Zimbabwe latest: What we know so far

- Published

The army is upset about recent purges in the ruling party

The military in Zimbabwe has taken control of the country, putting veteran President Robert Mugabe under house arrest and announcing it was targeting "criminals" around him.

It has denied it is staging a coup, while Mr Mugabe, 93, has been pictured smiling beside army chiefs and left the house for a scheduled appearance on Friday.

However on Sunday, Mr Mugabe was removed as the leader of Zimbabwe's ruling Zanu-PF party and ex-vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa, who had been fired by Mr Mugabe two weeks before, was appointed in his place.

Military officials had feared Mr Mugabe was planning to install his wife, Grace, as his successor.

So what does this mean for Mr Mugabe and the country he has led since independence in 1980? Here is what we know.

Do you have a question about the situation in Zimbabwe? haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external

What has happened?

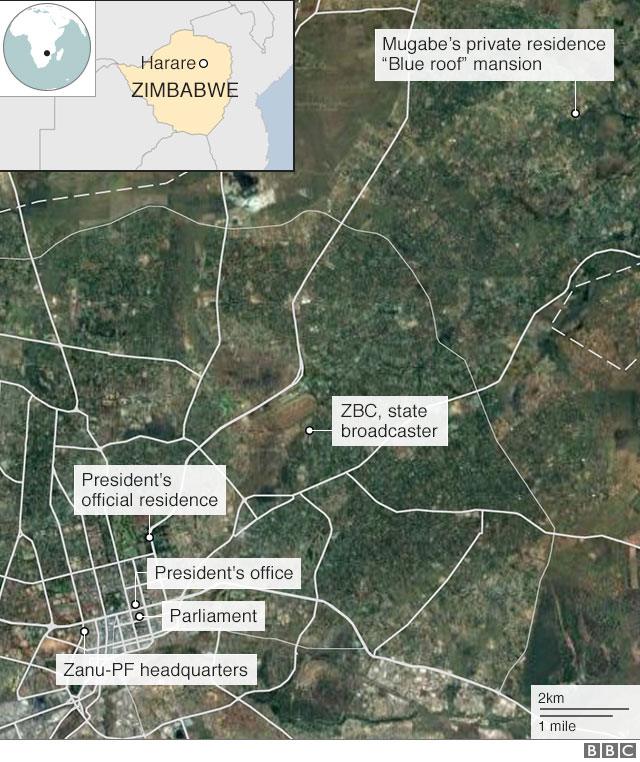

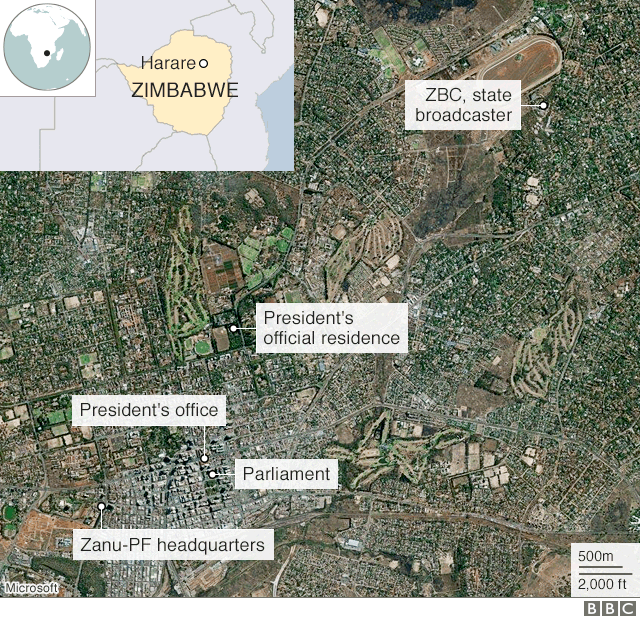

Military vehicles were spotted on roads leading to Harare on Tuesday, sparking rumours that something was afoot.

Later, soldiers seized the headquarters of Zimbabwe's national broadcaster ZBC and explosions and gunfire were heard.

