Can Nigeria and Cameroon learn any lessons from Catalonia?

- Published

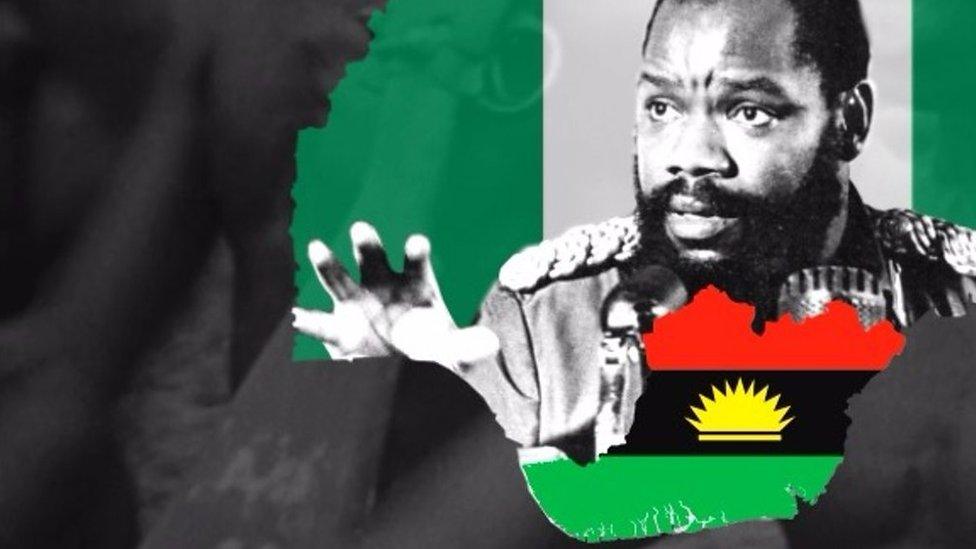

Some ethnic Igbos feel Nigeria's central government does not represent their interests

The crisis in Spain's Catalonia region is being closely watched in Nigeria and Cameroon, where secessionist movements have been stepping up campaigns for independence, as BBC Pidgin editor Adejuwon Soyinka reports.

Many Nigerians and Cameroonians were looking to Spain, hoping it would find a peaceful solution to demands for independence in the Catalan region.

But this changed when violence broke out over the independence referendum held in Catalonia on 1 October in defiance of the Spanish central government and courts.

"What both the campaigners for Biafran and Catalan secession have in common is the heavy-handedness (and empty-headedness) of their federal governments," wrote political commentator Onyedimmakachukwu Obiukwu, external.

He hails from the Igbo ethnic group which is at the centre of the campaign to create the breakaway state of Biafra in south-eastern Nigeria.

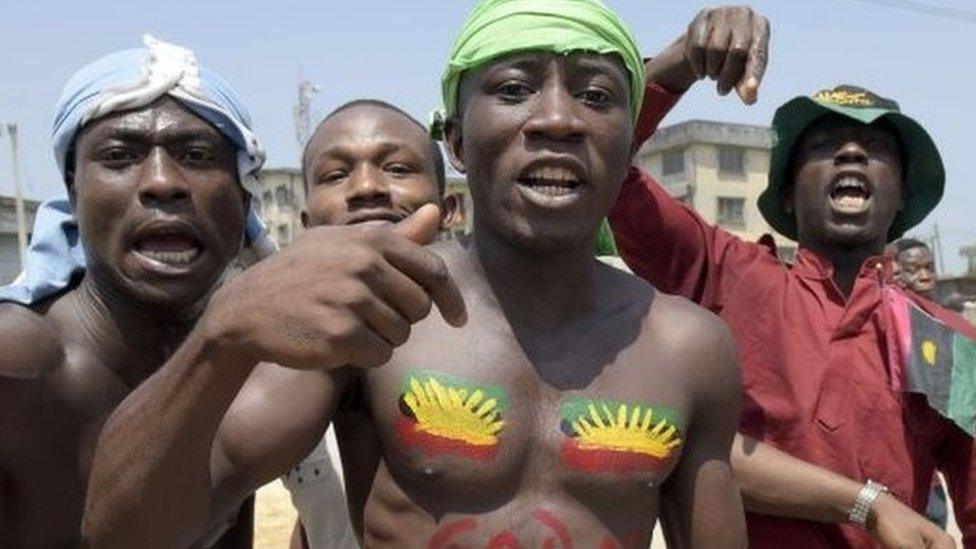

Just as Spanish police have been accused of using excessive force against Catalans who took part in the disputed vote, Nigeria's military has been accused by the Indigenous People of Biafra (Ipob) movement of "invading" the south-east, killing innocent people and raiding the homes of its leader, Nnamdi Kanu, and his father, Eze Israel Kanu.

Biafran War veterans remember the conflict 50 years on

The raids were condemned as "primitive and cowardly" by another secessionist movement, the Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra.

The military has repeatedly defended what it calls Operation Python Dance II - the heavy deployment of troops to the south-east to quell pro-independence protests.

It says it seized weapons during the raid on the home of Mr Kanu senior.

Neighbouring Cameroon has also been hit by calls for independence - this time for the two English-speaking regions in the majority French-speaking country.

Anglophones have been protesting for months, saying they faced marginalisation.

