How WhatsApp has helped heroin become Mozambique’s second biggest export

- Published

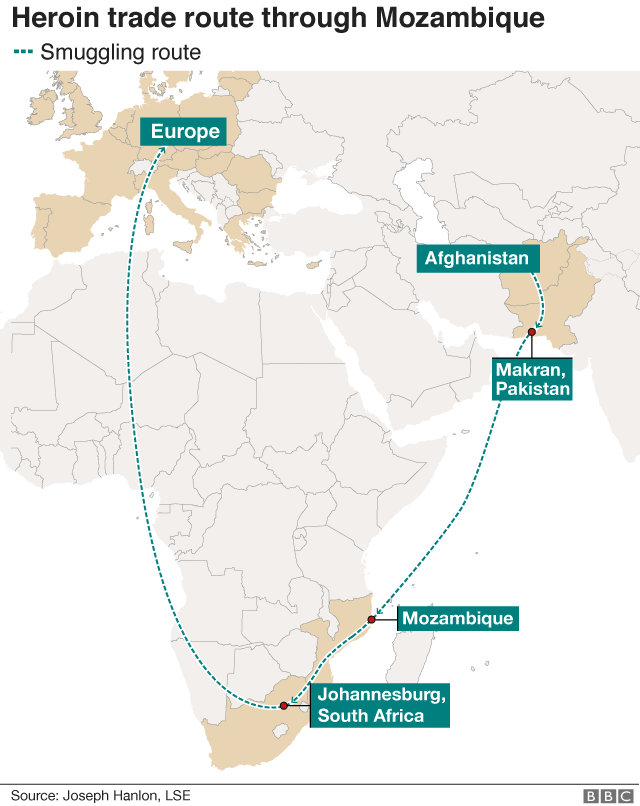

Some of the drugs that end up in Europe come via Mozambique

As many as 40 tonnes of heroin could be passing through Mozambique every year, making it the country's second biggest export, in a trade that is boosted by the use of mobile phone apps, writes Mozambique analyst Joseph Hanlon.

Mozambique is now an important stop for heroin traders who are using circuitous routes for their product to reach Europe from Afghanistan, as tighter enforcement has closed off the more direct paths.

The heroin goes from Afghanistan to Pakistan's south-west coast, and from there it is taken by motorized 20m wooden dhows to close to northern Mozambique's coast.

The dhows anchor offshore and smaller boats take the heroin from the dhow to the beach, where it is collected and moved to warehouses. It is then packed onto small trucks and is driven 3,000 km (1,850 miles) by road to Johannesburg, and from there others ship it to Europe.

Each dhow carries a tonne of heroin, and one arrives every week except during in the monsoon season, which makes about 40 arrivals a year.

Heroin also comes in by container into the country's Nacala and Beira ports where it is hidden among other goods, such as washing machines.

Overall, this means that at least 40 tonnes of heroin pass through through the country each year, according to experts. I estimate that the drug is worth $20m (£15m) per tonne at this point in the trade, making it the country's second most valuable export, after coal.

Mozambique's biggest exports:

Coal - $687m (2016)

Heroin - $600-800m (est)

Electricity - $378m (2016)

Aluminium - $378m (2016)

Gas and oil - $307m (2016)

Source: Mozambique government; Joseph Hanlon

Out of the export's total value, about $100m is estimated to stay in Mozambique as profits, bribes, and payments to members of the governing Frelimo party.

Since 2000 the heroin trade has been carried out by established import businesses, which hide the drugs in legitimate consignments and use their own warehouses, staff and vehicles to facilitate their movement. At ports, workers are told not to scan containers of certain trading companies so the drugs are not discovered.

Political involvement

Senior Frelimo figures have an overview of the business, meaning that there has been no conflict between trading families and little heroin remains in Mozambique.

Police spokesman Inacio Dina said the authorities were investigating these findings. He said the police were doing their best to stop the drugs trade but admitted it was a huge challenge.

"We must understand that the country's geographical location, with a lengthy coastline, and long land borders, opens various scenarios."

On its part, the international community has largely chosen to ignore the heroin transit trade, because it wanted concessions and reforms in others areas, such as an ever larger role for the private sector.

But a second, less structured, arm of the drugs trade has also emerged, borrowing ideas from the "gig" economy, where freelance workers are contacted through mobile phone apps to see if they are available.

Dhows are used to ship heroin from the Pakistani coast to near Mozambique

This has been facilitated by the improved mobile phone coverage in northern Mozambique, the growth of WhatsApp and its encrypted message system, and increasing corruption in Mozambique.

In the case of Mozambique's heroin trade, a driver or boat owner will receive a WhatsApp message telling them where to pick up and deliver a package of heroin, and how to be paid.

Secret network

No-one knows the identity of the person who sent the message or their location. For those people coordinating the trade, ordering the movement of 20kg (44lb) of heroin is as easy as ordering an Uber taxi, and totally secret.

Two decades ago, corrupt police officers would have accompanied drivers with shipments of heroin on the north-to-south-Mozambique leg of the journey, to ensure they were not stopped at the numerous police checkpoints.

You may also like:

Then as mobile telephone coverage improved, drivers were given a number to call if they were stopped. But the extent of the corruption has changed that and drivers are now given a pile of money to pay bribes at checkpoints. Whatever is left of this money when they arrive in Johannesburg is their pay for the trip.

No heroin is seized in Mozambique, but there are confiscations near the border in South Africa, because authorities there are worried about rising use of heroin in Cape Town and other big cities.

Heroin, grown in Afghanistan, makes its way to Europe through Mozambique

Those seizures show that heroin is often branded and sealed in 1kg packages in Afghanistan, apparently to prevent it from being adulterated along the long travel route. Among the brand names that have come to light are 555, Tokapi and Africa Demand.

In this new world of encrypted messaging apps, a buyer in Europe can place an order for 100kg of 555 with a distributor who may be anywhere.

The distributor puts together enough orders to make up one tonne on a dhow, and arranges collection in Mozambique and delivery to a warehouse, contacting local coordinators using WhatsApp or a similar app. In the warehouse, the tonne is broken up again into the different orders which are sent to Johannesburg.

Indeed, Mozambique's heroin trade looks like the trade in any other commodity - just another product moving through Mozambique and coordinated by multinational organisations.

Joseph Hanlon is a visiting senior fellow at the London School of Economics and editor of Mozambique Political Process Bulletin. This is a shorter version of his full report which can be read here, external.

- Published25 October 2024

- Published2 June 2018

- Published25 May 2017

- Published10 February 2017

- Published23 October 2016

- Published10 February 2017