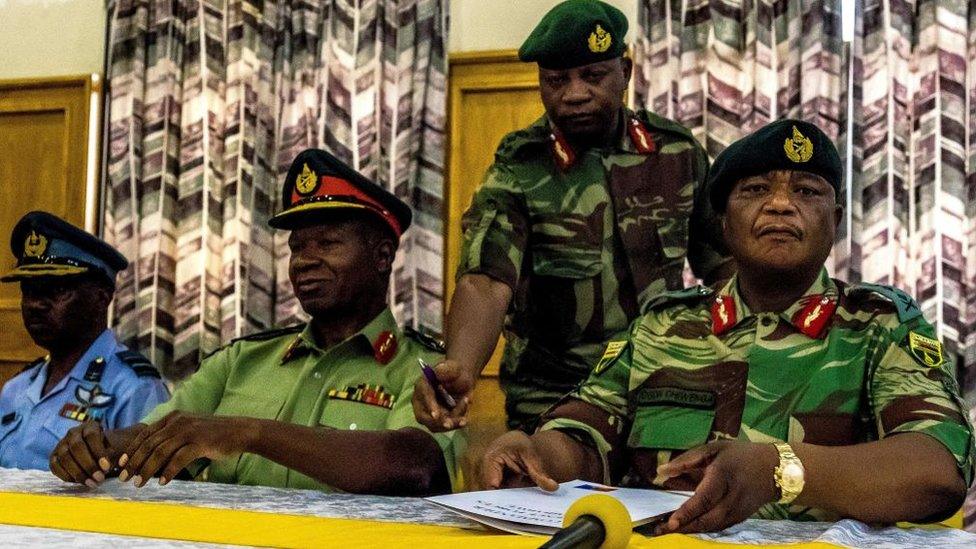

Maj-Gen Sibusiso Moyo then read out a statement on national television, assuring the nation that President Mugabe and his family were safe.

Maj Gen Sibusiso Moyo read out a statement on national TV early on Wednesday

The military was only targeting what he called "criminals" around the president, he said, denying that there had been a coup.

"As soon as we have accomplished our mission we expect that the situation will return to normalcy," he added.

President Mugabe was being held at his home and was "fine", according to a statement by South Africa's President Jacob Zuma, who spoke to him on Wednesday.

