Why don't many British tourists visit Victoria Falls?

- Published

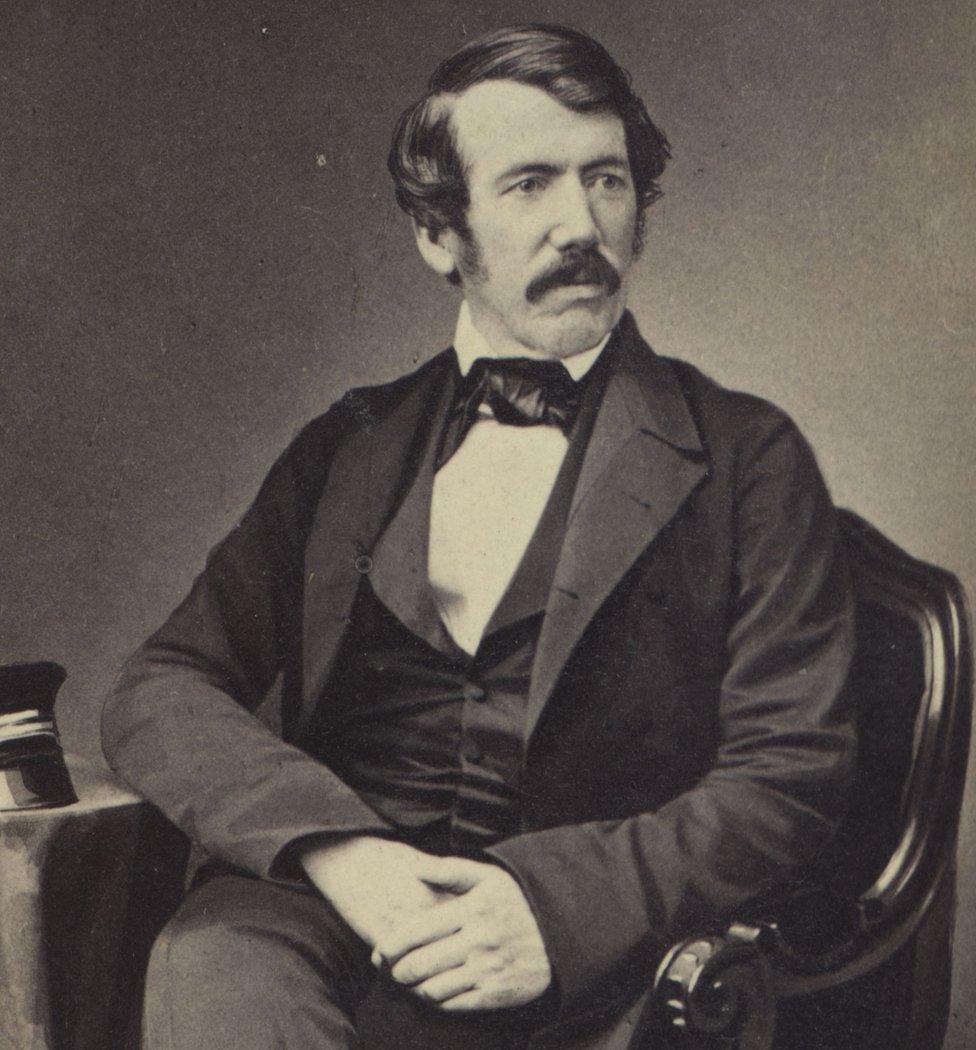

The statue of David Livingstone next to the Victoria Falls has few British visitors

In August 1934, a memorial statue to one of Britain's greatest national heroes, David Livingstone, was unveiled alongside his beloved Victoria Falls.

A thousand people attended the grand ceremony, including British government dignitaries and hundreds of Africans, some of whom had travelled for days to honour him.

Fully 60 years after the explorer's death, Livingstone's almost mythical status was undiminished.

A Christian missionary who risked his life many times to expose - and ultimately end - the evils of the East African slave trade, he introduced the world to one of its natural wonders, and was the first European person ever to walk across Africa from coast to coast, exploring and mapping the geography of the "dark continent".

David Livingstone - shown being attacked by a lion in this 1850 illustration - travelled with few servants and porters

Images of the life-sized bronze on the banks of the Zambezi were broadcast across the British Empire, countless school children thrilling to the stories of Livingstone's adventures and achievements.

Today, visitors still file past the statue on their way to experience the humbling majesty of the Zambezi as it plunges over the towering First Gorge.

But the British are notable by their absence.

Profound irony

Official figures from the Zimbabwe Tourism Ministry show that, since the turn of the millennium, the statue has rarely heard an accent from the United Kingdom, never mind voices from Livingstone's native Scotland.

