My uncle, Nelson Mandela and the Rivonia Trial

- Published

Winnie Mandela leaves court after the verdict. Sixty years later, we can now hear more than 300 hours of the trial

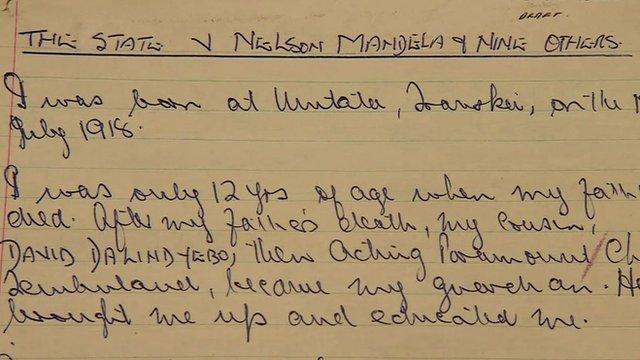

South Africa's Rivonia Trial, which saw Nelson Mandela and other anti-apartheid activists jailed, was a key moment in the country's struggle for freedom. Now, more than 50 years later, all of the roughly 300 hours of proceedings are available to listen to for the first time. The BBC's Gavin Fischer, who has a personal connection to the trial, looks at what the tapes can reveal.

The Rivonia Trial, lasting from October 1963 to June 1964, has been well documented as a pivotal point in the fight against the white minority government in South Africa.

It brought Nelson Mandela to the world stage. His famous speech from the dock, declaring that freedom and equality was "an ideal for which I am prepared to die", became a rallying cry for black people under the apartheid regime, and set the young lawyer on a path to become the country's first democratically elected president 30 years later.

It could have been very different.

Mandela and his co-accused faced the death penalty for acts of sabotage against the state.

It was my great-uncle, Bram Fischer, who led their defence team, and was part of saving their lives. He took great risks in getting involved, as he was also an anti-apartheid activist who could himself have been in the dock at the Rivonia Trial.

More myth than man to me

In fact, just a few years later, he too would be arrested and sentenced to life in prison. Seen as a traitor to his own white, Afrikaner people, he was badly mistreated and died while still in custody in 1975, before I was born.

But by being given access to the newly digitised tapes from the Rivonia Trial, I have been able to go back to a time before tragedy overtook Bram's life.

