Cape Town anger over slave quarter gentrification

- Published

The character of a historic quarter in South Africa's city of Cape Town is under threat by gentrification, long-time residents tell the BBC's Mohammed Allie.

The historic area of Bo-Kaap with its picture postcard pastel-coloured houses, rich cultural heritage and beautiful location overlooking Cape Town's city centre has always been a favourite stop for tourists.

But over the past few months, the area, which adorns many of the city's tourism brochures, has been the centre of attention following continued public protests against gentrification, characterised by a growing number of high-rise buildings and steeply rising property rates that many long-standing residents can no longer afford.

Residents stage a mass breaking of the Ramadan fast to protest against gentrification

Protests have included a mass breaking of the Ramadan fast on one of the area's main streets.

Spearheaded by Bo-Kaap Rise! - a movement initiated by the area's youth - the protests have brought into sharp focus the residents' grievances together with the need to maintain the historic area's rich cultural heritage.

Dating back to the 1760s, Bo-Kaap was originally known as the Malay Quarter because it was first inhabited by slaves from Asia, as well as some from the rest of Africa, Historically, it is a Muslim area and home to South Africa's oldest mosque, built in 1794.

The houses, a mix of Cape Dutch and Georgian architecture, run alongside steep cobbled roads.

The choice of bright pastel colours is believed to stem from an expression of freedom when the owners were allowed to buy the properties, a move that lifted the previous restriction imposed by the colonial authorities that demanded the houses be painted white.

Bo-Kaap sits between Table Mountain and the centre of the city

Many of the families in the neighbourhood have been living there for generations, but despite its prime location, which offers sweeping views of Table Mountain above and the harbour area below, Bo-Kaap has never been a rich area.

But things began to change after the apartheid-era Group Areas Act, which restricted areas to a particular racial group, was abolished in 1991. The Bo-Kaap property market then opened up to rich foreigners, as well as to well-heeled South Africans from other communities.

'Turn down prayer call volume'

Over the past two decades some of the area's residents, unable to resist the tempting offers, have sold their properties and moved out.

Bo-Kaap is home to 10 mosques and has a largely Muslim population

Bo-Kaap Rise! spokesperson Shakirah Dramat says while she understands that people have the right to move, she believes they also have a duty to preserve their heritage.

"We need to educate people about the heritage of the area. This is why it's important for us to keep the little bit of Bo-Kaap we have left because the reality is that over the last few decades our area has shrunk," says Ms Dramat.

"Bo-Kaap is one of the most important parts of the heritage of South Africa. The slaves in the 1700s and 1800s are the people who built the city.

"There's no problem with outsiders moving into our area as long as they respect the culture, this is obviously a largely Muslim area.

"There is a problem when people start calling for the volume of the call to prayer from the mosques to be turned down, when they open restaurants that serve alcohol and pork - that's blatantly disrespectful," she adds.

The area is popular with tourists and features in guide books and brochures

Osman Shabodien, chairman of the Bo-Kaap Ratepayers Association, is also quick to dismiss suggestions that protests are trying to maintain a sense of cultural exclusivity.

"For decades Bo-Kaap has been multi-cultural and we haven't had any problems," he says.

"Many of us attended the St Paul's Parish school, the St Monica's Maternity Hospital was donated by the church - there's been Muslim, Christian and Hindus staying in the area for all the years.

"Gentrification doesn't have colour, it has money and attitude that doesn't tolerate other people's cultures."

More on Cape Town:

Mr Shabodien is also concerned that the foreigners who do not live in their recently bought homes throughout the year are damaging the fabric of what has always been a closely knit community.

"We're opposed to absentee landlordism because you can't build a community if nobody is home. Many of the new owners are only here during our summer and then leave the homes empty while they go back to Europe for their summer."

Bo-Kaap has a reputation of being a friendly and welcoming community

Some of the newer residents also have concerns about the changes.

"There's centuries of building and cultural heritage in the Bo-Kaap that's being destroyed by inconsiderate developers who get the green light from the city despite objections from us the residents," says John Ziniades, who moved into the area nine years ago.

"Sometimes this issue has been turned into one that portrays the community as seeking to maintain Muslim cultural exclusivity which is completely wrong.

"Ever since I moved into the area, as someone who had no links with the area, I have been welcomed into the Bo-Kaap community with open arms."

A rise in property rates has made it more difficult for some people to stay in the area

Besides the attractive offers made by prospective buyers, the increased property rates - a local tax based on the value of the property - have also made living in the area unaffordable to many.

'My neighbours don't greet me'

Faheema Mathews who has lived in Bo-Kaap for 35 years is a case in point.

"My rates have increased four-fold from 400 rand ($30, £22) per month to 2,500 rand ($186, £140) per month - it's not affordable. It's just getting totally out of hand.

"I'm determined to stay, but maybe I'll have to rent because it's no longer affordable to live here, but I wouldn't like to sell.

"My neighbours are now German and French people, they don't greet, there's no communication.

"I miss my old neighbours who have left. That closeness we had in the past is gone."

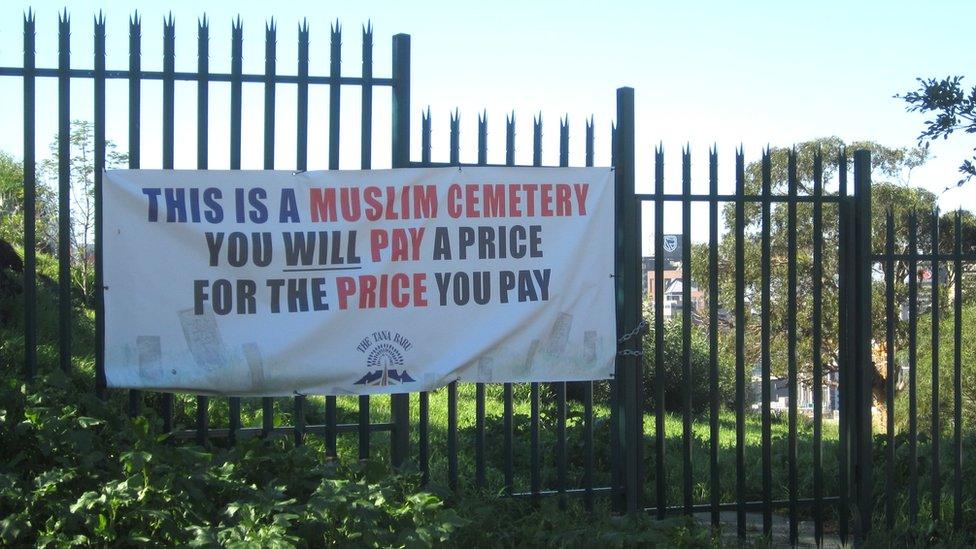

Greater community awareness engendered by the recent protests played a role in halting the proposed auction of 20% of the historic Tana Baru graveyard. This was where the country's first Muslims were buried in the 17th Century.

Activists were opposed to selling off part of a cemetery for development

"We can't sell this land. Our forefathers are buried here. The pioneers of Islam are buried here," said Cassiem Abdullah, who disagreed with his own family members to their proposed auction.

Mr Shabodien is preparing for a long series of legal battles against developers and the authorities in their efforts to retain the unique character of their area.

"The protests have woken community - if we don't do something about the gentrification now we will lose our heritage," the Bo-Kaap Ratepayers Association chairman says.

"We need heritage protection to safeguard us against the greedy developers and the short-sightedness of government."

Pictures: Getty Images

- Published11 October 2016

- Published1 February 2012