Letter from Africa: Why I loved Winnie Mandela, warts and all

- Published

In our series of letters from African writers, Ghanaian journalist Elizabeth Ohene shares her admiration for Winnie Madikizela-Mandela as South Africa holds a memorial service for the anti-apartheid campaigner.

Quite often when you meet in person people you have known on the radio, newspapers and television they turn out to be not quite what you had imagined them to be.

There was no such difficulty the first time I met Winnie Mandela in the flesh.

She was everything I imagined from reading about her, hearing her on the radio and watching her on television.

She wasn't bigger or smaller than I thought, she simply occupied the space with her presence.

She was as strikingly beautiful as I had surmised and her voice was at once imperious and empathic.

Her clothes were distinctive and you got the impression she made an effort each time she stepped out.

This impression about her at this first meeting was reinforced at later, more frequent and close meetings.

More on Winnie Madikizela-Mandela:

Our first meeting was in the night and the circumstances were somewhat chaotic.

She had arrived at the home of Albertina Sisulu, the other "mother of the nation", the night Walter Sisulu and five other African National Congress (ANC) long-time prisoners were released.

She did not enter the house but stayed with the gathering crowd under the trees in the garden.

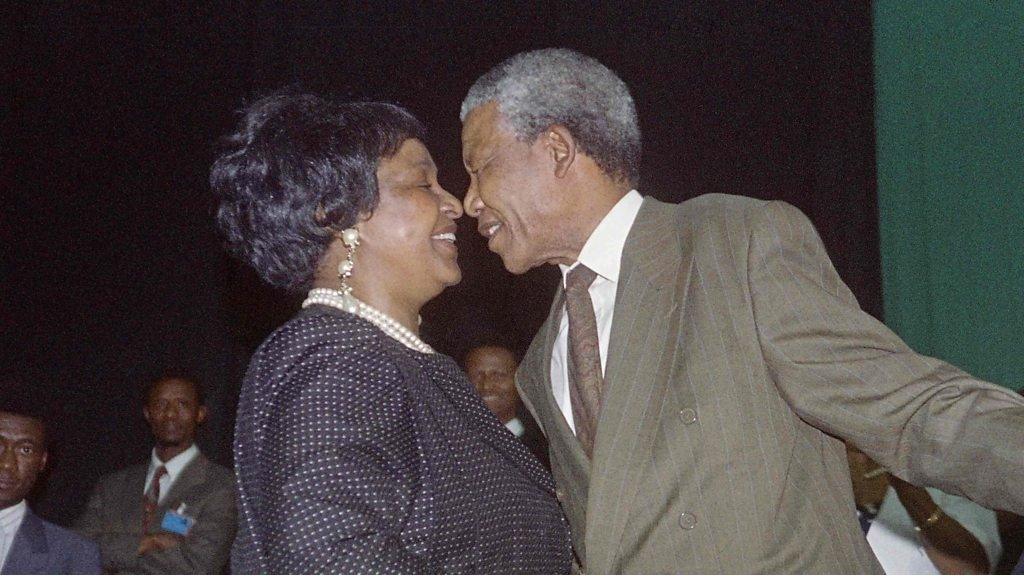

Winnie Mandela stood by her husband's side on his release from prison in February 1990

Soon Mrs Mandela was surrounded by journalists and we all wanted to know if she was disappointed that her husband Nelson Mandela was not among those released.

The important thing that day, she said, was to celebrate the homecoming of Mr Sisulu and the others, which she said marked the start of the final march to liberation.

As for her husband - and she stopped for emphasis: "He will come home."

Elizabeth Ohene:

"The world was sharply divided into those who loved her and those who hated her with a passion that was a wonder to behold"

Since this was October 1989, it meant almost all the defining incidents of Mrs Mandela's life had already taken place.

The arrests, banishment, torture, imprisonment, the notorious football club, her battles with the apartheid government - all were ongoing.

The world was sharply divided into those who loved her and those who hated her with a passion that was a wonder to behold.

I had long decided before I came face-to-face with her that I was a Winnie Mandela lover and supporter.

'Jail keeps your reputation intact'

I had worked out for myself that of the three strands of anti-apartheid activists, those who went to jail and those who went into exile were luckier than those who stayed and had to brave the daily existence under apartheid.

