Reality Check: Are young Nigerians working hard enough?

- Published

As the president of a democratic country, suggesting the bulk of your electorate is lazy is not usually a good idea and doing so at an international business forum, even less so.

And that is what a lot of Nigerians thought about comments made by their president, Muhammadu Buhari, on a visit to London last week.

Speaking on a panel during the Commonwealth Business Forum, President Buhari said that "a lot of" Nigerian youths claim "they should sit and do nothing" but expect to get "housing, healthcare and education free".

Unsurprisingly social media erupted and the hashtag #LazyNigerianYouths was born.

In a statement soon afterwards, the president defended his words. His media aide quite rightly pointed out that the president never used the word lazy. But that didn't do much to quell the angry masses online.

One Twitter user said: "I am a 2nd class upper graduate of chemistry science from university of Lagos, I am now a shoe maker cos I couldn't get a job, I am not lazy, I am not lazy I am not lazy #LazyNigerianYouths".

President Buhari met with British Prime Minister Theresa May during the week of the Commonwealth summit.

To get to the bottom of this heated debate, BBC Reality Check looks at the stats and asks - in a country famous for its hustle - how much are young Nigerians contributing to the economy?

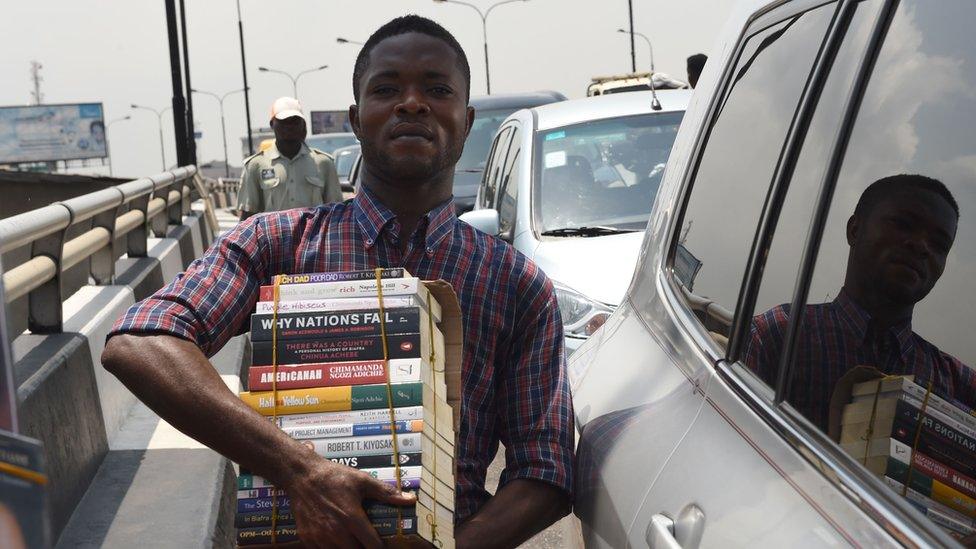

Ask a Nigerian what they do for a living and you're likely to get a minimum of two answers, three is normal - four, not beyond the realms of possibility. And, as many of these #LazyNigerianYouths posts demonstrate, when a salaried job is out of the question Nigerians can find creative ways to make money.

As the president said in his speech, 60% of Nigeria's population is under 30 - that's roughly 107 million people.

A lot of them are still children but a huge chunk are of working age and yet can't get a job.

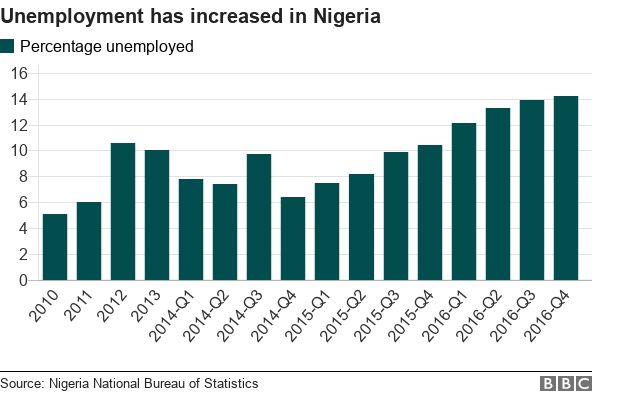

Unemployment in Nigeria almost tripled from 2014 to 2017 from 6.4% to 18%, according to the Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics. It increased at roughly the same rate for 15 to 34-year-olds as it did for older workers.

But here's the crucial difference - from 2014 to 2017 Nigeria's older labour force increased by 3.9m, its younger workforce increased by 8.2m.

Meanwhile, Nigeria's economy, which relies on exports of oil, tanked because of the slump in the global price of oil. It would make sense that most of these young people would struggle to find jobs and they did.

Even though there was a recession, in both age groups the number of people who found work increased by about one million. (Nigeria came out of recession in September 2017).

So despite their lack of experience in an increasingly competitive market, just as many young people as older people were able to hold on to their jobs or even to find jobs.

Cue cheers from Nigerian youth everywhere. But it may not all be good news.