In 2015, there were more Italian visitors than Britons, about twice as many Australians and French, three times as many Germans and seven times the number of Americans.

David Livingstone dreamed of turning the falls he first saw in 1855 into a major tourist attraction

The irony is profound.

It was Livingstone's dream to turn Victoria Falls into a tourist attraction, his journals imagining paddle-steamers bringing visitors from the mouth of the Zambezi to witness their splendour.

There is a similar Britain-shaped hole at the quintessentially English Victoria Falls Hotel, where the flying boat from Southampton once stopped on its way to the Cape.

The Victoria Falls Hotel dates back to 1904

Pink gins are sipped on the lawns overlooking the Darlington-built steel bridge that has spanned the Zambezi gorge since 1905.

Pictures of British kings and queens adorn the walls, alongside animal heads and zebra skins.

The current Queen stayed at the hotel in 1947.

Uncomfortable relationship

A framed photograph shows the then-Princess Elizabeth with her father, George VI, watching the mighty Zambezi tumble over the precipice, an image that inspired huge numbers of British tourists to follow the Royals to the falls.

A visit by then-Princess Elizabeth and George VI to Victoria Falls in 1947 helped boost the area's appeal

But in recent years, that flood has become a trickle.

Why?

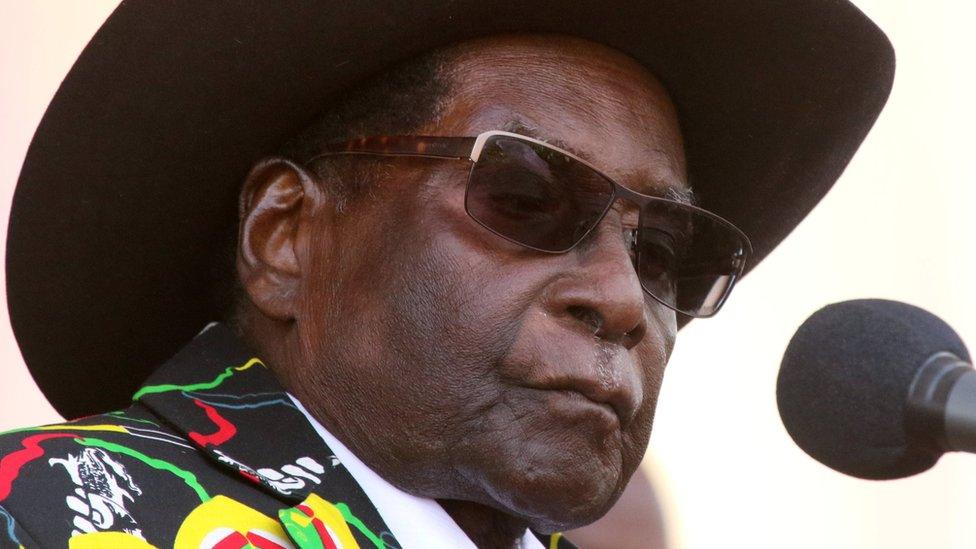

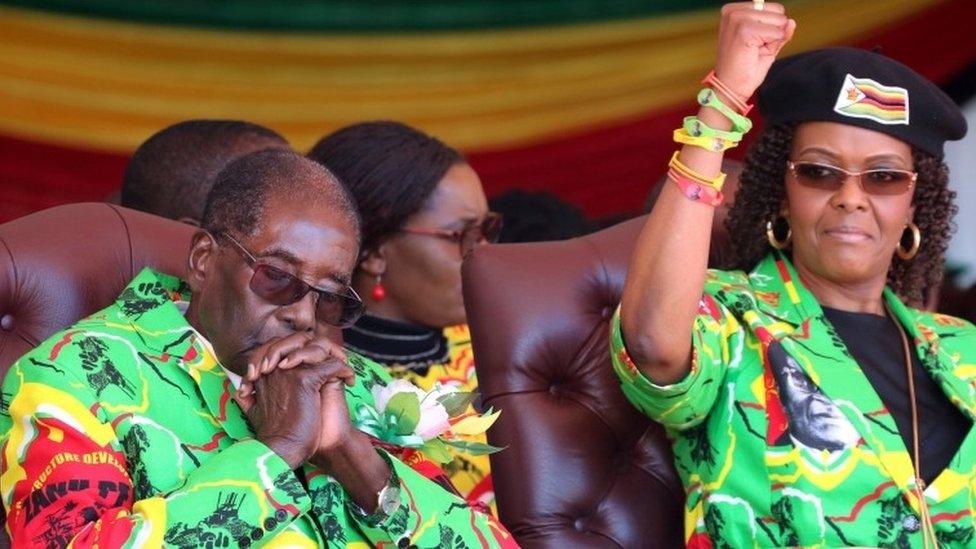

Robert Mugabe. Livingstone's statue stands on what is now Zimbabwean soil, and Britain has an uncomfortable relationship with its former colony.