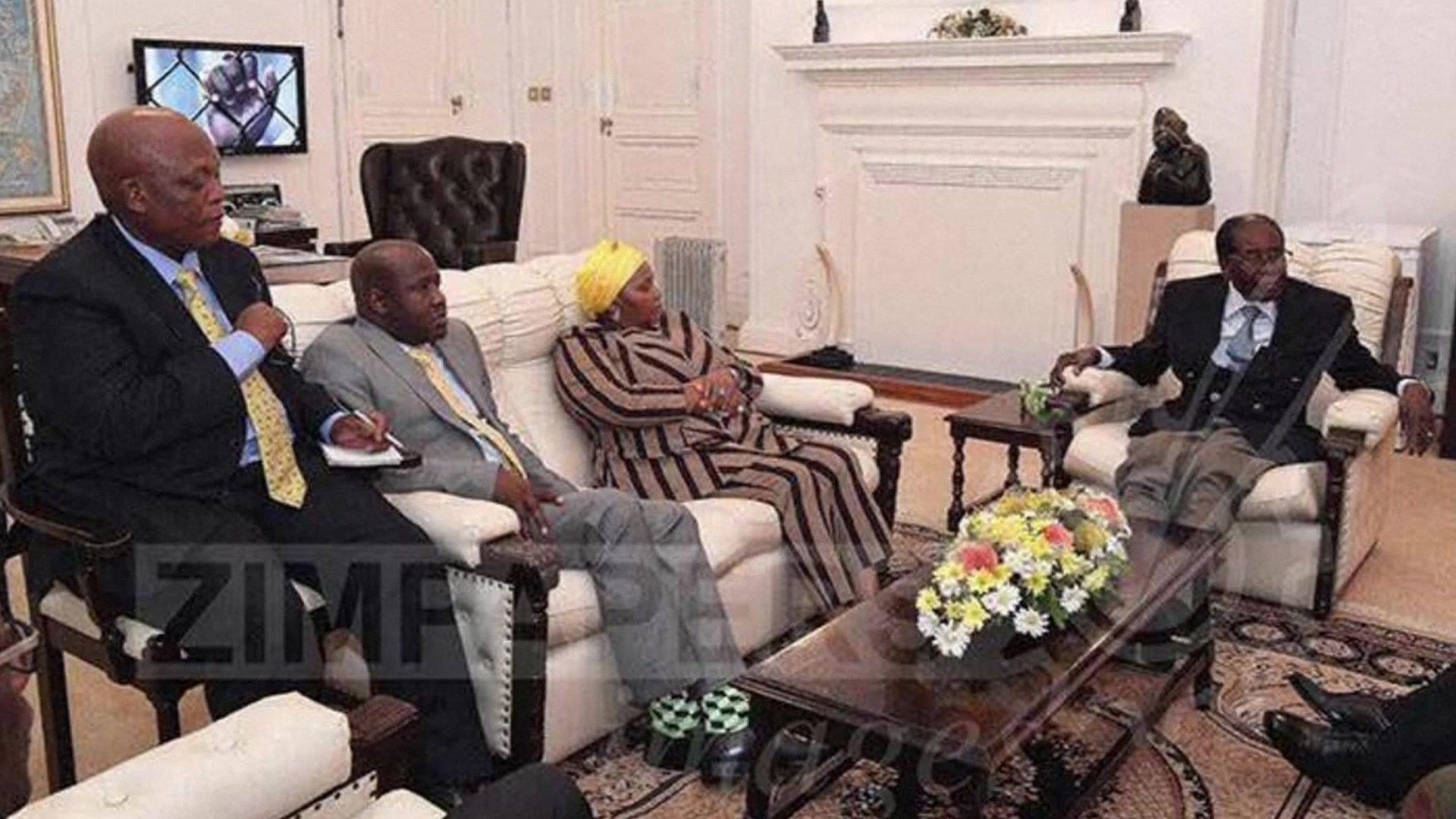

On Thursday, he was pictured taking part in talks with Gen Constantino Chiwenga and South African government ministers at State House.

The South African envoy has been trying to help the two sides reach a deal on Mr Mugabe's future, but sources suggest he may be resisting pressure to resign.

On Friday, the president gave out degrees at a university of which he is chancellor, thereby meeting a prior commitment.

The military said on Friday that they had detained some "criminals", but they did not give names.

On Saturday, tens of thousands of Zimbabweans took to the streets of Harare to urge Mr Mugabe to go. It was led by veterans of the country's war of independence, who last year turned against him.

"There's no going back about Mugabe," said veterans leader Christopher Mutsvangwa. "He must leave."

On Sunday, Zanu-PF sacked Mr Mugabe as its leader.

Meanwhile main opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, who has been receiving cancer treatment in South Africa, returned to Zimbabwe amid suggestions that his Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) could form part of a possible transitional government.

And what hasn't happened?

There has not been any official government response to events.

Nor have we heard directly from President Mugabe or his wife Grace which, according to analysts, suggests they have lost control.

When Mr Mugabe spoke at the university on Friday, he did not make any political comment.

And there are no reports of any members of the security forces who remain loyal to Mr Mugabe intervening to defend him.

What has upset those behind this action?

This is all about the leadership succession, as Mr Mugabe's powers finally falter.

The people who fought in the 1970s guerrilla war against white minority rule still dominate Zimbabwe's government, and especially its security forces, and they are worried about losing that power, and the wealth it generates.

Last week, the army chief Gen Chiwenga warned the military could intervene to halt purges of the governing Zanu-PF that were "clearly targeting members of the party with a liberation background".

Who is Grace Mugabe?

This was obviously a reference to the sacking last week of Mr Mnangagwa, Mr Mugabe's once loyal deputy and a former defence minister, spy chief and veteran of the war of independence.