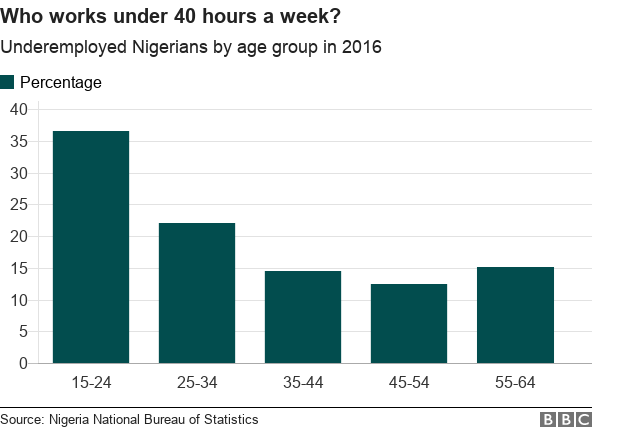

It's important here to look at underemployment - those who work fewer than 40 hours a week or are working in jobs where their pay doesn't match their qualifications.

A total of 40% of Nigeria's 80 million-strong workforce is "unemployed or underemployed".

In the 15 to 34 age bracket this is much higher, more than half (52%) work less than a 40-hour week. That means 22.6 million young people are struggling to get by.

An interesting stat from 2004, in a report by National Transfer Accounts, which studies populations and economic change and is based at Berkley University in California, said that Nigerians spent more than they earned until they were 32. That means, despite working, they didn't earn enough to get by.

That was 14 years ago, we don't know whether the same or worse is true in today's economy. But inflation has rocketed over the past three years, only recently slowing down, while wages haven't risen, so it's likely young people are facing a similar challenge and relying on older relatives for support.

It's also likely that a lot of young people are working in the informal economy, which is huge. The IMF says the informal economy makes up more than 60% of the country's GDP - the highest in Sub-Saharan Africa. But it's also mostly low-skilled, low-paid work, with inferior working conditions and zero benefits.

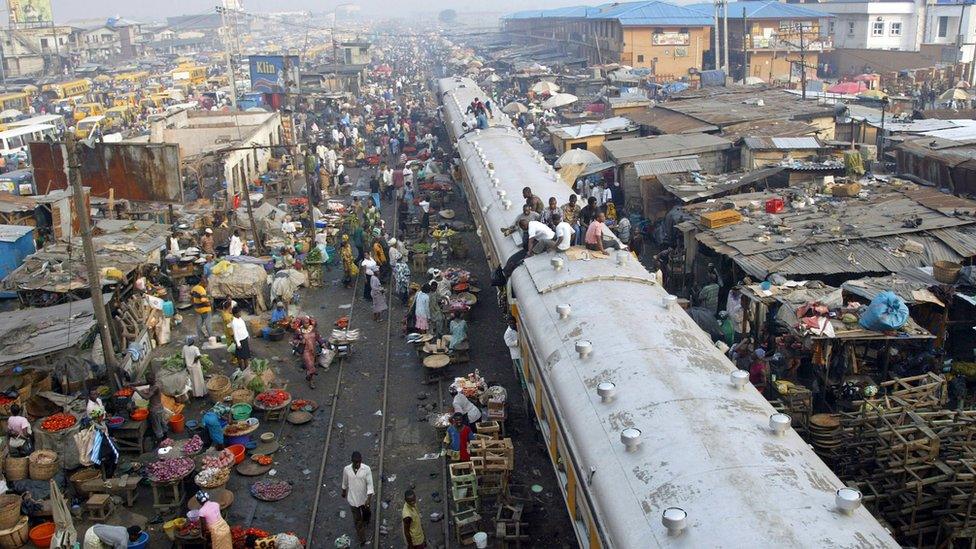

Lagos could be the hustle capital of the world, epitomised by the street hawkers in every traffic jam, where hundreds of young people carry boxes of plantain chips, biscuits, water, even kitchen appliances or enormous cuddly toys.

They weave in and out of traffic jams, breaking suddenly into a fierce run to secure a sale, abandoning sandals in their wake as they try to keep up with drivers who refuse to lose their place in the queue.

Despite their doggedness, these young people aren't earning as much, or contributing as much to the economy as those working in say, banks or phone shops. And they definitely aren't paying tax.

But then, the argument goes, why should they? There is something even deeper that this debate has brought to the surface - Nigeria's struggling public education system.

You may also be interested in:

Unicef puts the number of Nigerian children out of school at 10.5 million,, external the highest in the world - by size, not proportionally. And the quality of public education has slipped so low that it has become a last resort for many families.

Three-quarters of schools in Lagos are private, according to the World Bank. On top of that, anyone who can afford it, including the president himself, sends their children to school abroad. And that's why #LazyNigerianYouths is being used to celebrate individual achievement despite the odds set against it.

Nigeria is one of the fastest growing countries on the planet, set to surpass India and the US by 2050, so the electorate is only getting younger.

This presidential incumbent - who will be 76 by the time elections come next February - would be wise to start thinking about how he addresses them.

- Published25 April 2018

- Published9 April 2018

- Published9 March 2018