DR Congo crisis: Why a trainee nun was shot dead at church

- Published

Thérèse Kapangala, who was training to become a nun, was killed at a protest in January

The BBC's Africa editor Fergal Keane reports on how the Catholic Church has become the main opposition in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

By the time her brother arrived on the scene Thérèse Kapangala was already dead.

She lay in a pool of blood just inside the main door of the Church of St Francis de Sales, about 15 minutes from central Kinshasa.

Thérèse was a novice nun who grew up in a devoutly Catholic family in the narrow streets of Kintambo, an old Kinshasa neighbourhood where the colonial explorer Henry Morton Stanley established his first settlement in 1881.

She lived a short walk from the church.

'Revolt of the reasonable'

On Sunday 21 January she joined protesters who had gathered at St Francis calling for free and fair elections.

Mobile phone footage caught the moment when people fled the church compound in panic

Her brother Jean-Claude remembers hearing shooting and the firing of tear gas canisters.

"I said to her: 'Look there's a lot of tear gas, please take this margarine butter' because it is something we use to lessen the effects of the gas on our skin.

"But she already had some and threw away what I gave her. That day she was happy. She was joyful."

Mobile phone footage from the protests shows people fleeing in panic as tear gas and live ammunition were fired by security forces who surrounded the compound.

Thérèse was dead within minutes of being struck by a single round.

A small shrine had been erected to the memory of Thérèse Kapangala

"Even now I can't believe it," recalls her mother Mado Longo. "I think I am dreaming that she has only gone to rest. She was my child but also my friend."

We were sitting in the family's tiny sitting room. A small shrine had been erected to the memory of Thérèse - there was a memorial candle, some Rosary beads, a statuette of the Blessed Virgin, and a photograph of a serene-looking young woman in her 24th year.

"I can't stand the pain I feel," says Mado Longo Kapangala about losing her daughter

The Kapangalas are not natural rebels. Nor are they partisans of any political party.

In a country where politics has long been contaminated by corruption and division, where human rights abuses are endemic, they represent the revolt of the reasonable.

Thérèse belonged to a broad-based human rights movement that has succeeded in transcending ethnic divisions and challenging the deep-rooted culture of impunity.

'The church will never shut up'

This is not by any means exclusively rooted in the Catholic Church but in recent years clergy and lay people have been at the forefront of attempts to push for democratic change.

It began with church-mediated efforts in 2016 to achieve a peaceful transition from the rule of President Joseph Kabila, whose mandate expired in December that year.

When they failed, it morphed into a mass protest movement.

Security forces killed at least seven people at this anti-Kabila protest in December 2017 which was backed by church activists

President Kabila has so far failed to step down, overstaying the maximum two terms allowed by the constitution.

In a country where roughly half of the population is Catholic, the state tends to pay attention when the church intervenes in politics.

The leader of the Catholic Church in DR Congo, Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo, declared at the beginning of the year that it was "time for truth to win out over systemic lying, for the mediocre to clear out and for peace and justice to reign in DR Congo".

Read more about the many crises in DR Congo:

Ituri: 'My daughter was slashed with a machete'

But when priests led public protests the government cracked down with shootings, beatings and arrests.

After the bloodshed, Catholic lay groups called off the protests, saying they would wait to see if President Kabila was sincere about holding elections.

Apparently unconvinced, they announced on 1 May that the truce was over and promised a fresh wave of demonstrations.

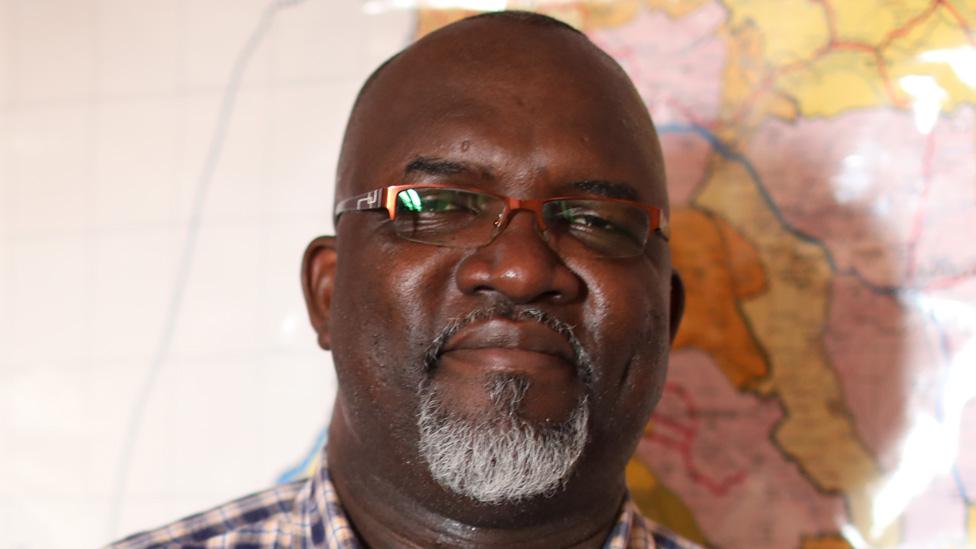

Father Joseph Musubao was at the church when Thérèse Kapangala was killed

"The church will never shut up. No force can make it shiver," says Father Joseph Musubao, a relative of Thérèse Kapangala who was saying mass at the church of St Francis on the day she was shot.

"The government's behaviour, their way of doing things, their mode of governing is indescribable… it is bloody and without regrets."

The state recently allowed a public meeting by the leading opposition party and has promised presidential elections by the end of the year.

But there is continuing suspicion that elections will be delayed again or rigged.

Morally bankrupt?

When I met the Information Minister Lambert Mende, I put it to him that the church was taking a moral leadership role because the government was seen as morally bankrupt.

He replied by denouncing the activities of the Catholic groups.

"I don't know if it is because the government is bankrupt that the bishops are taking a moral role. But they don't have the role… If you want to play a political role please go for elections and tell people to give you a mandate."

The Catholic Church is powerful in DR Congo where nearly half population are believers

It is possible that elections will take place by the end of the year. But will they be free and fair? Is Mr Kabila really ready to hand over power?

The promised return to the streets of Catholic-led protest groups would be a significant test of the government's true intentions.

Another violent crackdown like that which led to the death of Thérèse Kapangala would not bode well for the hopes of peaceful change in Africa's second-largest country.

DR Congo's political crisis in numbers

13 million people in need of humanitarian assistance

More than 4 million displaced

More than 7 million face severe food insecurity

Two million children at risk of starvation- 12% of cases worldwide

(Source: UN)

- Published27 March 2018

- Published14 December 2017

- Published17 February 2018

- Published28 January 2018

- Published12 December 2017

- Published6 December 2017

- Published9 October 2013

- Published31 January