Can Niger break out of its cycle of poverty?

- Published

Africa's population is expected to double by 2050, but in the country with the highest birth rate in the world it's on track to triple.

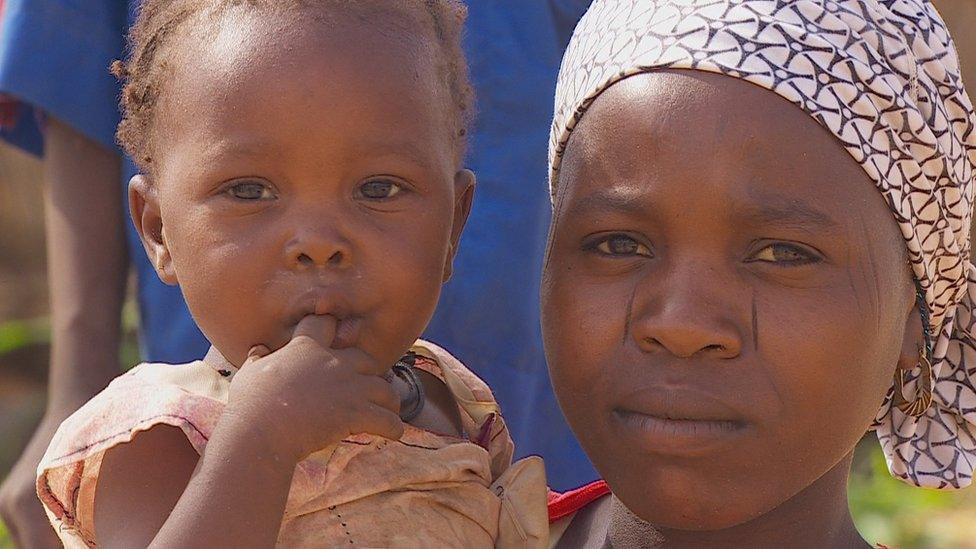

In Niger, women have an average of 7.6 children each - and in rural Zinder the rate is even higher.

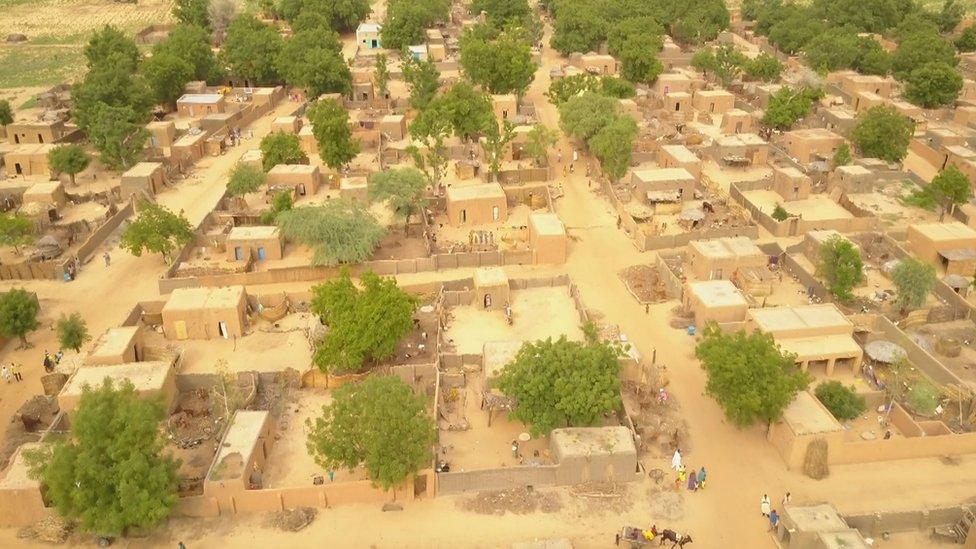

Not surprisingly it's more than just a statistic in almost every village you visit - there are kids everywhere.

Even the children have children - more than half the girls are married before the age of 15.

As economies grow and both countries and their people get richer, the number of babies being born naturally begins to fall, but Niger is also one of the world's poorest countries.

"In Niger, we have a national characteristic which is pro-birth where having children is considered a traditional sign of wealth and power," said Dr Hassane Atamo, head of the government's family planning division.

"The immediate consequences of having such a high birth rate is that it's impossible to feed, educate and care for all these children in the short term.

In Niger's 'husband schools', key issues of the day are discussed

"In the long term, the very survival of the country is threatened unless we take this window of opportunity to make the most of this youth dividend."

Most of the economy is in agriculture - subsistence agriculture - and barring a dramatic transformation it's an opportunity that may not be taken.

And so in the village of Angoual Gao they're getting plenty of outside help to try to encourage better family planning.

Tucked away amid the thick mud-walled compounds a group of young women are sitting having very frank conversations about contraception, forced marriage, or the problems of marrying young and having children early.

It's what the aid workers call "a safe space" for girls - and some of them are as young as 10.

Saratou Kanana, 27, is one of three older girls trained to lead the conversation.

