Al-Qaeda hostages McGown and Gustafsson talk of time in Sahara

- Published

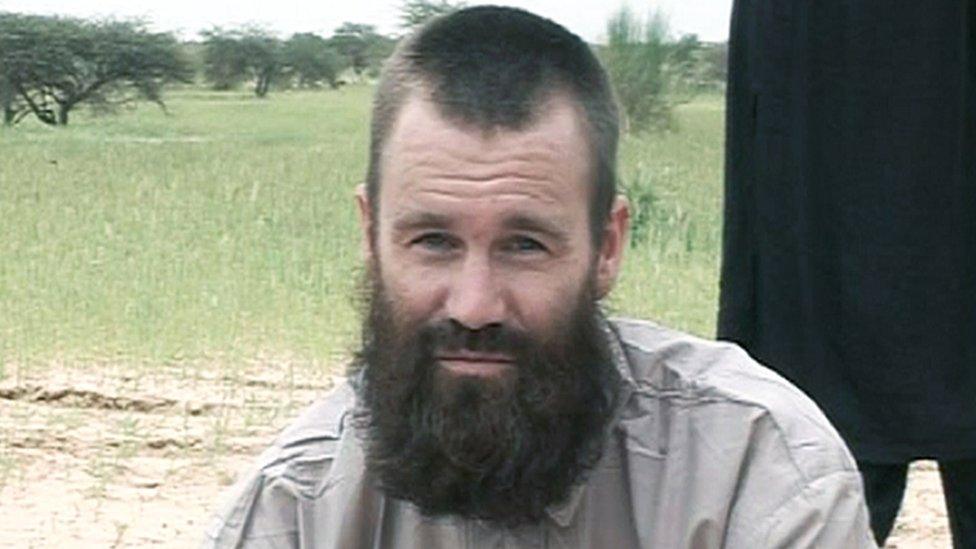

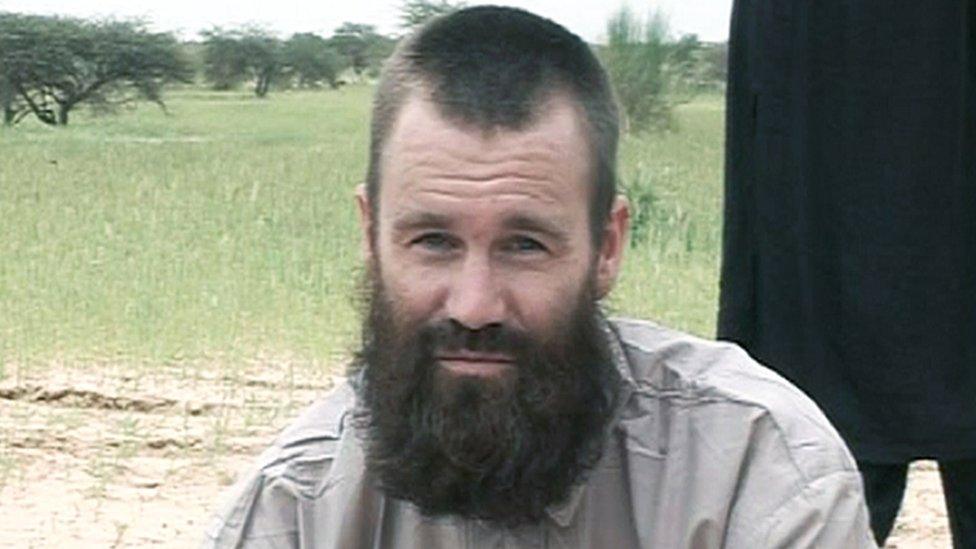

Stephen McGown said he thought his release was a "joke"

Stephen McGown watched the swallows migrate back and forth across the Sahara six times before he was finally rescued from the grip of Islamist extremists.

In that time, he only truly feared for his life on three occasions - all of them within the first panicked months which followed his kidnap from a hotel in Timbuktu.

Each time, the feeling was the same.

"Your brain takes you to another place and the seconds are long and you are numb," he recalled, speaking at a press conference in South Africa, thousands of miles from the men who had stolen six years of his life - and with it, the chance to say a final goodbye to his mother.

Mr McGown's rescue was the end of a hostage ordeal which has stretched not only across the years, but across continents. He was the last of the three men taken by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) to be released.

The 42-year-old had already watched his fellow hostages, Dutchman Sjaak Rijke and Swede Johan Gustafsson, leave the makeshift camps which had been both their home and prison.

Sitting in front of the media in South Africa on Thursday, Mr McGown admitted he had barely dared hoped he might be next.

"In the end, you just do not want to believe," he said. "Well, you want to believe, but you are tired of coming down with a bang."