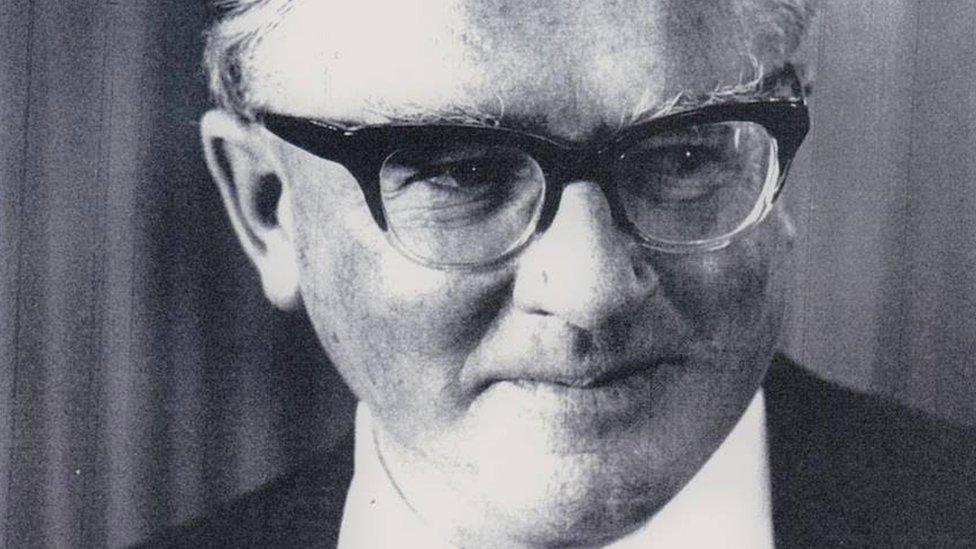

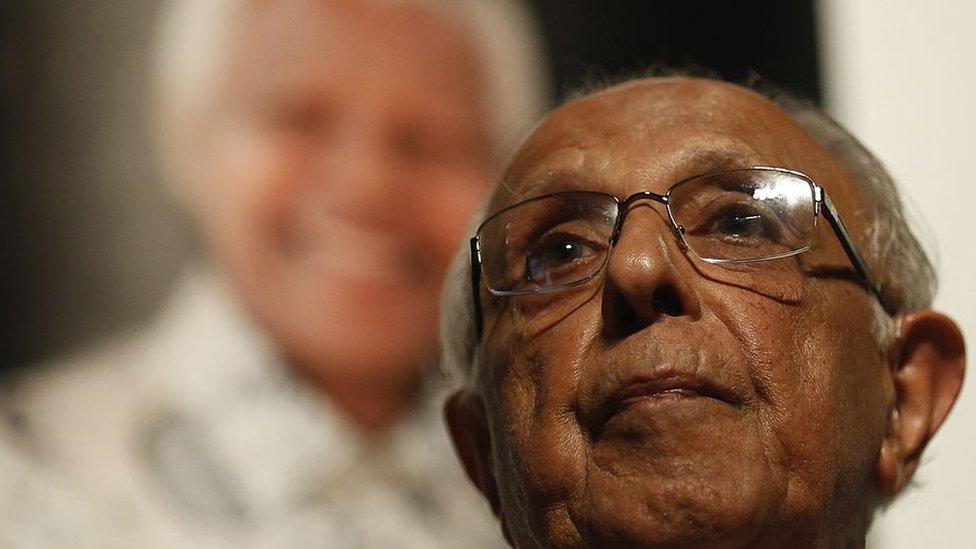

Bram Fischer, also an anti-apartheid activist, represented the men at trial

It's been my first chance to hear him speak. Polite to all he addresses, his calm tones are shot through with a seam of fierce authority. Eyes shut and headphones on, I listen. For the first time my great uncle, who has been more myth than man to me, starts to become real.

The Rivonia Trial is itself now steeped in a kind of myth, part of the great story of South Africa's journey to freedom.

The new recordings give the opportunity to hear some of the journey's most famous moments.

There's the searing power of Mandela's speech, Walter Sisulu's impressive philosophical outwitting of the prosecutor, the defiant humour of Ahmed Kathrada and Denis Goldberg and Elias Motsoaledi's humble but striking detailing of the life of black people in South Africa:

"I did what I did because I wanted to help my people in the struggle for equal rights. I felt very strongly about the laws which discriminated against my people and which caused poverty, ill health and misery for which they suffer," he told the court.

Immersing myself in the recordings, I've been able to forget the historical significance of these moments and simply be overawed by them. Not knowing what the future held, these men didn't beg for clemency or deny their actions, they used the trial to highlight the injustice being perpetrated by the government. To hear them speak is a privilege.

I have also found myself getting lost in some of the trial's more mundane moments: the background chatter, the scraping of chairs, the thuds and silences as the recording equipment is adjusted.

I revel in it all as the sounds swell and fall, pulling me back to that time.

Then, from the midst of the crackle and hiss of the recordings, come moments of startling resonance I never knew existed and which are rarely documented in the story of the Rivonia Trial.

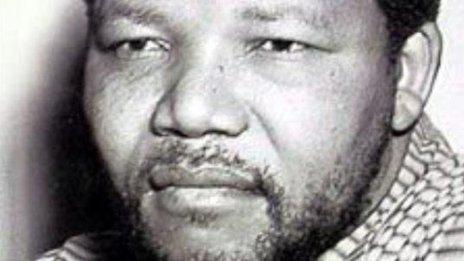

Nelson Mandela: "It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die"

Thomas Mashifane was a state witness, tortured into giving evidence against the accused. He had worked at a farm called Liliesleaf in Johannesburg, which Mandela and others had used as a hideout.

He knew nothing of their activities, and his testimony is filled with innocuous detail, irrelevant to the case.

Yet, at its end, he speaks up, unprompted, about being beaten and humiliated by the police. I can't breathe for the horror of it.

I want to shrink from what white people did back then; but I also want to run over and hug him for forcing the court to hear what really happened. When I get to that moment, I have to take my headphones off, I just cannot sit in that courtroom any more.

Weeks later, I meet Mr Mashifane's daughter Elizabeth. She's kind, though her manner is distant, hardened in preparation for reliving her father's ordeal.

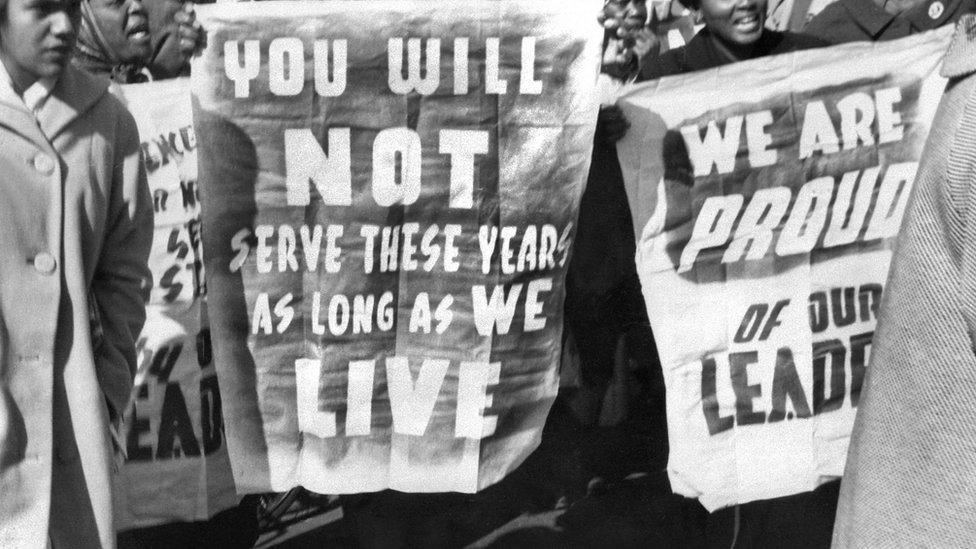

Protesters outside the court in Johannesburg

But as I play her the tape, this strength seems to drain away. It's the first time she has ever heard this testimony.

