International Criminal Court probes Burundi 'crimes against humanity'

- Published

The decision was made on October the 25th - two days before Burundi's official withdrawal from the ICC

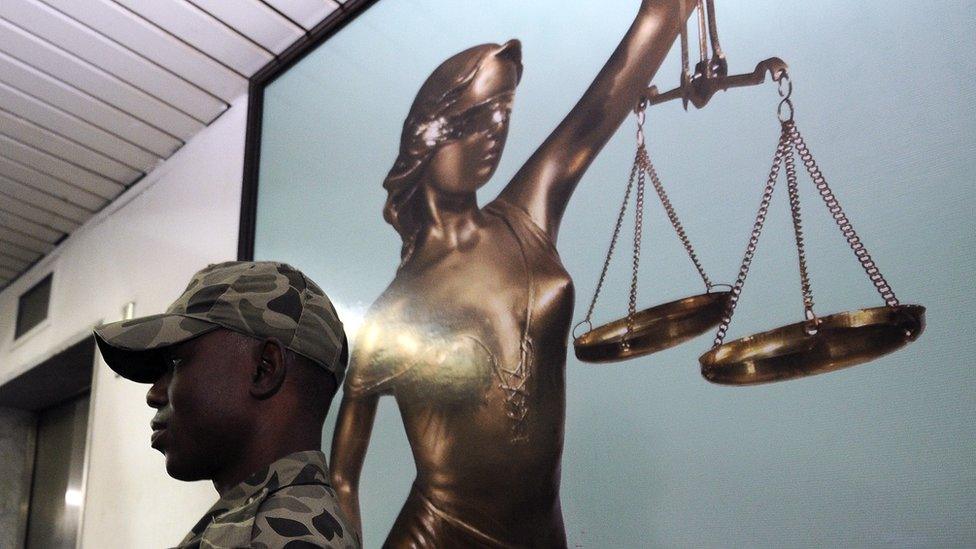

The International Criminal Court (ICC) has authorised prosecutors to open a full investigation into alleged crimes against humanity in Burundi.

The announcement comes just weeks after the country became the first member to withdraw from the international court.

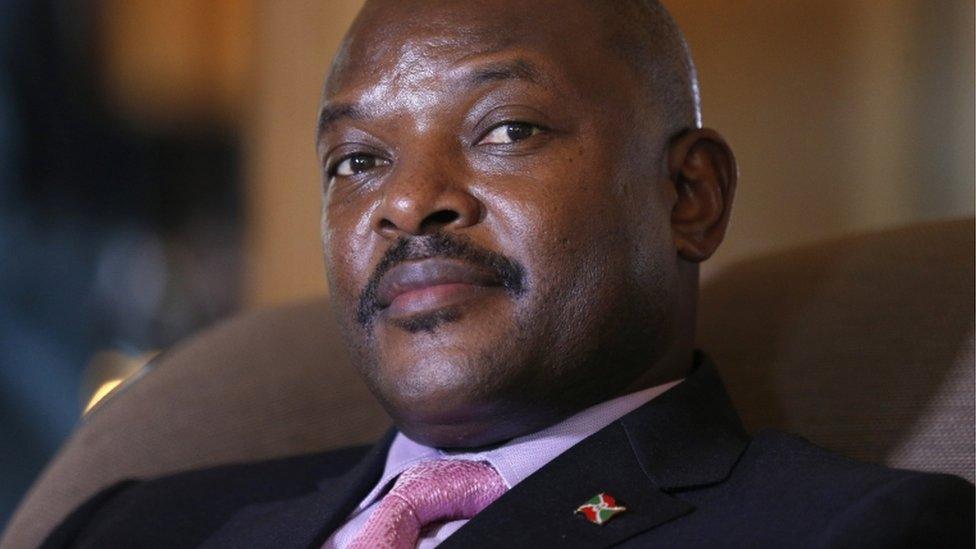

Unrest broke out in Burundi in 2015 after President Pierre Nkurunziza decided to run for office a third time.