There's much talk in Niger of a 'demographic dividend' - the ability of a young and active workforce to catapult economies out of poverty

She's had four children, but despite all the talk of "spacing" births - leaving it longer between each child - she won't say how many more kids she wants.

"It all depends on Allah," she said. But it is a little more complicated than that.

After dodging a question asked a few different ways, the translator finally explained.

As a woman, she has no say. It depends on her husband. If her husband decides to stop having children, then she can go to the health centre and stop.

"But here it all depends on the husband. The last word is from the husband."

Smaller families

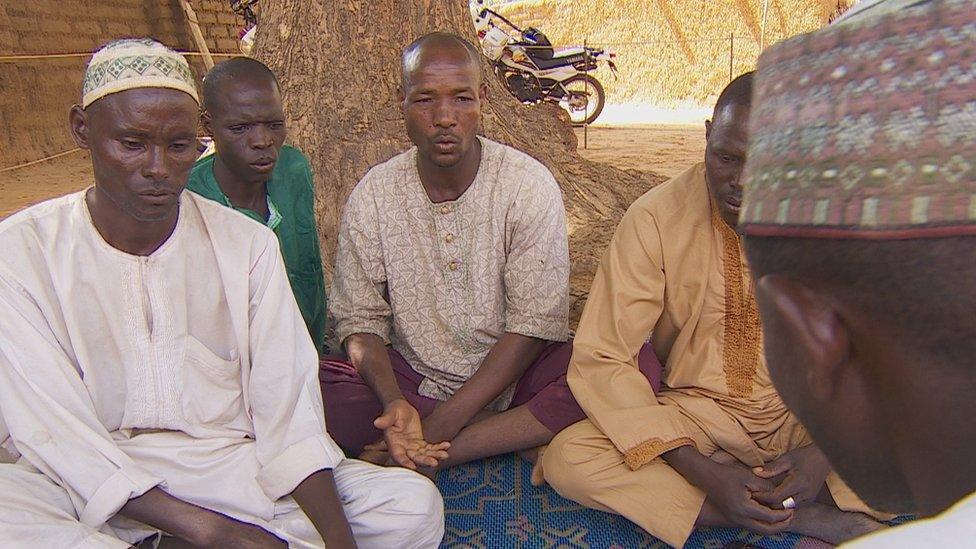

And so on the other side of town the men are sitting cross-legged under a tree and chatting about similar things - they call it husband school.

In Niger, women have an average of 7.6 children each - and in rural Zinder the rate is even higher

Even if many people are persuaded, the dramatic growth of population in Niger will take a long time to slow down

Health, education and talk of the millet harvest is interspersed with chats about breastfeeding and spacing children.

Although Musa Malamharu, 47, is leading the conversation, he has two wives and 15 children, and is expecting to have at least two or three more.

It's part of the same programme - Project Sawki they call it - and the aim is to reduce the number of women dying in childbirth and children dying before the age of five - as well as trying to encourage smaller families.

If there's more certainty in life people don't need as many children, but it's getting over the "national characteristic".

Mudaha Musa, 27, seems persuaded that five or six children - two or three more than he has at the moment - are probably sufficient.

"Truly there is a problem here with having too many children," he admitted, "but with husband school we've begun to see the benefits."

Education appears to be the key to reducing the number of babies born.

At a mobile clinic well off the main road a small open room is packed full of women and small children.

The nurses are handing out different contraceptive methods for the crowd to inspect.

Experts says chaos looms if Niger does not come to terms with its spiralling population

There are condoms, femidoms, pills, inter-uterine devices and even a discussion about birth control implants.

That's when Nana Aisha, 28, stepped up and said that's what she's agreed - despite fears about the pain and the dangers - to have a three-year implant injected in front of everybody.

"I'm just going to show to the other ladies, because there are some false rumours that it might be something that can get stuck inside of muscles," she said, and it was over in an instant.

Some of the women gathered round to prod and poke at her arm - the implant clearly visible beneath her skin.

She has three children, but will put off having any more for at least the next three years.

"My husband is an educated person. He's actually the one who's encouraging me to go to the health centre for family planning," she said.

But even if many people are persuaded, the dramatic growth of population in Niger will take a long time to slow down.

Its population of 21 million people is predicted to exceed 68 million in the next 30 years.

"Yes the culture is changing. Because it's women themselves who understand that having many children is a problem for themselves," said midwife Furera Umarou.

She believes those couples who are persuaded may have four or five children rather than eight or nine - it's a start.

There's much talk of a "demographic dividend" - the ability of a young and active workforce to catapult economies out of poverty as fertility and mortality decline, but that needs investment and jobs for them to fill.

"If we don't capture the benefits of the demographic dividend, we will be thrown into a total state of disequilibrium," said Dr Hassane Atamo, head of the government's family planning division.

"That could threaten the survival of the country and encourage different things like terrorism and immigration."

A vast pool of jobless young people could be set on the migrant trail to Europe, or into the hands of Islamist extremists like Boko Haram.

Massive population growth is everyone's problem.

- Published23 June 2017

- Published1 June 2017

- Published27 March 2017

- Published16 March 2017

- Published11 September 2015