Mugabe and me: A personal history of growing up in Zimbabwe

- Published

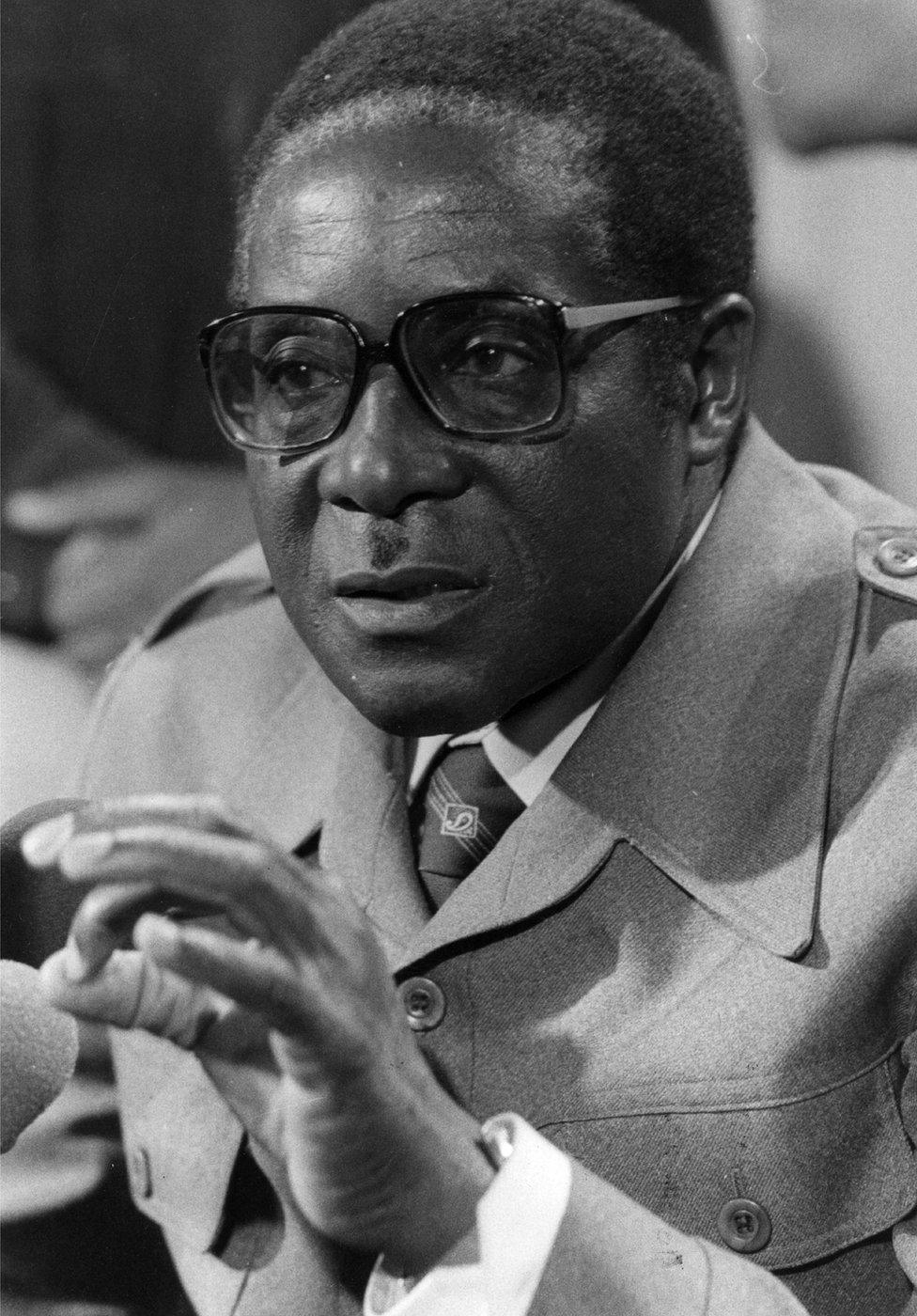

Robert Mugabe is seen as the father of the nation - Zimbabweans aged 37 or younger have known no other leader

As Zimbabweans usher in a new era, author Petina Gappah considers the long shadow ex-president Robert Mugabe has cast over her life.

