Madagascar: Where France's maritime history sails on

- Published

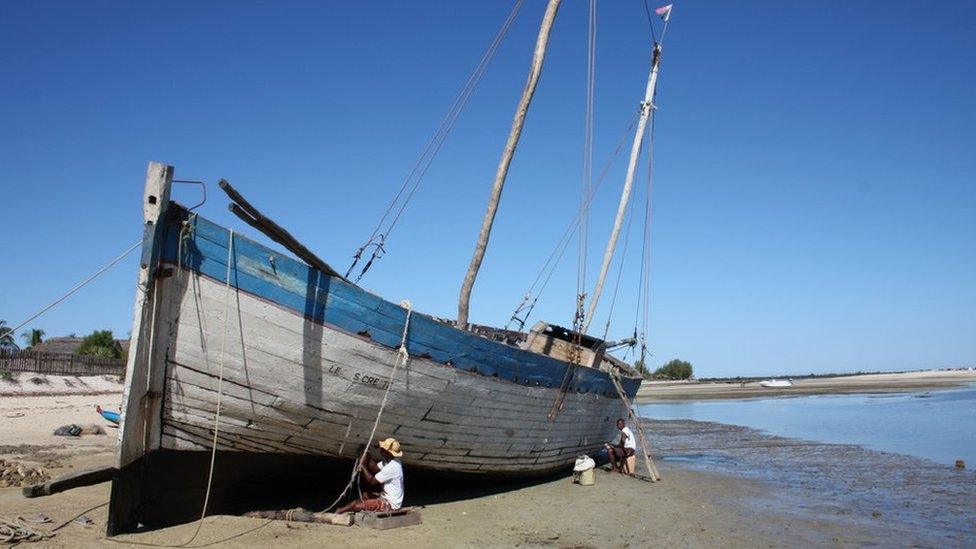

Schooners typically have two or three masts with multiple sails

Madagascar's master shipbuilders can all trace their skills back to just one family who arrived on the African island more than 150 years ago, writes Tim Healy in the capital, Antananarivo.

In the 19th Century, schooners were a familiar sight along France's northern coast, their majestic sails fluttering in the wind. Nowadays, they have been replaced by boats which are far faster, more efficient - and less romantic.

But there is still a corner of the world where a new generation of carpenters is keeping old maritime traditions alive by crafting these vessels to original standards.

By royal appointment

The mastery shown by carpenters working in the town of Belo-sur-mer on Madagascar's west coast is respected around the world - at least one of their beautifully crafted schooners has been sent to collectors in France in recent years.

And it is all thanks to one family, brought to the island by a king's ambition.

Malagasy schooners require regular maintenance

It was King Radama II of Madagascar who decided to bring the schooner to his East African island.

For more than a thousand years, Arab boats moved along the coast of Madagascar trading goods for slaves. They were joined in the 17th Century by European trading vessels. Until the 19th Century, the Malagasy fleet was composed of mainly smaller fishing boats and canoes.

But the Vezo Sakalava - coastal people from the western region - wanted to develop bigger trading boats to move cargo around the island, and King Radama was happy to grant their wish.

The king turned to the French government, asking them to send shipwrights to teach his people.

The Justins, a father-and-son team of carpenters, set to work restoring one of their schooners

Soon, the Joachim family, who were creoles of mixed European and African descent, and fellow marine carpenters from France's neighbouring island of La Reunion were sailing to Madagascar.

But when the family arrived, they discovered that the king had been assassinated. His reign had lasted less than two years, from 1861 to 1863.

Poetic names

The Joachims soon found themselves forced to flee to the east coast and, over the course of several decades, the family circumnavigated and lived in parts of southern Madagascar, eventually settling in the western port of Morondava.

It was here, and in nearby Belo-sur-mer, that Enasse Joachim and his three sons began practicing their craft, building schooners for Madagascar.

Of Dutch origin, the ships can have two or three masts decorated with several sails, and reach up to 22m (72ft) in length. As the vessel does not have a keel, it is ideal for navigating shallow Malagasy lagoons and mooring on sandbanks and beaches.

The tradition of building ships runs through families

By 1904 - some 40 years after they first stepped foot on Madagascar - some of the Joachim family had managed to establish shipbuilding schools. It was done with the approval of France's Governor Gallieni, since the French had colonised Madagascar almost a decade earlier, in 1895.

The Malagasy apprentices of the Joachims became master carpenters and shipbuilders in their own right and passed down their skills through several generations, turning Belo-sur-mer into a major shipyard for Schooners, or Botsy in Malagasy.

More than a century later, their legacy continues in Belo-sur-mer, carried on by families like the Justins, who have built two ships.

"My sons and I come from a long line of shipbuilders going back to my great-grandparents," says the patriarch, known simply as Mr Justin.

Traders have used boats to ferry cargo around Madagascar for centuries

The name of one of their boats, Fagnanarantsoandraza, translates from poetic Malagasy to "let it be known that the fine have no need to stay here". It is a name worthy of the love put into building the boat, constructed with timber painstakingly collected from nearby forests.

The vessel, launched in 2012, is 18m in length and can carry loads of up to 50 tonnes, usually salt or agricultural products, to areas that are often inaccessible by road.

The ships are summoned home for regular maintenance, including the resealing of their hulls, before returning to sea.

Schooner on a tomb

Of the three Joachim sons, Albert's influence is perhaps most felt today. The Malagasy diminutive of Albert is Bebe, and the port in Morondava bears this name.

While descendants of Albert and Fernand Joachim are believed to live on in Morondava, less was known about their brother, Ludovic, until recently.

He had married a woman 54km (34 miles) away in the village Belo-sur-mer, where he died in 1902. A century later in 2002, a French woman living locally was determined to locate Ludovic's grave and managed to do so with the help of the mayor, and village elders.

Discovered 400m from the village where it was hidden by undergrowth, the modest grave was marked out with a mound of rocks and a fading wooden cross etched with his name.

Local authorities decided to restore the grave and mounted a miniature wooden schooner upon the tomb, to honour the Joachim family's unique contribution to the island's seafaring traditions.

One of the original shipbuilders, Ludovic Emmanuel Joachim, died in Belo-sur-mer in 1902

- Published4 July 2017

- Published18 November 2016

- Published2 April 2017

- Published23 March 2017