Eritrean priest in Italy denies 'people smuggling'

- Published

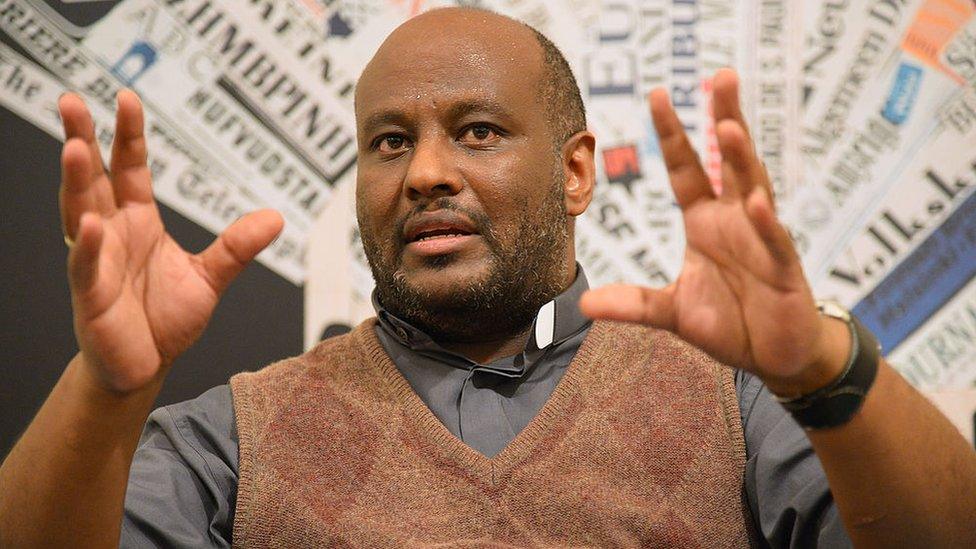

Eritrean-born priest Don Mussie Zeraj says better leadership is needed in Africa

A Catholic priest under investigation for people smuggling has told the BBC that politicians are trying to criminalise people helping refugees.

Don Mussie Zerai has lived in Italy for more than 25 years, since fleeing Eritrea as a teenager.

He says he regularly receives calls from distressed migrants making the crossing from Africa to Italy.

Mr Zerai was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015 for helping save lives by simply answering his phone.

But the prosecutor's office in the Sicilian town of Trapani is investigating him, along with others, over allegations of aiding and abetting illegal immigration.

He denies the allegation.

"When I receive a distress call [from people coming to Europe] I collect information and I pass the information to the Italian coastguard (which takes the lead in co-ordinating rescues) so the authorities can intervene," he told BBC Newsday.

Mr Zerai, 40, says he sends the same information to various non-governmental organisations, including Medecins Sans Frontieres and Migrant Offshore Aid Station.

But he denies he has been working with German NGO Jugend Rettet, which is accused of having direct contact with traffickers in Libya.

The Iuventa, a boat operated by Jugend Rettet, was impounded on the Italian island of Lampedusa earlier this month.

"The newspapers claim that [I] have secret chat, all this parallel communication - all this is false. My communication is clear, open and legal," Mr Zerai told the BBC.

'Public hostility'

He believes the accusations are part of a political campaign drawn up by Italian authorities, who have accused many charities of working with smugglers to act as a taxi service for refugees and migrants.

"If some NGOs are involved and do something illegal, it is correct to ask them for accountability but politicians are using campaigns to criminalise others. The consequence of this is, those who pay the price are the people who are in need."

Organisations involved in rescue operations have rejected accusations of collusion, saying their only concern is to save lives.

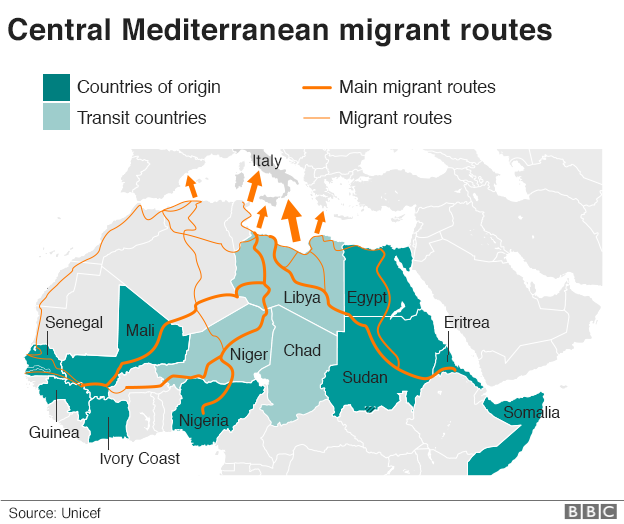

Thousands attempt the risky crossing to Italy each year

Italy is the main route for refugees and migrants trying to reach Europe due to its proximity to Libya, with many fleeing war, poverty or persecution.

Over the years the number of people coming to Italy due to the migration crisis has increased, and so has the public hostility.

Mr Zerai says he makes this clear to those back home.

"I tell them stay at home and that the atmosphere in Europe is not good, you are not welcome here at this time because of the economic crisis and discrimination.

"They say yes we know, but what's the alternative?"

'Dignified life'

Almost 1,000 people are thought to have drowned in waters between Libya and Italy this year, according to the UN refugee agency.

Mr Zerai believes the key to tackling the crisis is better leadership across Africa.

"It's not easy to say stay at home if no-one gives them a chance for a better life and a dignified life, so we need to invest resources and money to create these conditions," he says.

His comments echo those of Italy's ambassador to the European Union, Maurizio Massari, who told the BBC that the only way to tackle the crisis is to have stable African countries.

But Mr Zerai said this could take more than 30 years.

As a refugee, he cannot return to Eritrea because it is a "dictatorship", he said.

"I have denounced it many times so I'm at risk. But not all Eritreans have the same problem," Mr Zeria added.

Listen to the full exclusive interview with Don Mussie Zerai on Newsday on the BBC World Service on Thursday 17 August

- Published23 April 2017

- Published27 July 2017

- Published2 August 2017

- Published4 October 2016