The 'baby warehouses' which cater for Israel's unwanted migrants

- Published

Some 37,000 African migrants are currently in a state of limbo in Israel, unsure how much longer they can stay in the country. The government wants them to leave but its original plan to deport some of them was struck down by the courts. Then Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu changed his mind on a deal with the UN just hours after it was agreed. BBC Newsday's Nomia Iqbal went to meet some of the migrants.

The small cramped apartment in south Tel Aviv contains the following: three rooms, one toilet, one radio playing American pop songs, one Nigerian woman stirring a pot of food, another woman sitting on a chair looking at rows of cots, and 20 small children.

The windows are open, but these little boys and girls are not to allowed to leave. A locked gate keeps them inside the flat.

The older ones run to us with outstretched arms, beaming: "Shalom."

Their boundless enthusiasm shows they aren't used to visitors.

"It is very hard work keeping them quiet and focused," says the woman in the kitchen.

Dangerous

This apartment is one of around 90 "baby warehouses" - unlicensed places which offer a cheap child-minding service to thousands of African migrants who cram into this small part of Tel Aviv.

We have been allowed as long as we don't reveal its exact whereabouts, take any photos once we're inside or record anyone on tape.

No loving parent, it is fair to say, would choose to leave their child here if there was another choice. In 2015, five babies died in informal "nurseries" due to negligence or inadequate care.

But Sophia, who is from the charity Elifelet, which helps refugee children and wants to create safe nurseries, knows they have little choice - especially with the government's increasingly hostile tone to the people it deems illegal immigrants.

"Everybody is worried about deportation so parents are working even longer hours to earn money," she tells us. "They need to leave their babies somewhere cheap."

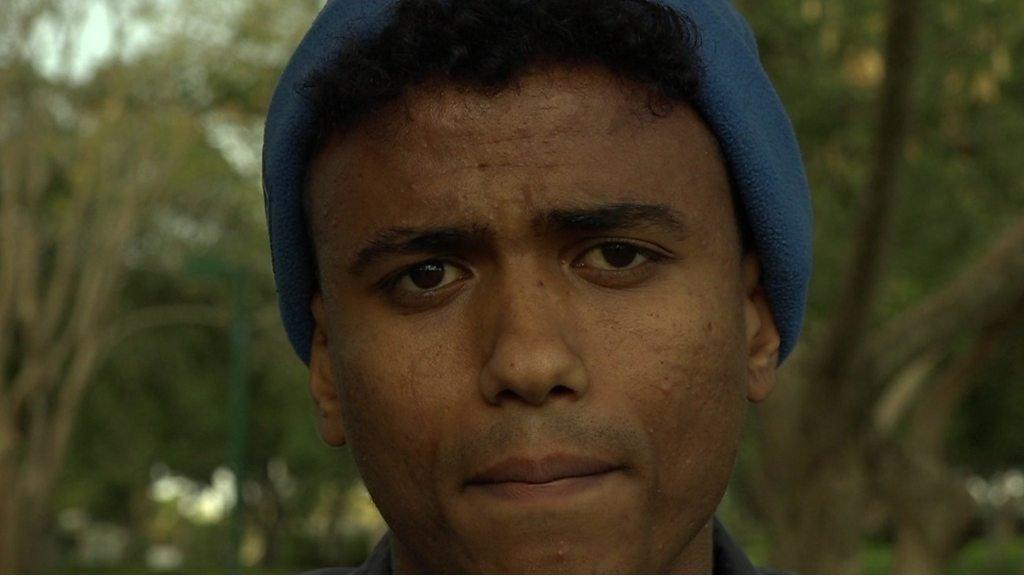

The Israeli government wants to deport thousands of migrants

The vast majority of the migrants in this overcrowded corner of Tel Aviv are from Eritrea and Sudan, arriving on foot in Israel between 2006 and 2012.

Many hoped to find asylum: more than 15,000 Sudanese and Eritreans applied for it between 2013 and 2017. So far, just 12 applications have been accepted. In comparison, human rights campaign group Amnesty International says the European Union accepted more than 92% of Eritrean asylum applications in 2016.

And now Israel wants those it sees as economic migrants out. In January, it offered the migrants $3,500 (£2,510) and a plane ticket to leave Israel voluntarily by the end of March.

Those who refused faced detention and subsequent expulsion.

"We are taking action against illegal immigrants who come here for work purposes," Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said earlier this year.

"Israel will continue to be a shelter for true refugees and will eject illegal infiltrators."

Although the government's plans are on hold, Mr Netanyahu still insists that they must go.

So the parents arriving to collect their little ones from the apartment are worried.

A mother, originally from Eritrea, appears to pick up her six-month-old daughter, who has been lying silently in the cot clutching an empty milk bottle.

Hatikva Market, in south Tel Aviv - the area where most African migrants live in Israel

The mother - who we'll call Faven - doesn't communicate much with the two minders because of language differences.

"It's been a long day," she says by way of explanation as she picks her quiet daughter up. "I've been cleaning since very early to make some money so I can look after her."

For Faven, there is no choice.

But these places are seen as a danger by human rights groups like Elifielt, with consequences which will stay with the children long after they have left.

"It would not be an exaggeration to say that the children leave with post-traumatic stress and delayed learning," Sophia says.

The Eritrean runner fearing deportation from Israel

Outside, there is little immediately obvious sympathy to these families' plight.

"These Africans are not my problem!" shouts one elderly taxi driver in Neve Shaanan, a working-class part of south Tel Aviv where most of the migrants are clustered.

Here, there is much support for Mr Netanyahu's stance, with national polls suggesting that his approval ratings are going up.

In nearby Hatikva market, 31-year-old Zion runs a market stall. He denies that racism is behind the feeling that there are too many migrants in the area.

"Look, they are nice people, but I don't believe they are refugees," he tells us. "They're all living in one place and it's like they're replacing us."

He says those fighting for the right of migrants to stay in Israel have never shown as much support for his community - Mizrahi Jews who moved to Israel from Arab countries.

But he says deporting people wouldn't feel right and is "very angry" at the government "for creating the problem in the first place".

Thousands turned out to protest at the Israeli government's plans

The 25,000 people who gathered in Tel Aviv's Rabin Square recently to protest against the deportations are also angry at the government, albeit for different reasons.

Rabbi Susan Silverman, the co-founder of Miklat Israel, a sanctuary project which was set up to help absorb refugees into communities around the country, believes the government's policy goes against Jewish teaching.

"We have a clear religious mandate to welcome the stranger," she says. "But also we have a history of having needed people to take risks for us, to open their homes for us, to help us and we are rejecting that legacy."

Following a legal challenge by a group of Eritrean and Sudanese migrants, the deportation plan was suspended by Israel's supreme court.

The UN then proposed a deal which would see thousands of African migrants sent to Western nations, while others would be granted residency in Israel.

Prime Minister Netanyahu has now scrapped this scheme but says: "Despite legal restraints and international difficulties that are piling up, we will continue to act with determination to explore all of the options at our disposal to remove the infiltrators."

So it remains an uncertain time for parents like Faven who use the illegal nurseries.

As she picks up her baby ready to leave the flat, she wearily looks up and says: "I'm glad she is safe and okay - today."

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published2 January 2018

- Published14 March 2018

- Published8 June 2016