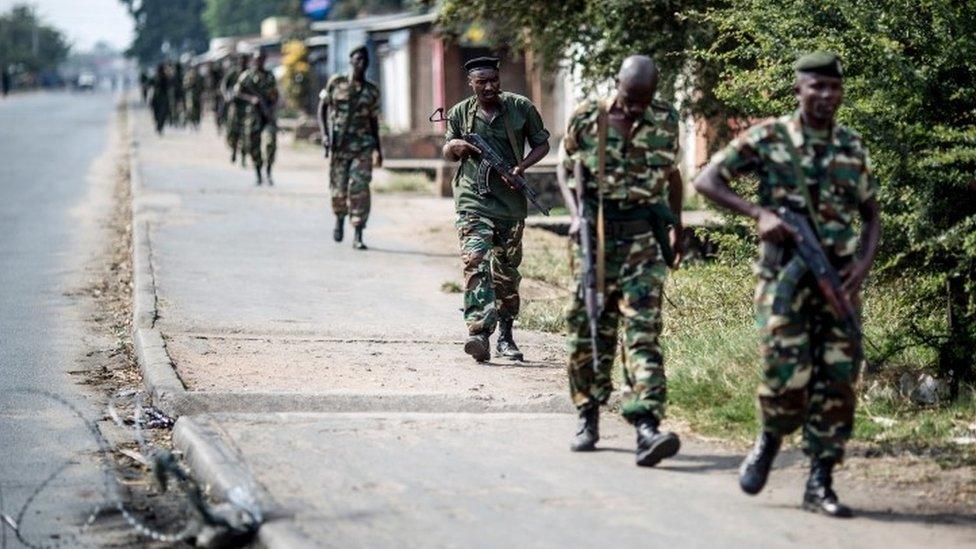

Rights groups say hundreds of people were killed. UN investigators say there is evidence of crimes against humanity.

They issued a report in September detailing killings, torture and rape, which they say have been committed largely by government forces - but also by opposition groups.

The UN report urged the ICC, based The Hague, to launch an inquiry.

In 2015 security forces launched a crackdown after major protests against President Nkurunziza's decision to stand for re-election. Groups disagreed over whether the candidacy was constitutional.

The ICC statement said hundreds of people had disappeared in the country, external, and thousands had been illegally detained and tortured.

As many as 400,000 people may have been displaced in the violence, it said.

President Nkurunziza has been in power since 2005 and survived an attempted coup in 2015

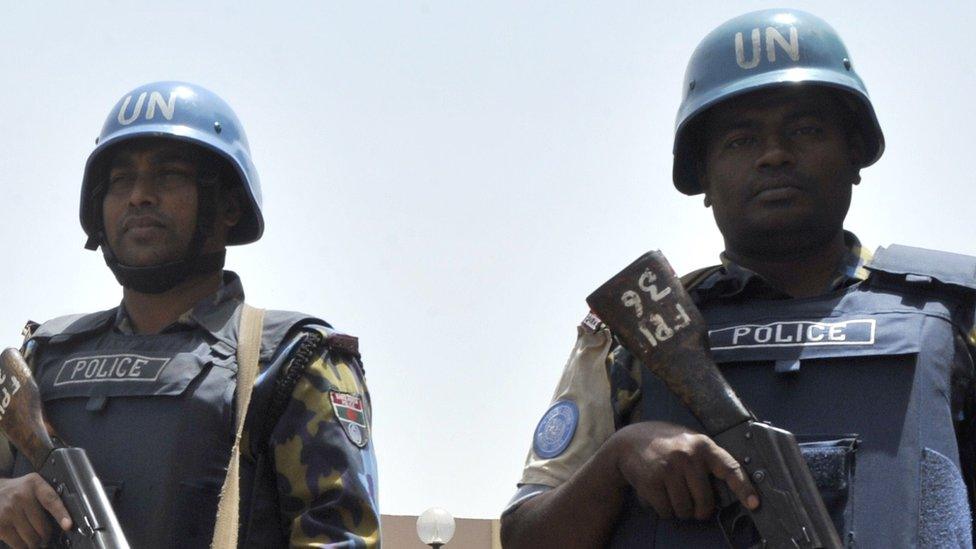

Burundi withdrew from the ICC on 27 October after accusing the court of deliberately targeting Africans for prosecution. The African Union called for a mass withdrawal of member states in February over the issue.

The decision to approve the investigation was made two days before Burundi's withdrawal but only made public on Thursday to protect witnesses, the ICC said.

But the case of Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir, one of the ICC's "most wanted", has highlighted the difficulty of getting a non-member to co-operate in surrendering suspects.

Responding to news of the ICC case, a senior Burundian presidential spokesperson accused the court of "outrageous lies to implement Westerners' hidden agenda to destabilize Africa".

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The country's justice minister, Laurentine Kanyana, called the court's decision a "fraud".

She said her government had no intention of co-operating with the investigation.

The ICC and global justice:

Based on the Rome Statute adopted in 1998, the court came into force in 2002.

It was ratified by 123 countries, and Burundi is the only one to have withdrawn. Now there are 122 - including 34 African nations

The United States is a notable absent member of the court

The court aims to prosecute and bring to justice those responsible for the worst crimes - genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes

But only Africans have been prosecuted so far, fuelling criticism

- Published4 September 2017

- Published3 August 2016

- Published7 November 2015

- Published22 December 2015

- Published8 March 2017