafra started. By the time it ended in 1970 over one million people had perished. Now a new movement has emerged calling for independence. The BBC's Tomi Oladipo and Stephanie Hegarty explore its popularity.

Hidden high in the luscious, green hills of Enugu in south-east Nigeria, down a beaten track - under a sign that says leprosy colony - is the Biafran war veterans' camp.

Like its location, residents there are verging on obscurity.

Four old men sitting on parallel wooden benches, propped up on metal crutches - swaying and chanting along to an old battle song.

They fought and were crippled in the bloody Biafran war.

"We went to that war with nothing, we went empty-handed," says Francis Njoku. "Some held machetes, some had sticks. They [Nigerian forces] had machine guns."

Mr Njoku, now 69, lost his kneecap in a gun battle.

It was a desperate fight for survival. But it ended in a ceasefire and Biafra became part of Nigeria again.

Biafran War veterans remember the conflict 50 years on

At the end of the war, the Nigerian head of state General Yakubu Gowon declared there was "no victor, no vanquished" - this became the motto of reunification.

But for many people in the south-east, the reunion has been an uneasy one.

"If you come to Igbo-land you can see there is no development here," says Mr Njoku.

It's a common perception we heard many times here - that Igbo people are marginalised in a Nigeria that only serves the interests of the two other main ethnic groups - the Hausa and Yoruba.

Although government statistics, external show that poverty rates are far higher in the north than other regions, there are some genuine complaints.

In almost 30 years of democracy, Nigeria hasn't had an Igbo president.

"We still need [Biafra]," says Mr Njoku. "Nigerians are maltreating us - like slaves."

The Biafran war explained

It's a strong sentiment and one that a new crop of activists is playing on. Among them a new leader has emerged.

Despite bail conditions saying he cannot speak to the press, Nnamdi Kanu agreed to our request for an interview.

We were to meet in his father's compound in the south-eastern town of Umuahia - the last bastion of the Biafran state before its surrender.

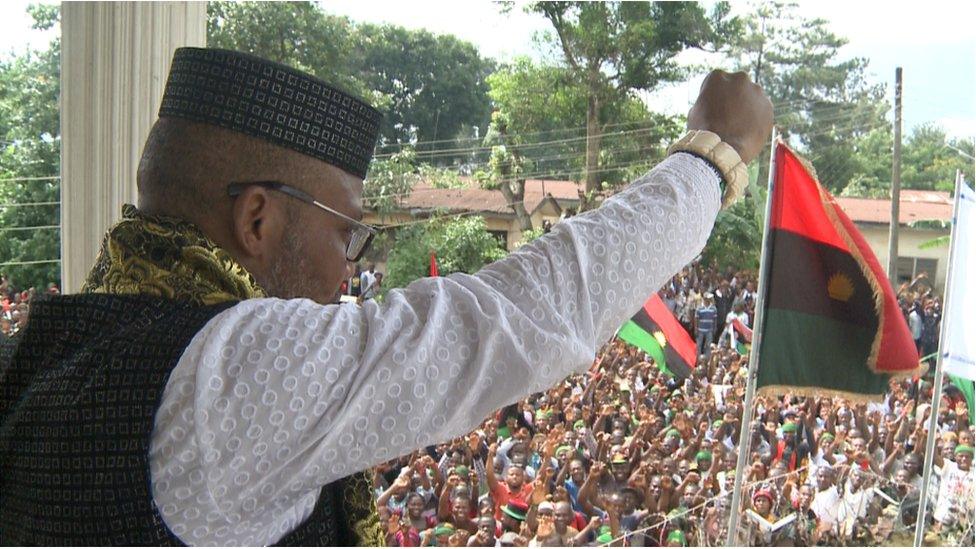

As we approached Umuahia, we were greeted by a large crowd that had seemingly been organised for our benefit.

We had arranged the interview the afternoon before and in that time he had gathered up to 1,000 people - they surrounded his father's compound waving huge striped flags, carrying the Biafran symbol of a half-rising sun, and foghorns - chanting their support under the pouring rain.

Senior government and police officials live a few hundred metres away but no attention was paid to their presence.