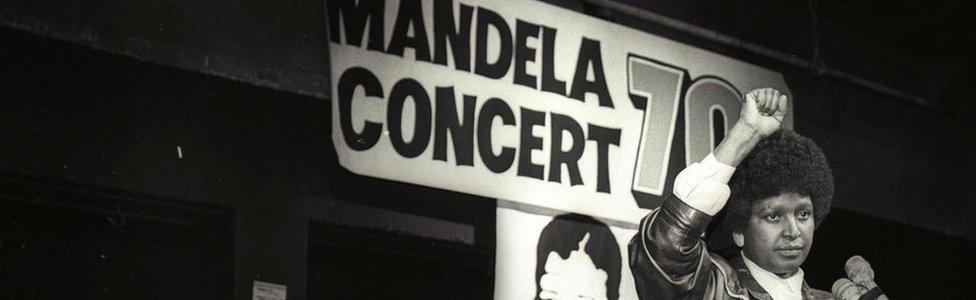

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela was dubbed the "Mother of the Nation" for her anti-apartheid work

Nothing will touch your reputation whilst in jail, no chance of committing adultery for example.

Nor were you likely, whilst in exile, to have to distinguish who is genuine and who is fake among the youths running into your home to seek shelter from apartheid police, or cope with the violence of the townships.

'A survivor'

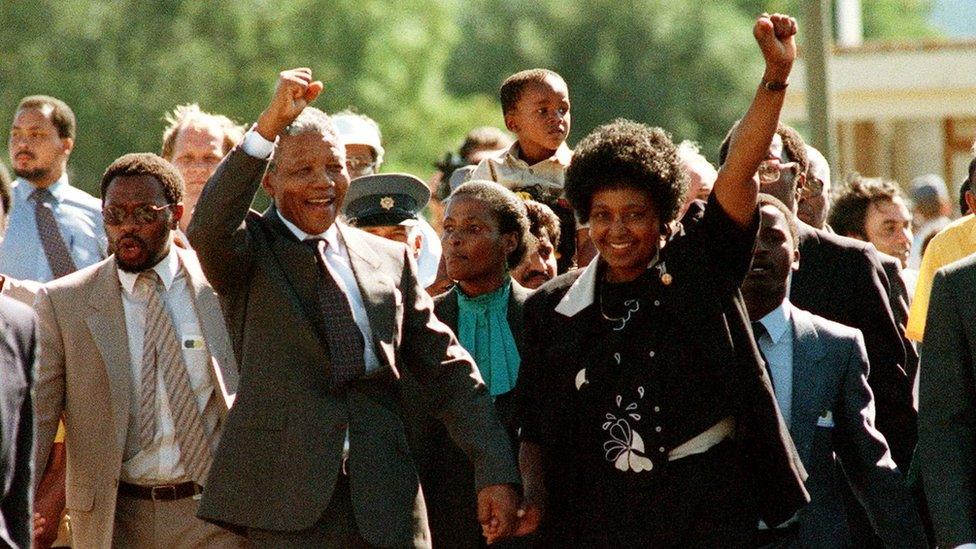

The day Nelson Mandela announced that he was separating from Winnie, I was among the assembled journalists he addressed.

It was April 1992, two years after his release from prison and two years before he became South Africa's first democratically elected president.

He looked very distressed and pleaded not to be asked any questions after making his statement.

The room full of hardened journalists allowed him to leave without asking any questions.

Many of my colleagues that day, made up largely of foreign correspondents, would have asked him why he had tolerated her for so long.

It is safe to say there were not many Winnie Mandela lovers in that group.

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela died last week at the age of 81

I wanted to ask Mr Mandela that day if he thought there was anything that his wife had done which could not be forgiven.

The Winnie that he had left behind after four years of marriage and two little girls to brave, by herself, the might of apartheid South Africa.

The Winnie who kept his name alive and the movement relevant for 27 years, indeed the Winnie who became the movement.

The Winnie who had to be constantly on her guard against infiltrators.

The Winnie they couldn't break no matter how hard they tried.

I didn't get to ask my question but Winnie Mandela did not need me to ask such questions, she survived it all and with such grace.

She will doubtless have a well-deserved rest.

I loved her, warts and all.

More Letters from Africa

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published2 April 2018

- Published2 April 2018

- Published7 April 2018

- Published2 April 2018