South Africa's ANC leadership battle: Top candidates

- Published

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma (c) and Cyril Ramaphosa (r) are the top candidates in the race to take over from Jacob Zuma (l)

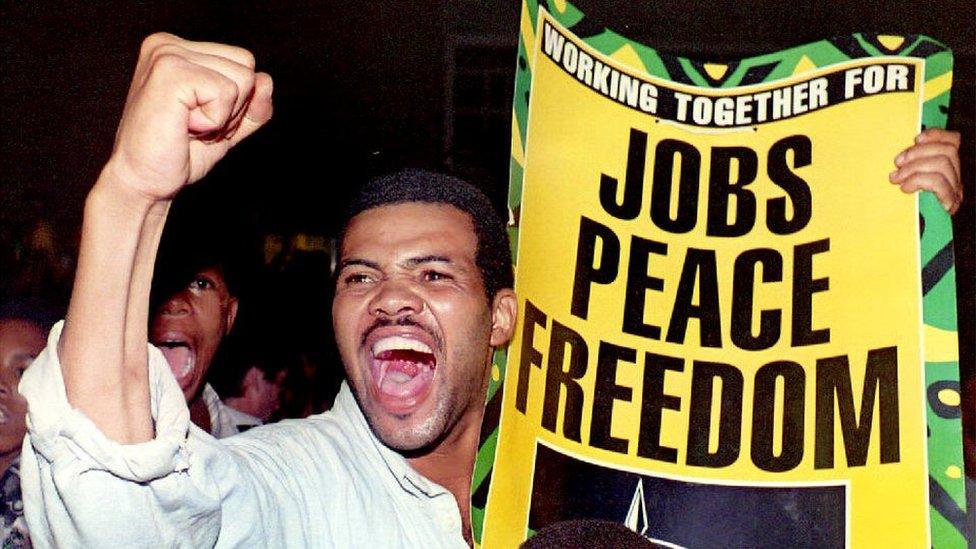

South Africa's governing African National Congress (ANC) is set to elect a new leader at a conference starting on Saturday following a fierce contest between seven candidates.

The scandal-hit President Jacob Zuma will step down as party leader, opening the way for his successor to spearhead the ANC's campaign for the 2019 general election.

The ANC has governed South Africa since the first democratic election more than 20 years ago, so there is a strong chance that whoever the party picks as its leader will also succeed Mr Zuma as president when his two terms end in 2019.

But under Mr Zuma the ANC has become wracked by infighting and allegations of corruption, raising, for the first time, the possibility that it could lose its majority.

So the incoming ANC leader will be expected to knock the party into shape, and regain the trust of voters.

While there are seven candidates, only two, Cyril Ramaphosa and Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, have a realistic chance of winning.

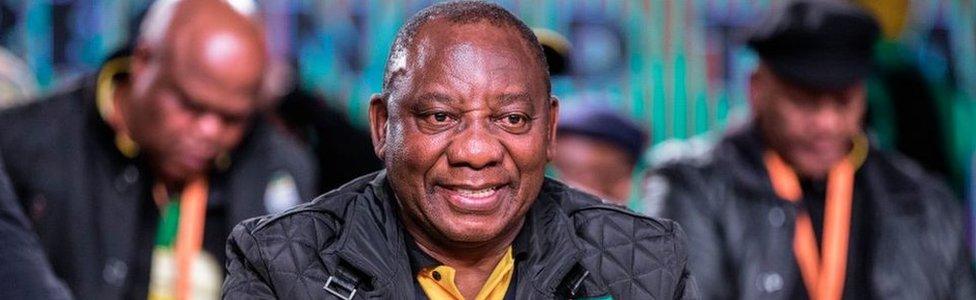

Who is Cyril Ramaphosa?

Currently the deputy president, Mr Ramaphosa is said to have long had his eye on the top job in South African politics.

He worked closely with anti-apartheid icon Nelson Mandela to negotiate an end to minority rule, and to give black people the right to vote for a government of their choice.

Cyril Ramaphosa at a glance:

Cyril Ramaphosa is said to have long held ambitions to be president

Born in Soweto, Johannesburg, in 1952

Detained in 1974 and 1976 for anti-apartheid activities

Launched the National Union of Mineworkers in 1982

Chairman of the National Reception Committee which prepared for Nelson Mandela's release from prison in 1990

Became an MP and chairman of constitutional assembly in 1994

Moved full-time into business in 1997, becoming one of South Africa's richest businessmen

On Lonmin board during 2012 Marikana massacre

Became South Africa's deputy president in 2014

The legend goes that he was so upset about not being chosen by Mr Mandela as his deputy following South Africa's first democratic election in 1994, that he did not attend the presidential inauguration, and refused to take up a post in government.