Most UK tourists visit what locals call Mosi-oa-Tunya (The Smoke That Thunders) from the Zambian side, north of the river, where consciences may feel less troubled.

Limited sanctions remain in place against Zimbabwe, external, although these are mostly to do with arms dealing and individuals, including Robert and Grace Mugabe. Tourists can travel to the country.

And this corner of Zimbabwe is making a plan to woo the British back.

Victoria Falls are regularly dubbed one of the world's seven natural wonders

The border town of Victoria Falls exists only for tourism.

Emergency session

But after President Mugabe began forcibly confiscating land from white farmers in 2000, the country's status as an international pariah saw the number of foreign visitors there dwindle almost to nothing.

A decade later and facing ruin, business leaders in the town met in emergency session.

It was clear the Mugabe government was not in a position to help them.

The economy was in tatters, ravaged by hyperinflation, the national bank had to issue trillion-dollar notes.

Shops were empty and the people haunted by desperate poverty and fear.

The roads had not been maintained, anti-malaria measures had all but been abandoned, the international press painted a picture of a country where white Westerners were treated as the enemy.

What hope of attracting foreign tourists to that?

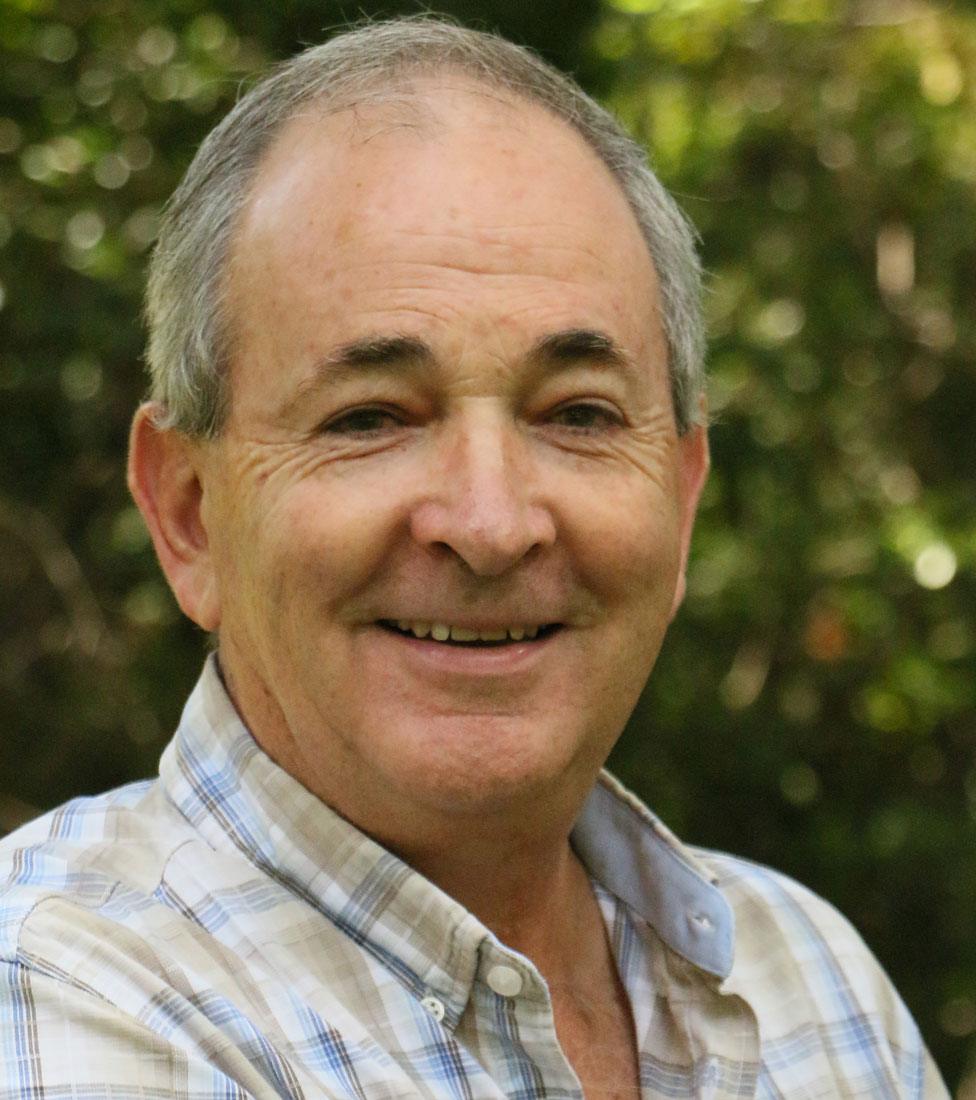

Victoria Falls hotelier Ross Kennedy galvanised fellow business owners to try to address the town's problems

"If you have a pothole outside your house, there is no point in moaning about it if no-one is going to fix it," says Ross Kennedy, the hotelier behind the crisis meeting.

