Why Kenya hopes blockchain can end land grabbing

- Published

People put up signs and notices on their properties to ward off land grabbers

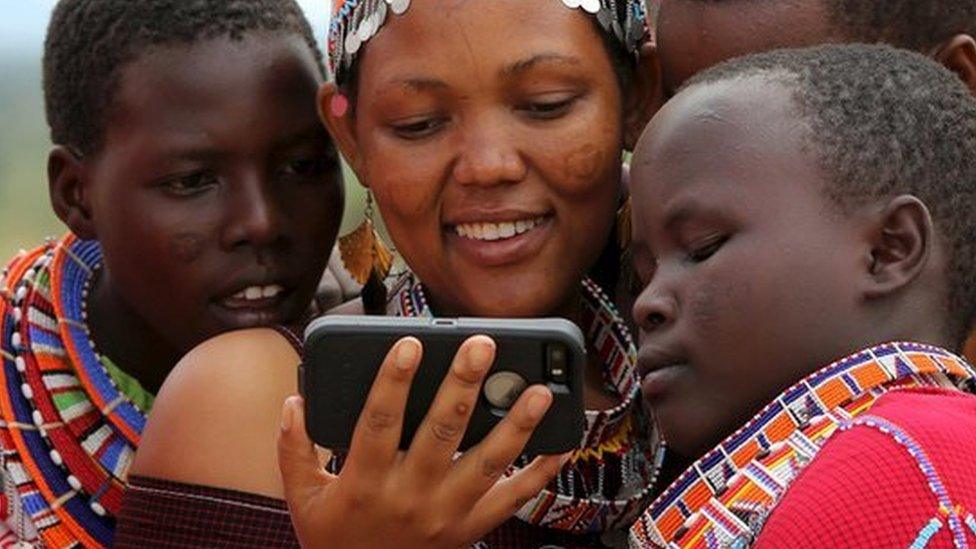

Kenya sees itself as a technology giant in Africa and has embraced the nickname "Silicon Savannah" - now it has set up a special team to look into how to take advantage of the latest technologies such as Artificial Intelligence and blockchain.

"We missed the internet wave, caught up with mobile technology... blockchain is the next wave - and we must be part of it," the team's chairman, Bitange Ndemo, told the BBC.

A blockchain is a shared database with a provable, auditable and verifiable record of all changes. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the use of computer systems to perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence.

Information Minister Joseph Mucheru, the man who the team will report to, says that, among other uses, blockchain could help organise land records stored by the government, which are a constant source of frustration for people who want to buy, sell or verify information about land.

Possessing a title deed in Kenya does not necessarily guarantee ownership because fraudsters in cahoots with land officials have been known to change land records.

In fact, to buttress their land ownership claims beyond having a certificate, many Kenyans paint "This Land Is Not For Sale" on their property to warn off potential land grabbers.

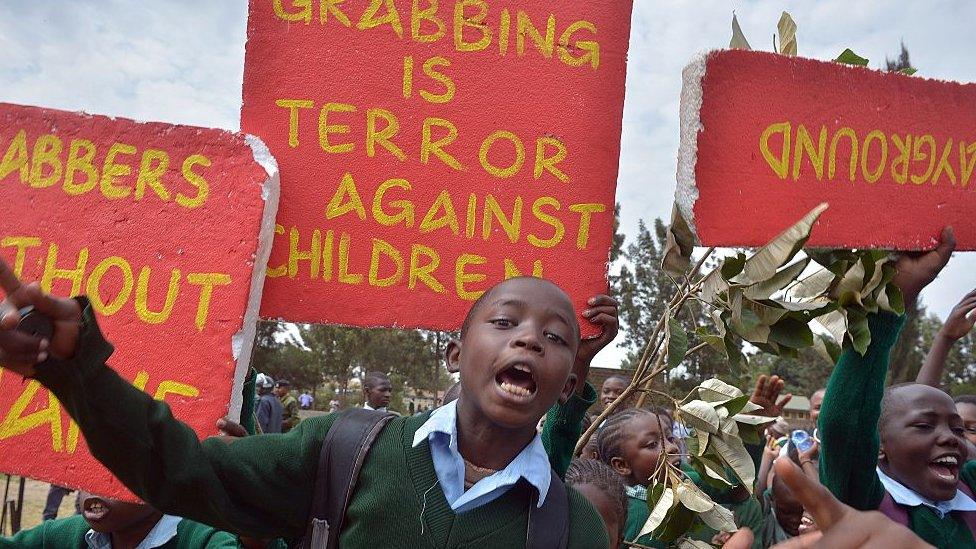

School children were tear-gassed while protesting against attempts to grab their playground

In 2015, Kenyans witnessed a sad spectacle when pupils of a public primary school in the capital, Nairobi, were tear-gassed while protesting against attempts by a top hotel to grab the school's playground. Reports said that the school did not have a title deed.

