How Mozambique’s smuggling barons nurtured jihadists

- Published

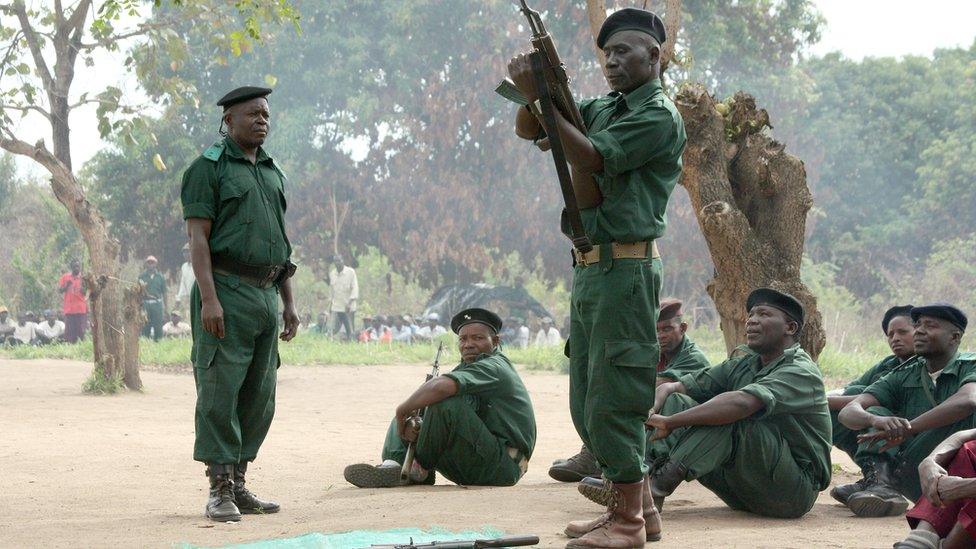

The army has increased patrols in northern Mozambique since the attacks began last year

Attacks by young Islamist militants in northern Mozambique are fuelled by a mix of poverty and corruption, writes Joseph Hanlon.

In the most recent attack, 10 people were decapitated with machetes in Palma district in the country's northerly Cabo Delgado province.

More than 300 people have been detained by the police and army since the first attack in the port town Mocimboa da Praia on October 2017.

Coastal northern Mozambique has a long history of trade and movement of people with the rest of East Africa, and people in this area are traditionally Muslim.

The offshore discovery of one of the largest natural gas fields in Africa in 2010 triggered dreams of wealth, but so far there has been little impact locally.

Gas will not be produced in the region until 2022 and there will be no serious government revenue until 2028 or later.

There is currently offshore exploration work being done and onshore construction of infrastructure. But as is common with mega-projects of this kind, few local opportunities have materialised.

Youth unemployment therefore remains very high, as in the rest of Mozambique.

Growing cells

In 2015, poorly educated and marginalised young men, many of them itinerant street traders in Mocimboa da Praia, formed small groups and began to organise around a rudimentary form of Islamic fundamentalism.

In the wake of the attacks, some mosques have been destroyed in Cabo Delgado by the authorities

They blamed both the mosques and the Mozambican state for their plight, and decided to challenge both.

Groups marched into local mosques wearing shoes and carrying knives as an intentional sign of disrespect of what they saw as "degenerate Islam". Local people called them "al-Shabab", simply local Arabic for youth, or just "the Shababs".

The small cells realised the need to look outside both for weapons and religious training, and found surprising allies.

Smuggling networks

Mozambique has become increasingly corrupt in recent years and its coastal north has become a major centre for ivory, timber, heroin and ruby smuggling - with the involvement of police and other government officials.

Mozambique is home to the world's biggest ruby and pink sapphire deposits

Local smuggling barons incorporated the militant young men into their networks and paid them well.

The nearby border with Tanzania is not controlled and there has always been a movement of people. This has increased with more people smuggling - mainly from Kenya, Somalia and the Great Lakes through Mozambique to South Africa.

There were already young Tanzanian men in the Mocimboa da Praia street trading community who became part of the groups.

After the 2012 killing in Kenya of Muslim cleric Aboud Rogo Mohammed (accused of supporting al-Shabab in Somalia), his followers came under pressure and moved south.

They built a presence in Kibiti, Tanzania, and crossed the Ruvuma River into Cabo Delgado by 2015.

Mozambique's jihadists are believed to have been influenced by the followers of the late radical Kenyan cleric Aboud Rogo Mohammed

Using incomes made from smuggling, religious networks, and people-traffickers, the extremist cells paid to send young men to Tanzania, Kenya and Somalia for military and Islamic training.

The income also helped bring radical clerics to Mozambique.

Within Mozambique, they hired a sacked policeman and two dismissed border guards to provide military training.

Guerrilla tactics

A study of these groups based on a month of fieldwork by Mozambican Islamic cleric Sheik Saide Habibe and researchers Salvador Forquilha and João Pereira was reported in Maputo on 22 May, external.

The structure remains one of small cells, of 10 to 30 people, who are linked but only loosely, the study found.

Most of the attacks appear to have been done by a single group.

This loose guerrilla format makes it difficult for the army and police to find these small groups.

There is now a large presence of army and riot police in three districts of Cabo Delgado. They have been accused of heavy handed tactics and of killing local people.

Two helicopters and a navy ship shelled the village of Mitumbate near Mocimboa da Praia on 23 and 24 December 2017 with at least 50 casualties.

Find out more:

Villagers were accused of supporting the young Islamist militants.

The shelling was in response to an ambush of a riot police convoy on 17 December, which was going from Mocimboa da Praia to Mitumbate, in which the riot police's national director of reconnaissance was killed.

The growing role of young Islamic fundamentalists and incidents like mosque invasions had been reported to local and provincial police and officials since 2015.

But the response has been to turn a blind eye - partly not to rock the boat and jeopardise their own jobs by giving bad news to their superiors, and partly because the young militants have the support of the smuggling barons.

Jihadists' tactics have been compared to those of ex-rebel group Renamo during a 16-year civil war

Some commentators have pointed to the attacks' similarity to common guerrilla tactics, and also to the actions of the Renamo guerrilla movement in Mozambique when it first started in the late 1970s.

There is no overt political agenda and the first step is to establish a presence through fear, including atrocities such as the recent beheadings.

Final goal

At the same time, they need to recruit new members and gain local support, and this is apparently being done through family links.

But the final goal is to encourage overreaction by the government, which they hope will turn communities against the government and toward them.

All of that appears to be happening in coastal Cabo Delgado.

The scenic environs of Mocimboa da Praia have been home to a number of attacks

Meanwhile, Mozambique will have municipal elections on 10 October and national elections in 2019.

Frelimo, which has governed since independence, is facing a growing backlash, in part because of the lack of rural development and the failure to create jobs - exactly what is at the heart of the Islamist youth militancy.

Although Cabo Delgado has always voted overwhelmingly for Frelimo, the opposition - both Renamo and Mozambique Democratic Movement (MDM) - has also done well in these coastal areas.

Only time will tell whether the impoverished region's lack of development, jobs, growing corruption and heavy-handed response to extremism will help the opposition in the polls.

It could also be the toxic recipe needed to help grow these nascent extremist groups.

Joseph Hanlon is a visiting senior fellow at the London School of Economics and editor of Mozambique Political Process Bulletin

- Published25 October 2024

- Published10 February 2017