What Cyril Ramaphosa's victory means for South Africa

- Published

Despite being an ANC veteran Cyril Ramaphosa has tried hard not to portray himself as a "continuity" candidate

Cyril Ramaphosa was always the frontrunner, but his victory was not the crushing victory that his supporters had been hoping for.

His winning margin was just 179 votes, and his allies failed to secure other key positions at the top of the African National Congress (ANC).

South Africa is now trying to work out whether this amounts to a recipe for further political deadlock, or a new era for the party that has led the country since 1994.

Mr Ramaphosa will now lead the ANC into the 2019, but it is far from clear whether - as had been widely predicted before the vote - he will now be able to act fast to "recall" President Jacob Zuma, and take his place as head of state.

There is precedent for such a move.

Cyril Ramaphosa at a glance:

Born in Soweto, Johannesburg, in 1952

Detained in 1974 and 1976 for anti-apartheid activities

Launched the National Union of Mineworkers in 1982

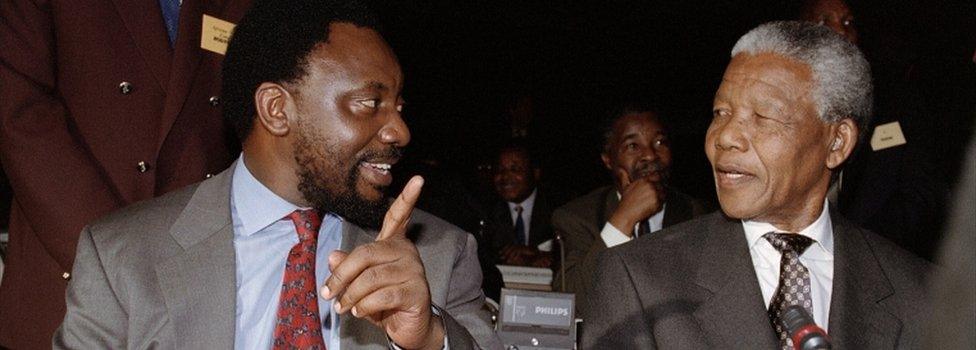

Chairman of the National Reception Committee which prepared for Nelson Mandela's release from prison in 1990

Became an MP and chairman of constitutional assembly in 1994

Moved full-time into business in 1997, becoming one of South Africa's richest businessmen

On Lonmin board during 2012 Marikana massacre

Became South Africa's deputy president in 2014

Elected ANC leader in 2017

It is widely believed that Mr Zuma, who has wrestled with a succession of personal and political scandals, is helping to undermine the ANC's popular support, particularly in urban areas and during his campaign Mr Ramaphosa condemned high-level corruption as "treason", in remarks that seemed aimed at the president.

Much may depend on whether Mr Ramaphosa's supporters manage to secure a solid majority on the National Executive Committee - the ANC's key 80-member decision-making body - in the last hours of this elective conference.

Two provincial leaders, whose careers have also been overshadowed by alleged corruption and who were considered strong backers of President Zuma, secured powerful positions in the party.

Ace Magashule and David Mabuza, the party leaders in the Free State and Mpumalanga, were elected secretary-general and deputy president respectively.

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma campaigned on populist policies

Mr Ramaphosa has a reputation as a shrewd negotiator.

His options may currently be restricted within the ANC, but he remains well placed to become South Africa's next president, a position with formidable constitutional powers to hire and fire.

The political momentum is his to lose.

International investors and ratings agencies are likely to react enthusiastically to Mr Ramaphosa's election, and confidence in the South African economy and currency - which has fluctuated wildly during Mr Zuma's erratic presidency - is sure to rise sharply.

Mr Ramaphosa is an enormously wealthy businessman and has outlined plans to kick-start a stalled economy while tackling entrenched poverty and inequality.

His main rival, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, had, in contrast, alarmed some analysts with her focus on more populist proposals involving targeting the enduring power of white-owned businesses.

Opinion polls suggest that the ANC stands a better chance of shoring up its waning popular support and winning the 2019 elections under Mr Ramaphosa's leadership.

But the divisions - more defined by patronage networks than by policy - within the party will be difficult to paper over, not least after such a rancorous campaign, and the economic and structural challenges facing South Africa remain daunting.

- Published17 June 2024

- Published16 December 2017

- Published16 December 2017

- Published9 July 2024