Crossing Divides: Can Nigeria's new tin mine heal ancient wounds?

- Published

Farmers and herders now work together in the new mine

Environmental changes have caused tensions between settled farmers and nomadic herders in Nigeria to flare into ethnic conflict.

But could working together to serve the demands of modern consumers heal ancient ethnic rifts, asks BBC World Service correspondent Stephanie Hegarty.

As the sun sets over the stony hills of Jos, long-horn cows climb awkwardly down into a rocky gorge. They shimmy their bony shoulders, navigating a path worn into the stone over decades of this same grazing ritual.

In this picture-postcard of serenity it's hard to imagine that until recently this community in central Nigeria was at war with itself.

It's one of the world's most ancient conflicts.

Across the northern part of Africa the desert is creeping outwards, swallowing up fertile green land and pushing Fulani herdsmen into conflict with farmers over grazing rights.

'We didn't believe we could work together'

"My people would kill them," says Henry Botson, a man in his 30s from the Berom tribe. He lives in Barkin Ladi, Plateau state, where in 2011 a brutal conflict flared between his people and their neighbours.

"And if we passed into their own territory they would kill my people."

Mr Botson is short and stocky, wearing a green beret with a miniature AK-47 assault rifle on a silver chain around his neck.

And this is part of the problem. Since the collapse of Libya, guns have flooded into West Africa, most of them ending up in Nigeria.

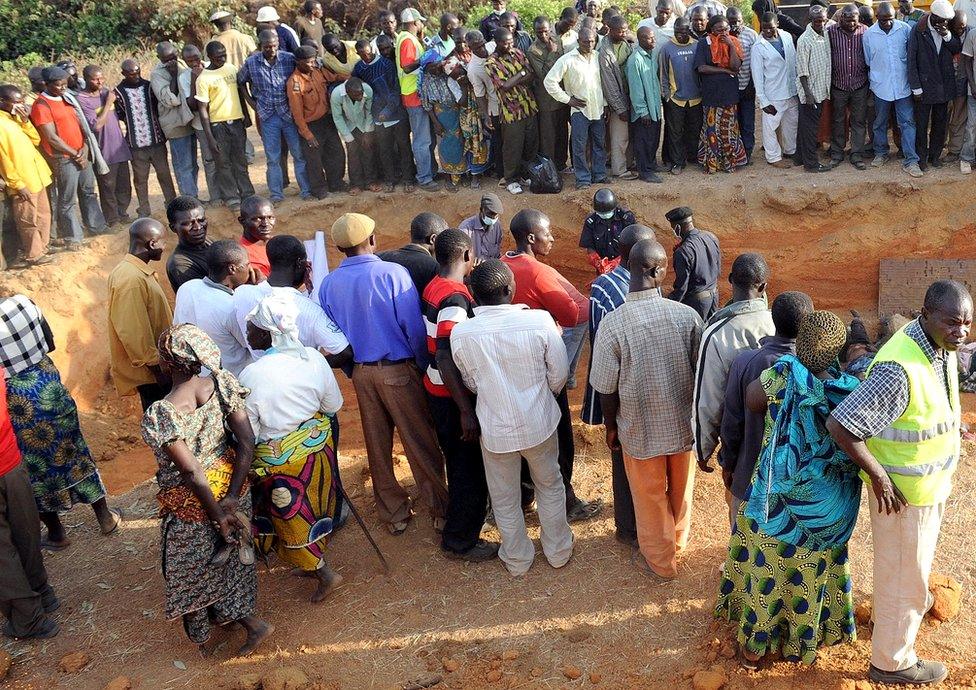

Mass burials - like this in Dogo Nahaw - have been a common thing during the conflict

In Barkin Ladi, 268km (167 miles) east of the capital Abuja, the period of more than five years in which thousands of people were killed in ethnic clashes is simply labelled "the crisis". The death rate across central and southern Nigeria averaged more than 2,000 a year between 2011 and 2016, according to campaign group Crisis International, external.

"The Fulani man destroyed the Berom man's farm, and the Berom man killed the Fulani man's cattle and the children rearing the cattle," says Farouk Abubaker, a tall, well-built Fulani man in a dusty beige tunic.

"We saw them as very wicked people. We saw them as barbarians because they killed little children and women, even pregnant women.

"A lot of horrible things happened - but all that is now history."

Because two years ago, it stopped.

Tin deposits were discovered nearby, just as global prices - driven by demand from electronic components manufacturers - were rising.

Now Mr Abubaker and Mr Botson work together on the same mining shaft, digging for the metal along the same narrow gorge that Fulani herders and their cattle pass through every day.