Through the crackling static of the transmission came frenetic drumbeats. Then an announcer's voice, speaking emphatically, with dramatic pauses before every word. "This Is The Voice Of Zimbabwe." Then the song that all the township children came to know so well, the closest we would get to war:

"Kune nzira dzamasoja dzekuzvibatanadzo. Tererai mitemo yose nenzira dzakanaka."

I remember vividly the last two years of Rhodesia's war. As children repeating that song in the school playground, we did not know that it was an adaptation of Mao Zedong's Three Rules of Discipline and Eight Points for Attention.

"Be honest in buying and selling, return everything you borrow, pay compensation for everything you damage, do not hit or swear at others, do not damage crops, do not harass women and do not mistreat prisoners."

These principles, translated into the Shona language and set in song, were the code of conduct for the struggle for independent rule in Rhodesia.

'His voice was rich and beautiful'

I was eight when the war ended. It was far from our family in the township of Glen Norah in Salisbury, but the war came to us every night as my father Tererayi Mureri fiddled with our radio receiver to catch the shortwave transmission from Radio Mozambique.

I was with my mother Simbiso when the news reached us that guerrilla leader Josiah Tongogara had died. Her grieving shock was so penetrating that in my confusion, I thought we had lost a relative.

'At school the independence war was cast as a heroic struggle'

It was through this transmission that Robert Mugabe came into my life, and entered my imagination as the embodiment of the struggle.

His voice was rich and beautiful. I would later come to understand that what made his voice so unusual was that it was essentially manufactured, carrying almost no trace of his education or ethnic background.

I did not understand everything he said, but I remember that he called us always the people, not of Rhodesia, but Zimbabwe. This reminder, that this was a battle for a new country, and a new way to be in the world, was emphasised by the words that concluded each broadcast, "People of Zimbabwe, Victory Is Certain."

Hero worship

Victory finally came after a ceasefire that ended the war and negotiations in London to chart the path for the new country.

After the elections in March 1980, I sat with my parents and younger siblings as Mugabe addressed us again, this time on television as prime minister of our new country.

Mugabe: From war hero to resignation

There was that voice again, but with an image to go with it, not of a fearsome gorilla, which is how I heard the word guerrilla, but of a man in large glasses who wore a safari suit like my father's.

I found him reassuringly normal. Surely, he said, this is the time to beat our swords into ploughshares. We should become Zimbabweans with a single loyalty, to our nation, and to a common interest.

That year, we moved house. In my simplified understanding of the world then, I thought it was purely thanks to Mugabe that my parents were able to buy a new house in a former whites-only suburb that had a library with more books than I could have dreamt of. In my mind, I associated Mugabe with these riches.

I learned more about Mugabe the guerrilla in history lessons at secondary school.

"Seeing him on television for the first time I noticed he wore a safari suit like my father's"

Our O-Level class of 1988 was the first to study under the new curriculum. So we learned that the history of all society is the history of class struggle. The independence war was re-cast as a heroic, historically inevitable struggle between the black socialist majority and white minority capitalism.

I pored over the black and white pictures of Mugabe and other independence leaders. I fell in love with African history.

By the time I went to the University of Zimbabwe to study law, I was a budding Marxist-Leninist. My feelings for Mugabe were approaching hero worship.

Then came a shift.

Political awakening

In my first year, I attended the ceremony for that year's graduating class with a friend, Chris Giwa who was head of the student council.

As we walked to the university's Great Hall, another student, Eric Mvududu, approached President Mugabe with a petition. Mugabe's security men stopped him and roughed him up, tearing his shirt and bruising him. Mugabe walked on.

In the Great Hall, he tapped the heads of students as they knelt before him. Then came Arthur Mutambara, the leader of the previous year's council, who had led demonstrations against government corruption. As he approached the president, a great cheer went up. Mugabe rose from his seat and pumped Mutambara's hand. The Great Hall roared.

Afterwards, in Chris's room in New Hall, I sat with Mutambara (who years later became an opposition politician), the now recovered Mvududu and other friends and listened to them talk. It was the start of my political awakening.

By the end of the academic year, I had studied constitutional law, and learned, through case law on illegal detentions, that all the time I had been gulping down books as a child in the library, a state of emergency had been in place in Matabeleland, and that region had been the theatre of mass killings by the army's Fifth Brigade.