"It makes me feel like it happened yesterday," she tells me.

As she listens, Elizabeth looks away from me, lost in her father's words.

I try to fill the silence that follows, searching for something - anything - positive to say. I end up asking if she is proud of the fact that he spoke up. For a moment, her eyes turn back to me.

"But did it make any difference?" she asks.

No answer is necessary. Turning away again, she says more quietly: "None of them were treated like humans."

Thwadi Makena still feels the impact of the trial to this day

Thwadi Makena was also a labourer at Liliesleaf, and the only one left alive today. When I meet him, he strikes me as a quiet, humble man.

On the tapes, he recounts being beaten by the apartheid police: "They told me to undress, I did undress. They then were in a group… and told me to run round the table and each one I passed either kicked me or struck me with fists.

"My right ear is still suffering the effects, and my one front tooth in my top jaw is still loose. I just wanted to know why I was assaulted like that, when I was not committing any offence."

Yet, as I play him the recording, Mr Makena's thin face comes alive and he chuckles with delight.

"I feel very excited to hear my voice after so many years. It's just so amazing - I can't believe it," he tells me.

As with most of those I have spoken to, recalling details of the case turns Mr Makena's mood more sombre. He was held by police, made to feel like a criminal and says the impact it had remains to this day.

"I tend to feel they might come back and say some new information has been revealed and [I] need to come and make some confession," he says. "That fear has always been there."

Not an end, but a beginning

While the recordings contain details which can bring back difficult memories, in playing them to those closest to the trial, I have found all have appreciated the chance to hear voices they thought lost forever.

It is clear even short snippets of tape can help reclaim these stories from the dehumanising mass of the apartheid state.

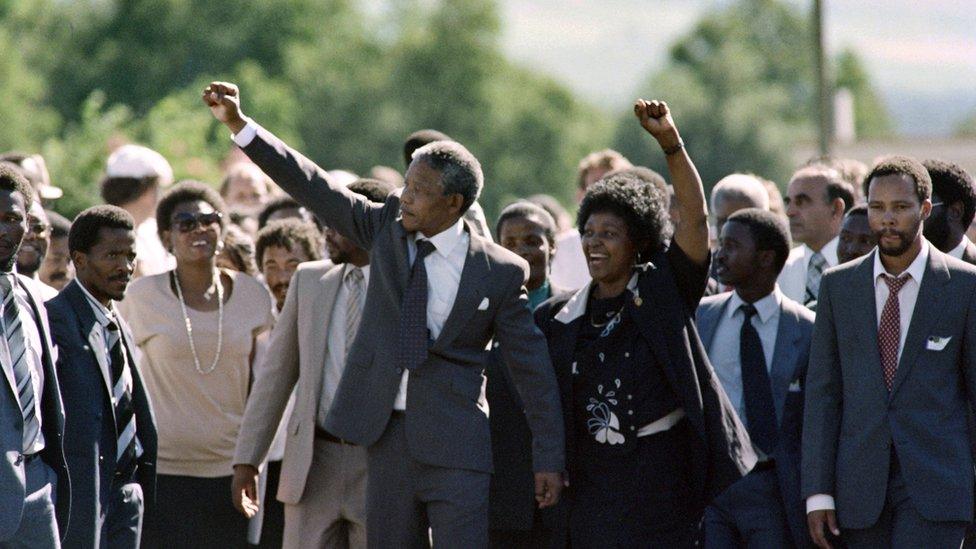

Nelson Mandela spent 27 years in prison after the trial, before being freed in 1990

Laws may have changed since democracy was won, but grinding structural injustice remains a reality for so many South Africans. I too often lose these individuals' stories in an effort to find sense in the state of this country.

The more tales of poverty I hear, the less I understand the cause or the solution. So these tapes have a lesson for me: don't become numb. Listening is at least a start.

There is no chance to hear the verdicts of the trial. Those tapes haven't been found.

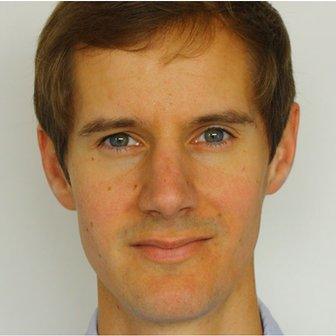

Gavin Fischer: "The more I hear of poverty, the less I understand"

Maybe we'll never hear the moments when the judge showed what little mercy he could find, in the law and in himself, sentencing all the accused to life in prison.

Life, not death. Not an end, but a beginning. Maybe even the beginning of a new chapter in the country's history.

But as the audio plays, that story is still in the future. The tapes fuzz and hiss and you can sense the tension of what might come to pass.

In these moments, the Rivonia Trial feels not so much of the past, but of the present. As I listen, my great uncle is still alive and the people around me suffer, fight and survive, not knowing what their future holds.

- Published28 March 2017

- Published7 December 2013

- Published8 December 2013

- Published12 October 2013