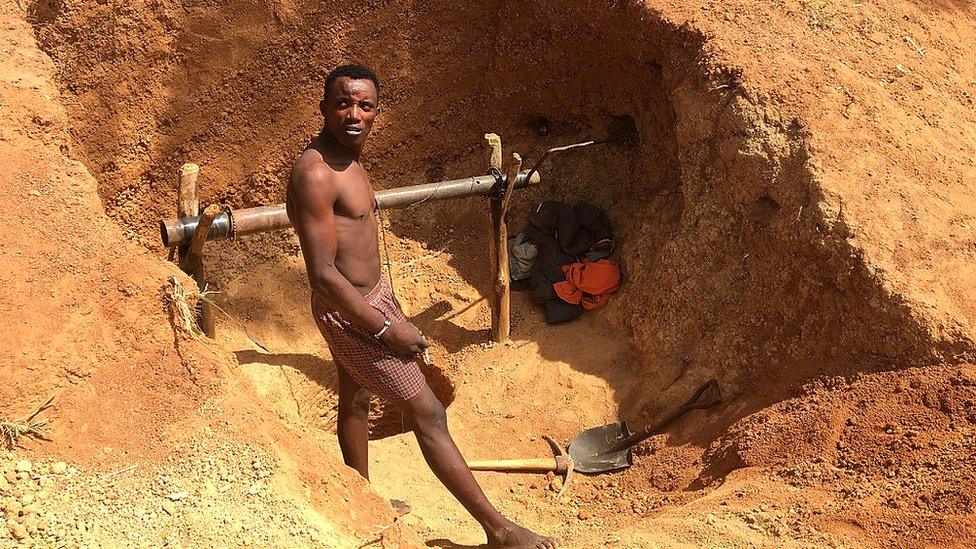

Dangerous work: Many people have died in shaft collapses

It's a hole in the ground as much as 40ft (12m) deep and just wide enough for one man to crawl into.

Using a bucket, shovels and a pulley system made from tree-trunks and a cable, these men plunge into the earth pulling out balefuls of dirt. It's dangerous work - many have died when mine shafts have collapsed - and they have to trust each other.

"I'm really surprised," Mr Botson says. "I didn't believe that we could live together like this; work together, talk together and do something like this together."

A pulley system is made from tree-trunks and a cable

Workers then pan for precious tin

From dawn, the mine buzzes with the sound of hundreds of men, women and even children.

Some of them crouch over shallow streams, sloshing the ochre-coloured dirt around in buckets until a dark grey metal appears. Others sell head torches, tools and batteries, or clear plastic bags of water and freshly cooked food.

Everywhere on this mine Fulani and Berom are working together in small teams. But how?

When a new governor was elected in Plateau state in 2015, he promised to bring an end to the crisis.

When he hired Joseph Lengmang, 42, as head of the Plateau State Peace Building Agency, many doubted whether a man that young would have the authority to summon local elders to sit down together.

"This government inherited an almost anarchic environment," Mr Lengmang recalls.

"It took quite some time. When it started they were shouting at each other, it looked like there would be violence. But we got experienced mediators... in the end we had a peace accord".

The Plateau Peace Building Agency's work continues across the state

Plateau state has been balancing on the precipice of a delicate peace ever since, with the ethnic conflict becoming a national crisis. Clashes occur across the country's Middle Belt almost every week, and six people were recently killed in Barkin Ladi.

Many also blame local and national politicians for stoking the tension to rouse support as Nigeria enters an election year.

It comes against a backdrop of three years of high inflation. While food prices have risen, so has the cost of fertilizers and fuel. And while many farmers rely on second jobs to subsidise meagre yields, unemployment has rocketed since 2013.

Mr Lengmang believes operations like the one in Barkin Ladi have a part to play in keeping the peace.

"It's very, very important... a means of livelihood to many people", he says. "They've learnt also in the experience they've had... if there is chaos and instability and violence, everybody loses".

However, he adds that there can be tension even among those working together in the mines, if the proceeds of their labour are shared "fairly".

Thomas Johji was one of a small group of Berom men who discovered this particular tin deposit a few months ago. As it was in the middle of a Fulani grazing area, it was crucial to get their neighbours' co-operation. So they invited Fulani people to mine with them.

Mr Johji is in his 20s and doesn't remember how "the crisis" began.

"Now we can even sleep here in the bush with the Fulani; wake up together, play together," he says. "The Fulani have forgotten about what happened, and we are trying to forget too."

It may not be that easy for most people. A deep sense of mistrust persists between the ethnic groups.

One Berom woman working at an older tin deposit nearby says she feels uncomfortable around Fulani people. She finds it difficult to trust those she says killed many of her friends and relatives.

"Even now we are afraid - but it is up to God," she says, adding that she is here out of pure necessity. "If you stay home, how will you eat?"

Mr Lengmang accepts Plateau state's uneasy peace is not yet sustainable.

"There are legitimate grievances that have not been addressed and a deep-seated sense of mistrust between ethnic groups," he says. "The mining process has to be more inclusive."

When tin deposits become scarce, fighting is bound to erupt over resources.

Mr Lengmang says miners have a role to play in peace-building. His agency is exploring whether they could lead training in conflict resolution, or encourage parties to sign peace accords before they start work on a deposit.

But Mr Abubaker believes the industry is already doing something to foster peace.

"Mining promotes unity and understanding among the different tribes," he says, "just as football does."

"It makes us happy. I pray - and hope - that we are able to sustain it."

Crossing Divides

Crossing Divides: a week of stories about people creating connections in a polarised world.

How to survive a difficult conversation

- Published11 January 2018

- Published5 May 2016