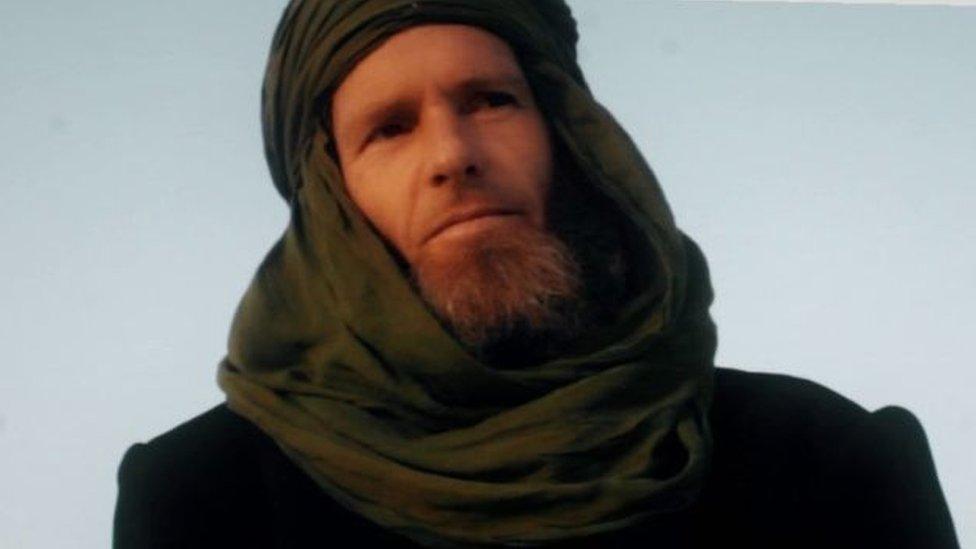

Johan Gustafsson (left) and Mr McGown were held for almost six years

A lot has happened since 25 November, 2011, the day AQIM stormed a small Timbuktu hotel and seized the three men, shooting dead a fourth man - a German - before driving them deep into the desert.

None of the men knew if they would survive. Mr McGown was perhaps the most vulnerable: his dual British-South African citizenship meant he was a prize bargaining chip.

Sitting and watching his captors slaughter a goat in the middle of the camp just days into the kidnap, he said he had thought soberly: "I am probably the first to go because of my British ties."

But he added: "I don't believe they knew my nationality. It would have been first prize for them if I was British. They kidnapped me just because I was non-Muslim."

Surviving

The first year was the hardest.

In the beginning, they were kept chained at night, huddled under a blanket together "like sardines" until someone unlocked them in the morning. Blindfolds were also used.

But eventually, their captors relaxed - even telling them they were "fortunate" to have been kidnapped.

"This is better than being in jail," Mr McGown recalled them saying. It was not, he told reporters, a sentiment he and his fellow captors could understand.

Johan Gustafsson explains why ransoms should not be paid

Then there was the Sahara itself: the boiling sun, the vicious thunderstorms and freezing nights.

"You have to learn how to find shade and endure the cold at night," Mr Gustafsson told a press conference [in Swedish, external] in his home country just hours before Mr McGown spoke.

"One has to learn to live with extremely little water."

Belief

Both men revealed they had converted to Islam during their time in the desert. Their reasons, however, were different.

"Before the desert, I was a Christian," Mr McGown explained to reporters. "They did not force me. I entered (Islam) of my own accord."

Whether he would return to Christianity was unclear - he needed to read more, he said, but he added: "I see many good things in Islam. It requires a very good character, a very strict character."

Mr Gustafsson converted for less spiritual reasons.

Mr Gustafsson was said to be "happy" and "overwhelmed" following his release

"That was the only thing I could think of that would buy me some time, even though I did not have much hope that it would work," The Local , externalreported him as saying.

"I didn't know anything about Islam, so I'm not sure how believable it was. But I think they saw it as their duty to accept it, even though I have a hard time believing that they actually believed me."

He never lost sight of their captors as the enemy, he said, even while eating and praying alongside them.

Freedom

After the first year, Mr Gustafsson, 42, tried to escape. For two days and nights, he was on the run from his captors.

When they eventually caught up with him, there was, he admitted, a feeling of relief.

"At the same time, it was a big disappointment, and I was afraid that at worst they would kill me," he said.

It would take another three years until one of the hostages was eventually rescued. Mr Rijke was discovered by French special forces during a dawn raid in April 2015.

Mr Gustafsson and Mr McGown were still being held, however. By now, they weren't being treated badly: three meals a day, medicine when needed, and an exercise routine - although that could be stopped by their captors at any point.

At times there was a radio, which meant they could catch some of news from the outside world through BBC Africa.

But the fact remained they were captives, with no end to their imprisonment in sight.

Mr McGown, pictured with his father in Johannesburg, 10 days after being released

"I cannot say you do keep going day by day," Mr McGown said. "Sometimes you sleep a lot, sometimes you do not eat much, sometimes you are absolutely miserable and want to fight with everybody."

But he kept himself going by focusing on those who were waiting for him at home.

"I did my best to see the best in a bad situation," he said. "I did not want to come out an angry person: the last thing I wanted to do was come out and be a bigger burden for my family."

Then in June, Mr Gustafsson was released into the waiting arms of Swedish police officers with "tears in their eyes".

Mr McGown was alone with his captors for another month before he was released. At first, he thought it was a joke.

Back home, recovering from a fever, he is adjusting to life back with his family and friends - although "so much has changed".

He is determined to come out of the experience a stronger person, and, in public at least, it seems it is only the death of his mother Beverly - which he learnt of the day he was rescued - he is struggling to come to terms with.

"It is the one thing I am unable to understand. All the other things I can try and find a positive in," before quietly adding: "But I am sure there is a positive..."

- Published26 June 2017

- Published3 August 2017

- Published2 July 2017

- Published6 April 2015

- Published19 May 2017