The cheers escalated to roars as they spotted Mr Kanu emerge onto the balcony of the house with his fists raised.

He has gold and black cloth wrapped around his shoulders and a matching gold cap on his black suede designer loafers. "They're calling for Biafra," he says softly, with a smile.

All of this for a cause that has him facing treason-related charges in court.

"Basic human development, basic economic development, basic social development, can no longer be attained for the simple reason that there exists in the polity mutual suspicion, mutual hatred, mutual resentment," he says.

"So the best thing to do is to separate."

Biafra at a glance:

Ipob claims these existing states would make up an independent Biafra

First republic of Biafra was declared by Nigerian military officer Odumegwu-Ojukwu in 1967

He led his mainly ethnic Igbo forces into a deadly three-year civil war that ended in 1970

More than one million people lost their lives, mostly because of hunger

Decades after Biafra uprising was quelled by the military, secessionist groups have attracted the support of many young people

They feel Nigeria's central government is not investing in the region

But the government says their complaints are not particular to the south-east

Mr Kanu is calling for Biafran independence through a referendum.

"We just want to control our political destiny so we can build factories, [build] our roads, cities, bridges, not having to depend on somebody in [the capital city] Abuja."

The Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob) movement that he leads believes an independent region will resolve the issue of the marginalization of the Igbos but they also want to bring the non-Igbo, oil-rich Niger Delta into the breakaway state.

They insist it was part of the original Biafra.

"Should any other part of Nigeria wish to join Biafra they are welcome to do so, as long as they are Judeo-Christian... the value system that underpins Biafra."

The movement for Biafra clearly has significant influence around the south-east of Nigeria.

Biafra war veteran Francis Njoku: "Nigerians are maltreating us - like slaves"

A recent stay-at-home protest ordered by Ipob was heeded in many towns. However it seems from many people we spoke to in the region that while they support the idea of Biafra, they are not clear as to where it may take them.

The generation that witnessed the war insists on pacifism, as the men at the veterans' camp told us.

"We are talking about dialogue, not by fighting," said Mr Njoku.

Some are profoundly afraid of where the current rhetoric could lead.

Reverend Moses Iloh is an Igbo but he grew up in the north and now lives in the south-western commercial hub of Lagos.

When the war broke out, he moved to the Biafran Republic to work with the Red Cross.

"The war was one of the crudest you can find," he recalls. "Sometimes there would be more than 50 or 100 children - you would dig a big trench and pour their dead bodies in. I was there. I am not telling you a lie. The suffering was so bad."

Like many Igbos, he supports their ethnic solidarity but sternly warns that any attempts to secede again would be catastrophic.

"Nigerians will not let them go, they will slaughter them - and the whole world will turn their heads and say it's an internal affair."

Igbo politicians have rejected calls for Biafra

In response to the recent pro-Biafra agitation, a group in northern Nigeria issued a threat, giving all Igbos in the region three months to leave.

The move received widespread condemnation, even in the north, but reflected the delicate nature of Nigeria, a country created when hundreds of different ethnic groups were brought together by the British colonial powers.

While the Igbos comprise one of the three largest ethnic groups, they have fewer states than the Hausas in the north and the Yorubas in the south-west, and subsequently get a smaller budget allocation.

This, some feel, puts them behind the other regions. The south-east has not been at the forefront of Nigeria's development and none of its cities are major economic hubs.

Path of uncertainty?

Over the years the Nigerian government has always ruled out the possibility of the country's fragmentation. Acting President Yemi Osinbajo recently addressed the Biafra issue:

"Clearly our strength is in our diversity, that we are greater together than apart," he said. "Brotherhood across tribes and faiths is possible".

Top Igbo politicians recently rejected calls for Biafra but stressed the need for fairness and equality.

Though for some, these leaders are the problem, entrenched in the corruption that plagues Nigerian politics.

Mr Kanu has called on his followers to boycott upcoming local and national elections.

The people of the south-east are left with a choice: Stick with their current leaders - and Nigeria - or choose a much less certain path.

- Published10 June 2016

- Published30 November 2015