He stepped out of the political limelight and went into business.

The former trade unionist is now one of the richest politicians in South Africa.

Mr Ramaphosa's track record in the private sector has helped him win the backing of the business community.

He supports the ANC policy of Radical Economic Transformation - putting more of the economy and land in black hands, in an effort to address the legacy of apartheid.

But Mr Ramaphosa has also sought to reassure the business sector, acknowledging the need to "improve investor confidence", and stressing the need for "partnership".

The ANC has battled to fulfil its promise to curb unemployment

This is important because South Africa's economy has been in something of a tail-spin in recent years, with several credit-rating downgrades.

More than a quarter of the population is unemployed, and more than half live in poverty.

The country is one of the most unequal in the world.

Mr Ramaphosa has positioned himself as the man who can turn this around.

He has also spoken out against corruption and so-called "state capture", saying "If corruption holds our economy back, we must solve the problem of corruption. If state capture holds our economy, we must solve the problem of state capture."

Ten phrases which have entered South African speech under Zuma

And he is promising to unify the party, which has been torn apart by bitter rivalry over who should take over from Jacob Zuma as its leader.

What he cannot seem to shake off though, is the shadow of Marikana.

He is tainted by allegations that he pushed for police action against striking miners at the Lonmin mine in 2012.

Thirty-four miners were killed, in what was the worst police shooting since the end of apartheid.

At the time Mr Ramaphosa was a director at Lonmin.

Emails emerged showing he had called for "concomitant action" to be taken against the striking miners, who had been taking part in a violent, wildcat strike.

Families of those killed in the Marikana massacre are demanding justice

The leader of the opposition EFF party, Julius Malema, has repeatedly blamed Mr Ramaphosa for the killings, calling him a "murderer" and vowing not to let the matter rest.

Although Mr Ramaphosa was cleared of any responsibility for the tragedy by a judicial commission, going into an election with the opposition continuing to bring these allegations up is far from ideal.

He is also considered by some to be less in touch with ordinary people than his main rival Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, with a support base that is more affluent.

And Mr Ramaphosa's critics say the events at Marikana show he does not care about poor people.

The choice then for ANC delegates as they prepare to vote, is whether the candidate who seems more likely to steady the markets and rescue the country's troubled economy, is worth the risk of alienating its core support base.

Who is Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma?

She is a medical doctor, and has served in the cabinets of all four of South Africa's post-apartheid presidents.

After serving as Minister of Health, Foreign Affairs, and Home Affairs, she went on to become the chair of the African Union Commission - the first woman to lead the organisation.

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma at a glance:

A leading anti-apartheid activist

Fled South Africa and completed medical training in UK

Met ex-husband Jacob Zuma while working as a doctor in Swaziland

Divorced him in 1998 after 16 years of marriage

Declined offer to take place of her sacked ex-husband as deputy president in 2005

Chair of the African Union commission from 2012 to 2016

Ms Dlamini-Zuma was born in KwaZulu-Natal, the second most populous province in the country, and which will have a big bearing on the outcome of any general election.

Whoever leads the ANC needs to bring votes from this province to guarantee victory.

Although it has been said that Ms Dlamini-Zuma lacks charisma, she is considered by many within the ANC to be someone who gets the job done.

She is credited with having turned around the performance of the Department of Home Affairs.

And the fact that she spent almost two decades in key positions at the heart of government, speaks to her political ability.

Women will make up 50% of delegates at the ANC conference

Ms Dlamini-Zuma has complained bitterly about being referred to as Mr Zuma's ex-wife, pointing out that she was a politician in her own right.

The national broadcaster, SABC, has apologised for doing so, admitting it was "sexist and demeaning".

Her relationship with Mr Zuma is one of her greatest strengths in this race, and her biggest weakness.

Her former husband is a formidable force who can mobilise support for her, particularly at grassroots.

And like him she is considered to be down to earth and more able to connect with voters than some of the other candidates.

But her detractors argue that Mr Zuma has cut a deal with his ex-wife, backing her candidature to avoid being prosecuted for alleged corruption once he steps down.

The Zuma presidency: Scandals and successes

Kinder critics say that as the mother of four of his children, she would find it difficult to make sure he stands trial, even if she wanted to.

For those within the ANC who are tired of being hit by one corruption scandal after another, the elevation of Ms Dlamini-Zuma to the top job would be a perpetuation of the status quo.

And, they fear, that might be an election loser in 2019.

- Published17 June 2024

- Published11 August 2014

- Published4 August 2017

- Published25 September 2017

- Published9 July 2024