Mrs Mugabe's supporters are known as "Generation 40" or "G40" - a name which signals a changing of the guard in Zimbabwe, at least partially, 37 years after independence.

So this military action is the old guard reasserting its authority.

Mr Mugabe was the political leader of the guerrilla war so the army has always professed loyalty to him, until he explicitly came out in favour of his wife taking over from him.

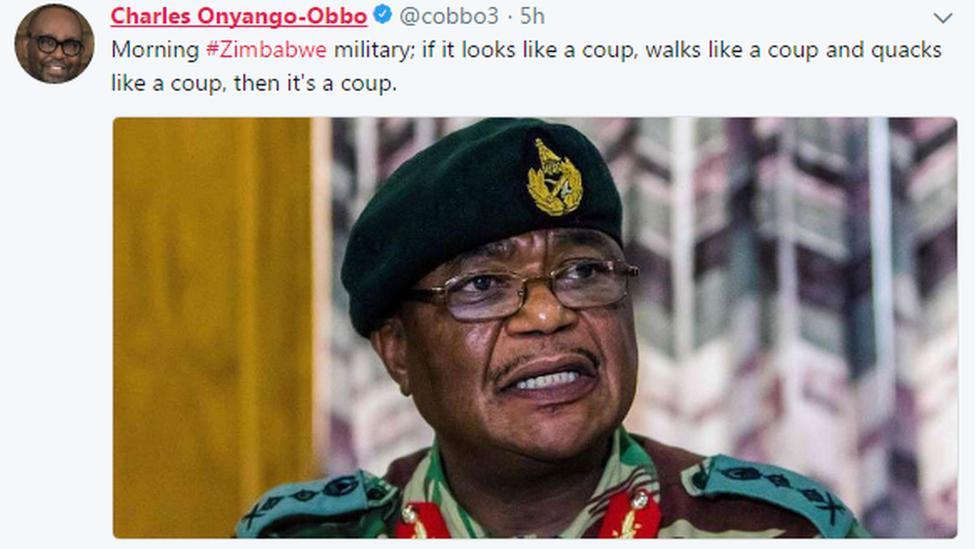

Is this a coup?

Most observers think so. The army's denial it was carrying out a coup has been mocked on social media.

The BBC's southern Africa correspondent Andrew Harding called the move an "extraordinary gamble".

He sees it as an internal power struggle within Zanu-PF "and whoever emerges victorious can expect a newly purged party to fall obediently into line".

He says it is important to remember that Mr Mugabe is not being challenged by Western governments, or by Zimbabwe's political opposition, or by a mass uprising against economic hardship.

What is the mood in the country?

There appears to have been no dramatic effect on normal life. People say shops have opened as normal.

The military thanked the public "for remaining patient and peaceful as they carry out the operation".

Some Zimbabweans told the BBC that they welcomed the news, with one man expressing his thanks to the army for "taking out the tyrant".

Zimbabweans react to the news that troops had taken control

One resident of Harare though told the Press Association: "I don't think I see how anything could possibly be different. If we wanted to see any change we would have to assassinate about 5,000 people all feeding from the same trough."

Reaction outside Zimbabwe

The head of the key regional bloc the African Union, Guinea's president Alpha Conde, said that the crisis "seems like coup".

He said the AU demanded that "constitutional order be restored immediately".

In his statement, South Africa's President Zuma said that he was sending a delegation to Zimbabwe to meet President Mugabe and the Zimbabwean Defence Force.

Nigeria's President Muhammadu Buhari has urged "respect for the constitution", and said every attempt should be made to save the country from "political instability".

The leaders of Botswana and the Ivory Coast called on Mr Mugabe to leave his post, both focusing on his age and the amount of time he had been president.

US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson called for a "quick return to civilian rule" and the UK - Zimbabwe's former colonial ruler - said it hoped elections scheduled for 2018 would take place as planned.

- Published16 November 2017

- Published15 November 2017

- Published21 November 2017

- Published6 November 2017

- Published30 August 2023