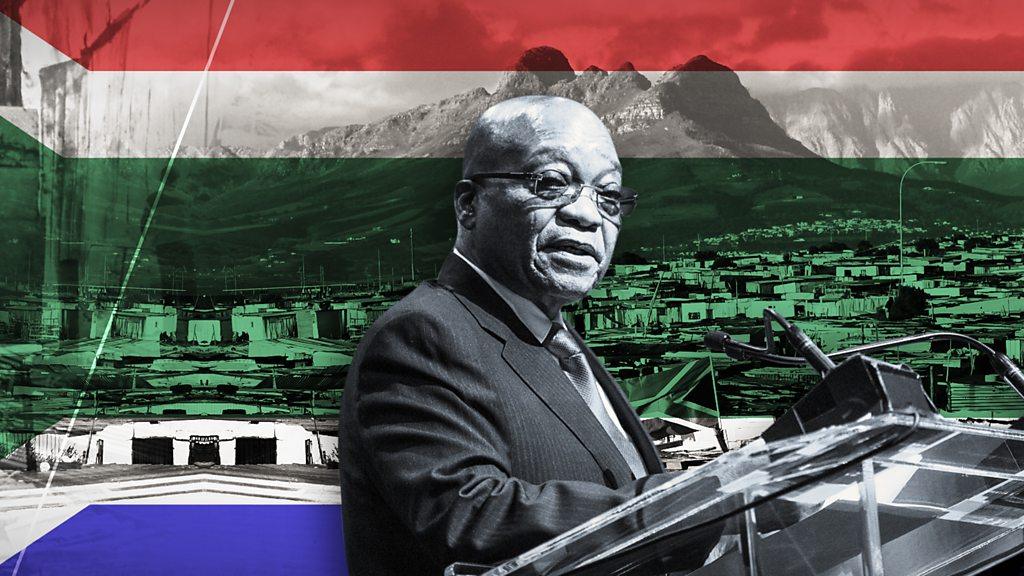

Will South Africa's Jacob Zuma come back to haunt Cyril Ramaphosa?

- Published

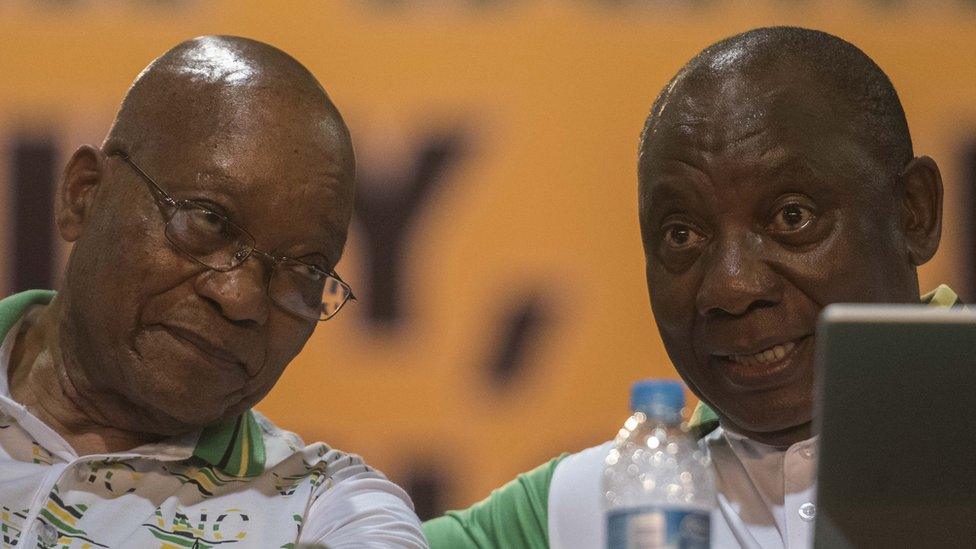

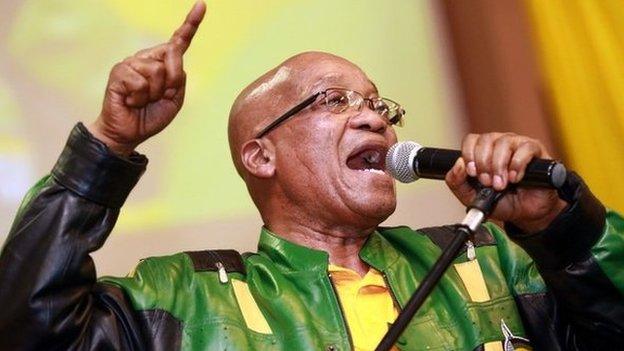

Is Jacob Zuma (L) scheming to frustrate his successor Cyril Ramaphosa?

Jacob Zuma has not had an easy retirement.

In the five months since he stood, glumly, before the cameras to concede that he had lost the battle to cling onto South Africa's presidency, he has been forced to endure multiple humiliations.

He has been charged with corruption, has seen his son, Duduzane, taken to court in leg irons on separate corruption charges; and has watched a seemingly relieved public rally around his successor, Cyril Ramaphosa, in what has been dubbed here as a mood of "Ramaphoria."

And yet…

In recent weeks, tantalising signs have appeared indicating that Mr Zuma - an acknowledged political heavyweight with once-revered powers of survival - may not be an entirely spent force.

Indeed, there is now growing concern in some quarters in South Africa that the ghost of the Zuma era - a bitter, vengeful, and disruptive spirit - may be plotting some sort of comeback.