The army was accused of atrocities in Matabeleland

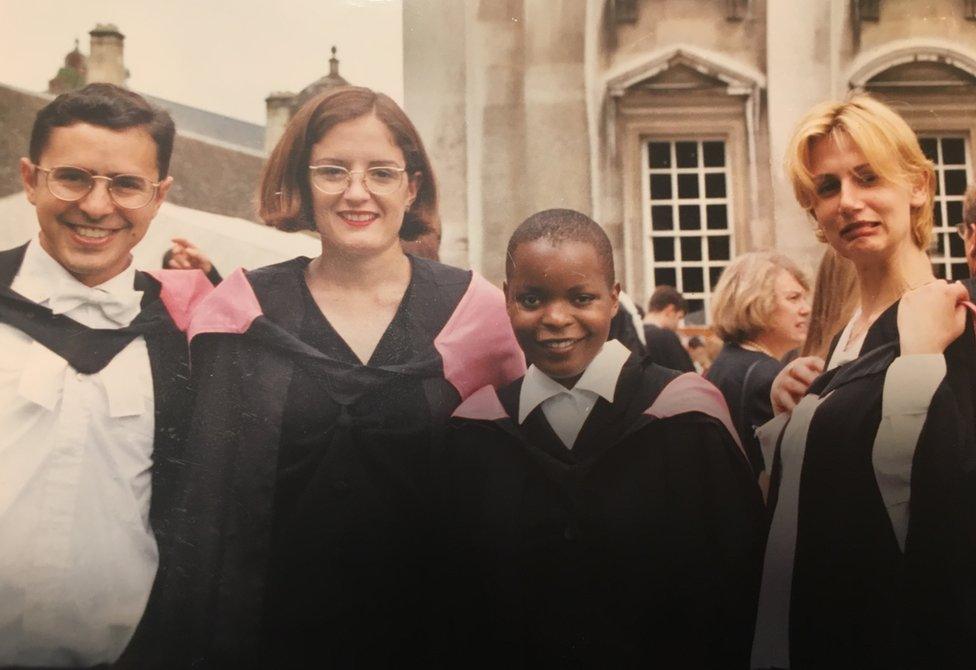

By the time I came face to face with Mugabe at my own graduation four years later, I was no longer a believer.

Gone was the hero worship, but still left was deep and conflicted respect. As the Dean read out my achievements and I knelt before him to be capped, I looked into the face of my president. In that voice, the voice I had first heard in our township house when Zimbabwe was just a dream, Mugabe said to me, "Congratulations, well done."

After her studies in Zimbabwe the author (second from right) went on to postgraduate study in Britain at the University of Cambridge

The last 17 years saw me count myself among his opponents as he waged another war, this time against the country he had promised.

We could not count all the bodies after that terrible war of liberation, but those that we could, we gave funeral rites and buried in places of honour. But how do you count the bodies of those who died in the war Mugabe waged against his own people?

Dark shadow

People like Mrs Nleya, a teacher I loved, who was trained in England and returned to Zimbabwe at the promise of independence, but died when the one oncologist in her city closed his practice, and moved to Botswana.

Or the many who died of conditions easily cured but for the shortage of drugs.

Or the border jumpers, almost all of whom were born after 1980, the Born Frees who drowned in the Limpopo on their way to South Africa, and hope.

The companies small and large, built up over years of hard work that collapsed under the weight of inflation. The livelihoods flushed away, the lost opportunities, the cheated dreams.

Zimbabwe's economy collapsed under Mr Mugabe

Was it all so that one man could rule until his death, so that he could, as opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai said so poignantly, destroy not only what he had inherited, but also what he had built himself?

Thirty-seven years after he promised that we would all build a Great Zimbabwe - but did everything he could to destroy it - Mugabe has left the stage.

No single person has influenced the direction of my life as much as he has.

To his government, I owe an education equal to that of anyone I have met, from anywhere in the world.

Both as a writer and critic, and as a lawyer, my work has been an attempt to shine some light in the dark shadow that he cast over my country.

And while I will always honour his place in history, there is not much I would not have given to be able to say back to him his only words to me, "Congratulations, well done," but this time, about his own legacy.

- Published21 November 2017

- Published3 August 2018

- Published30 August 2023