"We got together and agreed there are times when it is necessary to fix the pothole yourself."

So that's what they did, both metaphorically and literally.

"The town council said it could provide the labour and the trucks. We all chipped in to buy gravel and tar. It was a real town effort - hotel operators, transport operators, activity operators all helped fix the roads," Mr Kennedy says.

Innovative solutions

It was the same strategy with the fight against malaria. The council didn't have the foreign currency to buy the necessary chemicals to spray, so local businesses funded what was required, offsetting the cost against their rates.

They also tackled the security issue. As the owner of a number of local resorts, Mr Kennedy knew his business could never thrive if guests felt unsafe.

"Myself and three other guys in Vic Falls funded around 10 or 12 people to act as tourist police," he says.

The tourist police are jointly funded by local businesses and the tourism authority

Initially sceptical, the government's tourism authority soon decided the friendly uniformed teams were a great way to reassure potential visitors.

"There are many more tourist police now," Mr Kennedy says.

"We pay half, and the tourism authority pays half.

"The local police have become more supportive, and now train the recruits in basic police work and public relations."

The latest plan is for private business to buy new software that would speed up the issuing of visas at the border, reducing the process from three minutes to 30 seconds, ending the long queues that are many tourists' dreary introduction to Zimbabwe.

As a result of these innovative joint ventures, Victoria Falls has managed to insulate itself from many of Zimbabwe's problems.

"We are in a bubble here," says Africa Albida Tourism's Michele Vickery.

"When the state could not be relied upon, the people of this community just looked out for each other. The result is that tourism is picking up again."

The Americans are coming back, both young backpackers and wealthy baby-boomers. Australians, Germans, French and Italians are beginning to arrive again too. The town is much busier. But where are the British?

"Britain is still a bit behind," Mr Kennedy says.

"I think the main reason is the colonial past. There is an element who say: 'There is no way I am spending a dollar in a country that behaves like that, where X, Y or Z is in power,' to which I say, 'I am not your moral compass.'"

Scramble for Africa

The British Embassy has been lobbied by town businesses to push for the inclusion of a paragraph in the UK's official Zimbabwe travel advice, external, saying that warnings of violence, assaults by security forces, shortages of fuel and water do not apply to Victoria Falls.

But the advice has not changed.

