Esmond Bradley Martin: The daring investigator who took on the ivory poachers

- Published

Esmond Bradley Martin had risked his life to secretly photograph and document illegal sales of ivory and rhino horn

Esmond Bradley Martin, one of the world's leading investigators into the global illegal ivory and rhino horn trade, has been found stabbed to death in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi.

He worked undercover in some of the world's most dangerous and difficult places, photographing and documenting ivory markets, talking to traffickers and calculating black market prices to guide global conservation policy makers.

In the last few years he travelled to China, Vietnam and Laos with collaborator Lucy Vigne, going into places few outsiders would dare to set foot, posing as ivory and rhino horn buyers.

In a Chinese-run casino in Laos, this odd couple would navigate gangsters, drug barons and traffickers of people, guns and wildlife to gather their data.

Their research, funded by Save the Elephants, revealed that Laos has become the fastest-growing ivory market in the world.

They had recently returned from an investigative trip to Myanmar and Mr Martin was writing up that data when he was killed.

Police are investigating the motive for his murder. He died from a knife wound to the neck at his house near Karen, outside Nairobi.

It appears to have been a botched robbery, but police are investigating whether it was linked to his work.

A pair of rhinos follow a park ranger in central Kenya

In a BBC interview in 2016, he said the reason that poaching had increased over the last five years in Africa was due to the mismanagement of many of the areas where elephants live.

"Corruption is probably the single biggest cause of the increase in elephant poaching. Corruption at all levels," he said.

"What has happened over the last few years is that many more Chinese have moved into Africa… There are probably about a million or more expatriate Chinese now working in Africa.

"What we have are these large, open, illegal ivory markets in places like Angola, Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan - and Mozambique, I think - and most of that ivory is being bought by the Chinese."

He helped close down many of the open markets - drawing attention to governments with poor records on wildlife crime.

His work in China is widely credited with helping encourage the ban of domestic ivory trade this year - and the sale of rhino horn in the 1990s.

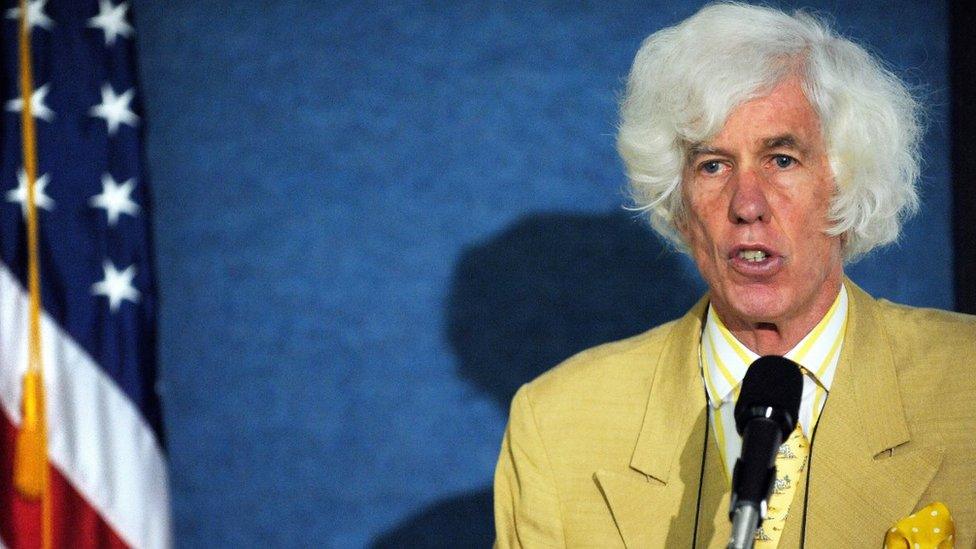

A sharp dresser

A flash of snow-white hair and a sharp suit, often adorned with a colourful handkerchief hanging from the top pocket, would accompany his slightly awkward stride into a room.

Esmond Bradley Martin was quietly spoken, but focused, energetic and utterly engaged in his life's work - collecting data on the illegal trade in wildlife.

Born in New York, he first arrived in Kenya in the 1970s when elephants were being killed for their tusks in huge numbers.

It was then he met the founder of Save the Elephants, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, who says the loss of his friend of 45 years was a terrible blow, both personally and professionally.

"Esmond was one of conservation's great unsung heroes," he says.

"His meticulous work into ivory and rhino horn markets was conducted often in some of the world's most remote and dangerous places and against intensely busy schedules that would have exhausted a man half his age.

"During his 18 years with Save The Elephants, Esmond - alongside his research partners - produced 10 crucial reports into legal and illegal ivory markets."

Conservationists believe that the ivory trade is largely responsible for the world's declining elephant numbers

And his good friend and colleague Dan Stiles remembers how one night in 1999, Mr Martin had persuaded him over dinner to join him on a continental study of African ivory markets.

"It almost killed me - I was lucky to survive," Mr Stiles says, laughing fondly.

"I'd never done anything like it before, and it changed the course of my life."

Friend and colleague Dan Stiles says Esmond Bradley Martin was 'groundbreaking'

Mr Stiles had been working with hunter-gatherer communities, but the two travelled across the African continent searching for any ivory that was for sale, asking how much it cost, meeting ivory carvers, finding out where the ivory came from and identifying the trade routes.

"Esmond was the single person who started quantifying statistics on the ivory and rhino horn trade. People before hadn't really done that. He was really a data man - a facts man.

"With the numbers and the prices it is possible to get a sense of what's going on with the markets and spot trends - he was responsible for that."

Read more:

After 10 weeks travelling the continent, Mr Stiles was exhausted, but Mr Martin was fine.

"He was incredible, he just kept going," says Mr Stiles.

They went on to survey wildlife markets in Asia, Europe and America and produce a series of reports.

Kenyan conservationist Paula Kahumbu has praised Esmond Bradley Martin's integrity

Kenyan conservationist Paula Kahumbu says Mr Martin was unusually generous with his research and shared information for the greater good.

"He was ahead of everyone in terms of identifying how the ivory and rhino horn trade was moving," she says, in reference to some of Mr Martin's most recent research.

"Finding that the ivory trade has moved from China into neighbouring countries will inform how conservationists approach lobbying governments for change."

There is a divide in the conservation community over which approach is better for saving elephants and rhinos: Permitting and regulating the trade to raise money, or totally banning all trade in illegal products to change perceptions.

Park wardens and ranch owners often trim rhinos' horns to prevent poaching

"He was never partisan and always objective, he would just gather all the data and present it. He didn't speak publically for or against trade.

"It's phenomenal that he spent so long - decades - on the issue of trafficking ivory and rhino horn."

The US ambassador to Kenya, Bob Godec, has called the killing of Mr Martin a tragedy for Kenya and the world.

He says he would personally miss his wisdom, insight, and passion, adding: "Esmond was a true giant of conservation and a champion for African elephants and rhinos."

"His extraordinary research had a profound impact and advanced efforts to combat illegal wildlife trafficking across the planet.

"African wildlife has lost a great friend, but Esmond's legacy in conservation will endure for years to come."

- Published6 April 2017

- Published25 October 2017

- Published18 October 2017