The confrontation led activists to form the Shule Yangu Alliance - a pressure group - whose aim, it says, is to have 10,000 public schools issued with title deeds and fences built around 5,000 schools.

At the time, an official from the land commission advised all state institutions, which are usually easy targets for land grabbers, to get title deeds but also to put up fences.

Lack of trust

If land records were housed in an immutable blockchain, proponents say, it would reassure people that their records are intact and that the title deeds they own match government records.

According to Mr Mucheru, the platform provides "security, efficiency and transparency".

Caine Wanjau, the technology officer at Twiga Foods, a Kenya-based food distribution company, says: "In a relationship where two parties don't trust each other, then blockchain makes sense."

The company recently announced a partnership with IBM Research to create digital profiles of informal small-scale traders - to be stored in a blockchain - to help them access credit.

"Seventy percent of Kenyans work in the agriculture sector but only 2% get credit from banks. We want to create an immutable - trustworthy - database of the vendors and suppliers we deal with to help them, and banks to have access to information they can use to negotiate credit," Mr Wanjau adds.

Can technology create enough jobs for Kenya?

Population 49m

20% of population are aged 15-24

One million young people join workforce every year

83% of 13m labour force in the informal sector

Unemployment rate 7%

$5bn investment to build new technology city

Sources: World Bank, KNBS, ICT Board

June Okal, from technology site Techweez, says that the conversation should not be limited to the technology but should also include people's privacy and data protection.

This is a big concern considering the country was caught up in the scandal involving British company Cambridge Analytica, which is accused of using people's personal data taken from Facebook, without permission, for its controversial micro-targeting election campaign strategy.

Kenya's constitution guarantees the right to privacy but its parliament is yet to pass a law that gives unambiguous protection.

About 80% of Kenyan workers are in the informal sector

Mr Mucheru, who left tech giant Google to join the government, says that the absence of laws should be seen as an opportunity to spur innovation.

He has, for instance, been a proponent of trading in Bitcoin - the highly volatile and unregulated cryptocurrency which operates on a blockchain platform - even though the country's central bank governor has described it as a ponzi scheme.

Blockchain is also being touted as a possible solution to various challenges in other countries in Africa.

Petrol pumps are still manned instead of being computerised

In South Africa, it is being proposed as a tool to fight corruption, external.

Mining giant De Beers also plans to use the platform to provide a foolproof record of the source of diamonds to ensure they are not from conflict zones , externalwhere gems could be used to finance violence.

The decade-old concept is however not a silver bullet - its vulnerability was recently exposed after hackers accessed $400m (£253m) worth of digital coins from a Japanese crypto-currency. , external

Some people have also questioned whether blockchain is the technological game-changer its proponents are selling it to be. Financial expert Kai Stinchcombe argues: "It's true that tampering with data stored on a blockchain is hard, but it's false that blockchain is a good way to create data that has integrity." , external

'World's freelancing headquarters'

Mr Mucheru dismisses concerns that Kenya has other pressing needs to deal with, saying that not investing in the new technologies now would only leave the country at a disadvantage.

"We already have people who are writing software for autonomous drones and experimenting with Artificial Intelligence and that number will only grow," he says.

"We want to be the freelancing headquarters of the world," he adds.

Despite his optimism, there are signs everywhere that it will take a long time for Kenya to fully feel the impact of AI-powered robots in their daily lives.

For example, hundreds of Kenyans still work as pump attendants at petrol stations across the country - a job that could easily be automated.

Mr Mucheru insists that investing in AI technology will create new opportunities, even though he admits that it will kill other jobs.

Entrepreneurs like Mary Mwangi, from Data Integrated Limited, remain optimistic about the future.

The company launched a device called Mobitill which aims to bring "financial accountability and security" to Kenya's notoriously anarchic public buses known as matatus.

A Kenyan start-up aims to use AI to track mini-buses to help stop ticketing fraud

"The device uses sensors to track the bus and collects data on passenger numbers and ticketing to ensure full accountability," Ms Mwangi says.

Even though the device was built by local software developers, she says that there are not enough engineers in the country to fully power an AI industry. "But we have a lot of upcoming talent," she adds.

The talent will be needed to fill thousands of skilled jobs expected to be created after the completion of a $5bn (£3bn) technology city called Konza City, external, which is part of Kenya's ambitious development plan known as Vision 2030.

The technology hub will sit on 5,000 acres of land and aims to be the centre of innovation which will attract top technology companies to set up shop.

If Konza City turns out as planned, Kenya will really live up to its title of the "Silicon Savannah".

- Published4 May 2018

- Published3 January 2018