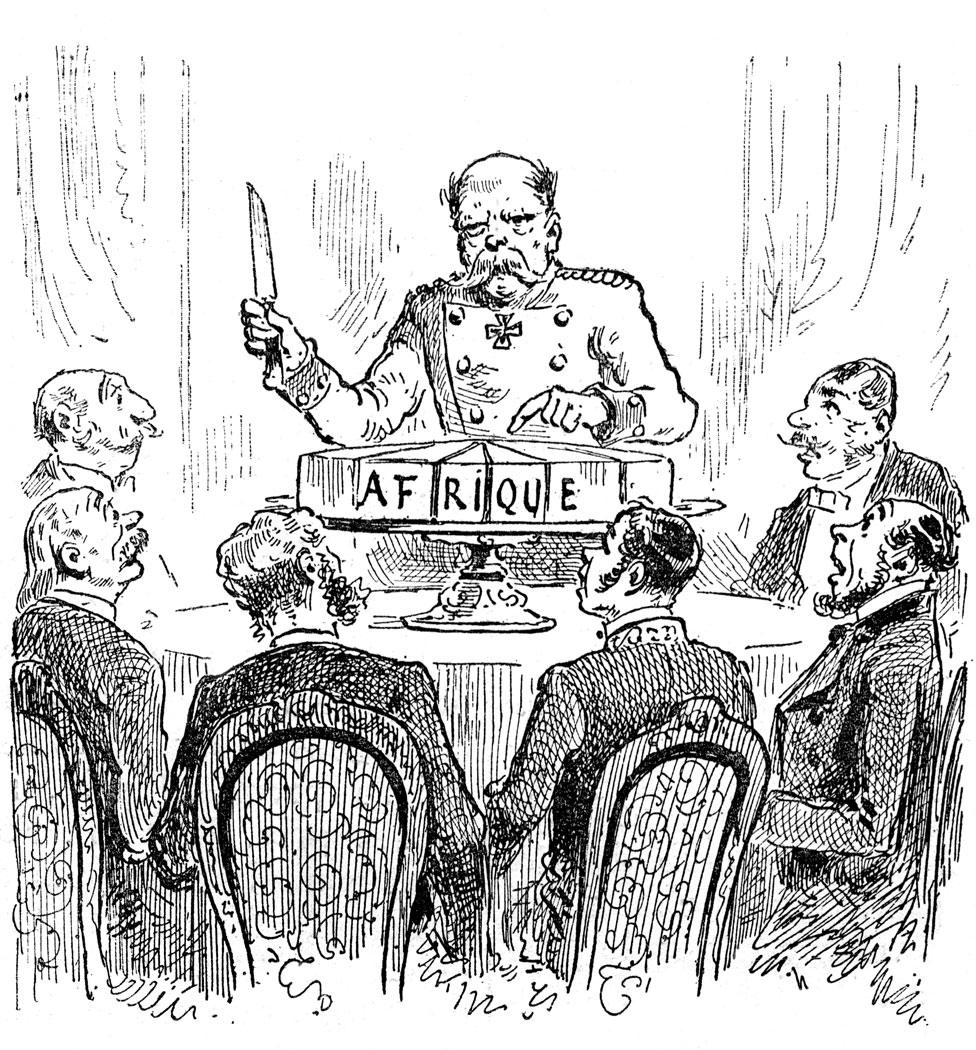

The UK's relationship with Zimbabwe was formalised following the Congress of Berlin in 1885, part of the so-called scramble for Africa.

This French cartoon from 1885 mocks German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and his fellow European leaders slicing up Africa like a cake

Western powers sat around a table carving up the continent and claiming territorial rights.

Britain walked away with the keys to exploiting the area it would later call Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

The man granted the honour of unveiling David Livingstone's statue on the banks of the Zambezi in 1934 was the explorer's nephew, Howard Moffatt.

A very different personality to his liberal and reforming uncle, Moffatt had just stepped down as prime minister of Southern Rhodesia, having pushed through the Land Apportionment Act of 1930.

Moral ambiguity

The legislation barred African landownership in the British Crown colony, outside special reserves.

The best land was allocated exclusively to white people, farms where the seeds of black grievance and bitterness were sown.

Mr Mugabe's violent seizure of white-owned property 70 years later might be seen by some as the bloody consequence of that colonial arrogance.

In unusually candid comments in 2015, President Mugabe admitted there had been flaws in Zimbabwe's controversial land reform programme

The moral ambiguity that lies behind Britain's relationship with Zimbabwe surely helps explain the persistent reluctance of many in this country to risk association with it.

Since 2015, Victoria Falls has had its own international airport with a runway capable of taking the largest passenger aircraft.

The townsfolk have pressed airlines to begin direct flights from Europe, but British carriers have so far not expressed much interest.

Political instability

UK airlines say there are commercial and logistical reasons for not flying directly to the resort at the moment.

It is easy to find reasons not to step upon the troubled lands of Zimbabwe.

At the moment, the country faces an acute cash shortage. cash machines are usually empty, and American dollars - now the legal currency - are so scarce, hawkers beg tourists for their shoes and clothes.

There are concerns that dreaded inflation is returning.

People worry about social and political instability, with elections next year and, at some point, transition to a post-Mugabe Zimbabwe.

But the fundamentals of this beautiful and enchanting country are pretty solid.

The landscape and wildlife are stunning. The climate is benign and the soil fertile. Communities have become resilient and practical.

There are a few straws in the savannah wind. Some British tour operators have recently returned to Zimbabwe, and hoteliers report UK bookings are creeping up, although there is still a long way to go.

Zimbabwe's Tourism Minister Walter Mzembi points out that visitors to Niagara Falls in North America bring in income double that of the whole of Zimbabwe's economy.

"They are spending $30bn [£23bn] whilst Victoria Falls, a natural wonder of a higher magnitude, receives just $1bn," he told the Zimbabwe parliament.

Victoria Falls can shield itself from some of Zimbabwe's contemporary woes.

But the grim countenance of Livingstone's statue, staring resolutely at the great falls, reminds us of the struggle to navigate a path through the thorny undergrowth of African history.

- Published30 August 2023

- Published24 August 2017

- Published9 August 2017

- Published27 July 2017

- Published24 July 2017

- Published13 July 2017