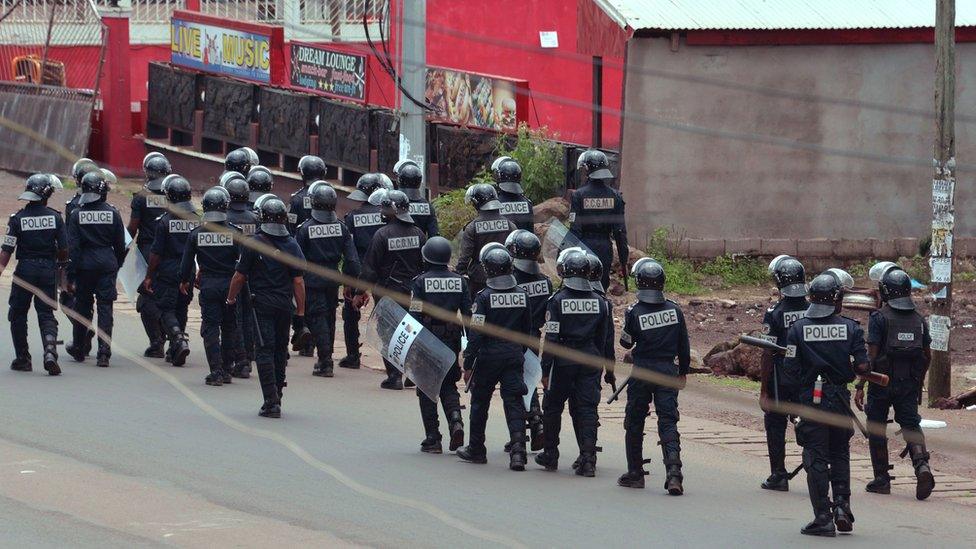

On 1 October, security forces shot dead 17 protesters during clashes in the region, according to Amnesty International.

The authorities even went as far as imposing an internet blackout in the North-West and South-West provinces, which are the two majority English-speaking areas.

Banned as terrorist group

Prior to the independence vote in Catalonia on 1 October, advocates of self-determination in Cameroon and Nigeria had looked up to Spain as a model for what they described as a rancour-free "divorce".

They were quick to point out that Catalans were after the same thing and the Spanish government had shown restraint in its approach.

This changed to some extent when national police were sent in to disrupt the unofficial independence referendum the regional Catalan government had organised.

However, it is still free to argue its cause.

In Nigeria, the military viewed Ipob as a terrorist group and the authorities got it proscribed as such.

Under new laws it is now an offence bordering on terrorism to be a member of Ipob, or be found with posters, flyers or even clothing with Ipob's logo or inscription anywhere in Nigeria.

Biafra in brief:

Ipob claims these existing states would make up an independent Biafra

First republic of Biafra was declared by Nigerian military officer Odumegwu-Ojukwu in 1967

He led his mainly ethnic Igbo forces into a deadly three-year civil war that ended in 1970

More than one million people lost their lives, mostly because of hunger

Decades after Biafra uprising was quelled by the military, secessionist groups have attracted renewed support

They feel Nigeria's central government is not investing in the region

But the government says their complaints are not particular to the south-east

The Biafran war explained

The whereabouts of its leader Nnamdi Kanu is now a subject of controversy - his supporters say the army has detained him but the military authorities have denied this.

Several regional observers, like John Nwodo, head of Ohaneze Ndigbo, a socio-cultural group in south-east Nigeria, have criticised the authorities' strategy saying it was alienating and "wrong headed."

He argues that such heavy-handed actions are likely to radicalise the community and give rise to militant groups in the shape of Boko Haram, which continues to wreak havoc in northern Nigeria.

But Information Minister Lai Mohammed counters this argument saying that the government's operation is based on those exact fears:

"We didn't want to have another Boko Haram on our hands," he told BBC Pidgin.

Peaceful protests

One major difference is that Catalan separatists have been elected to run a regional government.

Nigeria has a federal system, designed to ward off demands for independence, but secessionists have not been elected to any of the five Igbo-majority states - whether because of a lack of public support or heavy-handed action by the authorities is a matter of debate.

And with Ipob banned, the group is obviously unable to contest elections.

Both pro- and anti-Catalan independence protests have been held in Spain without major clashes with security forces.

However, in Cameroon and Nigeria, any public protest is immediately quashed, leading to arrests and, in some cases, deaths.

Anti-riot police patrol the streets in the Buea in the Anglophone region

Another area of difference is the level of media coverage the separatist movements are getting.

The merits of a proposed Catalan state and the challenges it would face have been part of mainstream debate in Spain.

This is in start contrast to Nigeria and Cameroon where the activities of the secessionist groups have been criminalised and mostly muted from local media coverage.

Better a secessionist in Cameroon than Nigeria?

While Nigerian authorities appear averse to the idea of negotiations with advocates of secession movements, Paul Biya, Cameroon's president of 35 years and counting, has called for dialogue.

While condemning the violence in the protests, Mr Biya said: "It is not forbidden to voice any concerns in the republic. However, nothing great can be achieved by using verbal excesses, street violence, and defying authority."

Does this make Cameroon authorities different?

Not according to Wilfred Tassang, Vice Chairman of the Southern Cameroons' Ambazonian Governing Council, which has been banned by the authorities.

He says such a statement from Mr Biya is just a façade to cover what he described as the government's atrocities against people from the Anglophone region.

There are fears that if the situation in these countries is not handled carefully, a full-scale armed conflict may be inevitable.

And this appears to be the worry of Nigeria's President Muhammadu Buhari.

"As a young army officer, I took part from the beginning to the end in our tragic civil war costing about two million lives, resulting in fearful destruction and untold suffering," he said during his independence day speech on 1 October.

"Those who are agitating for a re-run were not born by 1967 and have no idea of the horrendous consequences of the civil conflict which we went through… Those who were there should tell those who were not there, the consequences of such folly," the president warned Nigerians.

- Published6 July 2017

- Published5 July 2017