"We're fairly certain that the infrastructure of Mr Zuma is engaged in a fight-back strategy… to paralyse Mr Ramaphosa, delay his reforms, delay improved economic circumstances, and exploit the ensuing populist fervour to destabilise this new administration," says Frans Cronje, a political analyst at the Institute for Race Relations in Johannesburg.

So how do you spot a ghost, or, perhaps, a poltergeist? Do such things even exist in politics?

To borrow - apologetically - from the world of spiritualism, maybe these tarot cards can help guide us.

The Hanged Man

I'm told this card refers to change, rebirth and improvement, rather than to South Africa's justice system, but the need for rebirth in the country's National Prosecuting Authority is a constant and urgent theme here, so please bear with me.

For years, powerful figures allegedly involved in the "state capture" - the looting and co-opting of state institutions by politicians and their business partners - have appeared to enjoy something close to immunity, courtesy of a national prosecuting chief who was routinely mocked as "Sean The Sheep" for his perceived loyalty to Mr Zuma.

Many South Africans were hoping that would change abruptly with a new president in charge. But although there have been some positive new developments - corruption charges reinstated against Mr Zuma himself, for instance - progress has been slow and many powerful figures implicated in corruption remain openly defiant and untouched.

The Emperor

Trouble is brewing, not for the first time, in the former president's home province of KwaZulu-Natal.

The Zulu monarch Goodwill Zwelithini recently appeared to threaten both violence and a move to secede from South Africa if the governing ANC made any move to strip him of control of thousands of hectares of traditional land.

The ANC had indeed been discussing such a move, but rather than pointing to the outdated and feudal nature of the king's control over those living on his land and the alleged corruption involved in the whole setup, President Ramaphosa rushed to the king's palace to assure him that his land was safe and, presumably, to ensure his continued support for the ANC.

A politically necessary move, perhaps. But is it any coincidence that Mr Zuma's old stronghold is the focus of so much tension and discontentment both within the ANC and beyond?

The Magician

Speaking of land ownership… The biggest political theme of the moment in South Africa is the idea of changing the constitution to allow for the expropriation of land without compensation.

The aim is to seize white-owned land and critics fear a repeat of the chaotic Zimbabwe land grabs of the early 2000s.

This issue is a poisoned chalice left behind by Mr Zuma for his successor.

But the real magician in this instance is Julius Malema, leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party - which secured only single-digit support in the last elections and yet has not only championed the land issue but is now routinely outmanoeuvring the ANC with its radical agenda and populist swagger.

Mr Ramaphosa, a naturally cautious figure, needs to find a way to regain the initiative from the EFF, steer the land reform issue away from potential Zimbabwe scenarios, and ensure an already shaky economy is not further damaged in the process.

But parliament's nationwide public hearings on the issue are playing into the EFF's populist hands and there is no indication yet that Mr Ramaphosa has found a way to take back control of the agenda.

The Wheel of Fortune

Many of Mr Ramaphosa's biggest headaches lie within the governing ANC.

He may have won control of the party last year, but he did so by the narrowest of margins, defeating a faction closely linked to Mr Zuma thanks only to some last-minute, opportunistic defections.

It is hardly a platform from which to overhaul the party, even if, as expected, Mr Ramaphosa manages to lift the ANC's share of the vote back over 60% at next year's national elections.

You might also be interested in:

On the surface, the ANC is busy trying to prove that it is a united force, but no-one is convinced. Factionalism is, as Mr Zuma himself once admitted, eating the party alive.

"Just five more years," is the chorus now being sung, quietly for now, by Mr Zuma's allies as they bide their time, undermine Team Ramaphosa at every opportunity, and wait for the wheel to turn so they can seize back power at the next ANC electoral conference.

The Hermit

Cyril Ramaphosa is something of an enigma.

He's a famous and formidable politician and negotiator, and an extremely wealthy businessman; but he's also a private man who lacks Mr Zuma's front-man swagger and seems to prefer the backroom work of building consensus and empowering institutions.

In the space of a few months Mr Ramaphosa has, arguably, begun putting South Africa's economy back on the road to recovery, or at least halting it at the cliff edge. But the task ahead remains daunting.

Mr Ramaphosa has inherited a bloated, dysfunctional civil service from his predecessor, along with dangerous levels of debt and corruption-riddled parastatal organisations - like the broken state electricity company Eskom - which continue to drain billions from the budget.

Youth unemployment is soaring. Millions of school children are being let down by a faltering education system. And the mainstream opposition is struggling, leaving space for more radical parties to seize the initiative.

Slaying the ghost

Is the patient Mr Ramaphosa the right man to exorcise the ghosts of the Zuma era, grab a faltering nation by the neck, and drag it back towards economic growth and political stability? Many here are starting, impatiently, to wonder.

Perhaps the larger question is whether such a mission is even possible - regardless of whether a hermit, or a fool, or any other tarot card is in charge.

South Africa is currently in the grip of centrifugal forces - above all, within a fractious ANC that is preoccupied with fighting over the spoils of a faltering economy rather than working out how to produce new wealth.

It could be argued that Jacob Zuma was a symptom of those forces rather than their creator and that Mr Ramaphosa now finds himself in much the same, leaky boat.

"It is the nature of the beast," says businessman and political commentator Moeletsi Mbeki, who bemoans a culture of grievance, and a preoccupation with reparations from the apartheid era, among those competing for power and resources in South Africa.

"There is war among the black elites and, when the cake is shrinking, that war is much more bitter than when the cake is growing."

- Published14 February 2018

- Published9 October 2017

- Published6 April 2018

- Published20 July 2017