How the Ethiopia-Eritrea peace process could reunite one family

- Published

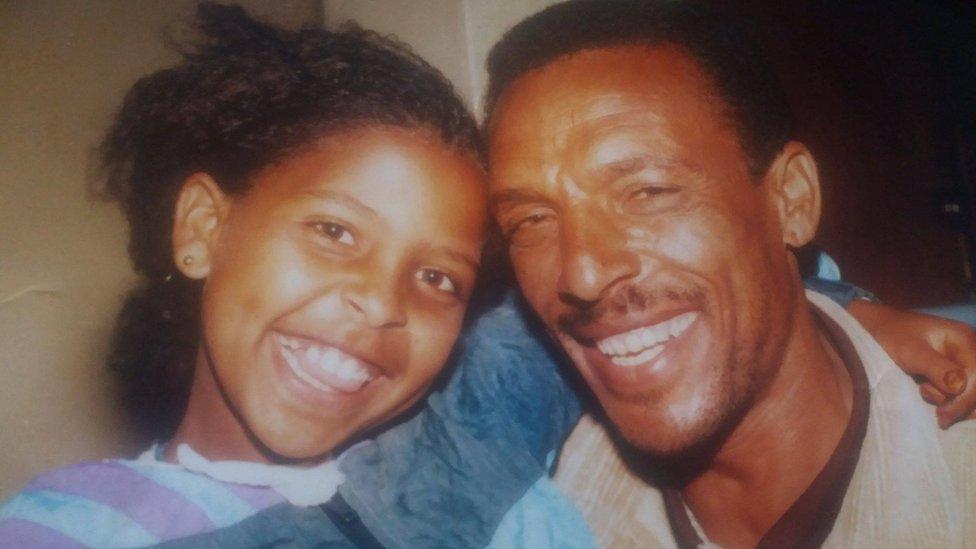

In happier times: Addisalem Hadigu's daughter is now an Eritrean soldier

Ethiopian journalist Addisalem Hadigu hopes to see his Eritrean wife and two daughters for the first time in 16 years.

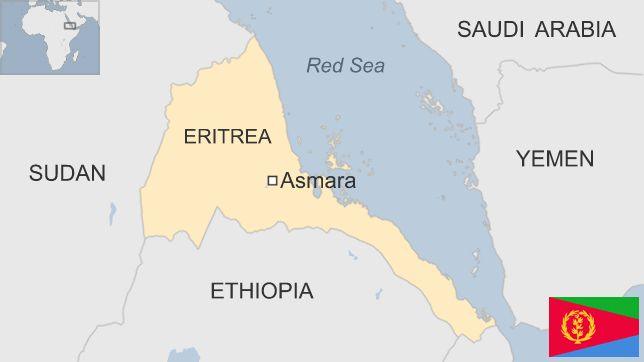

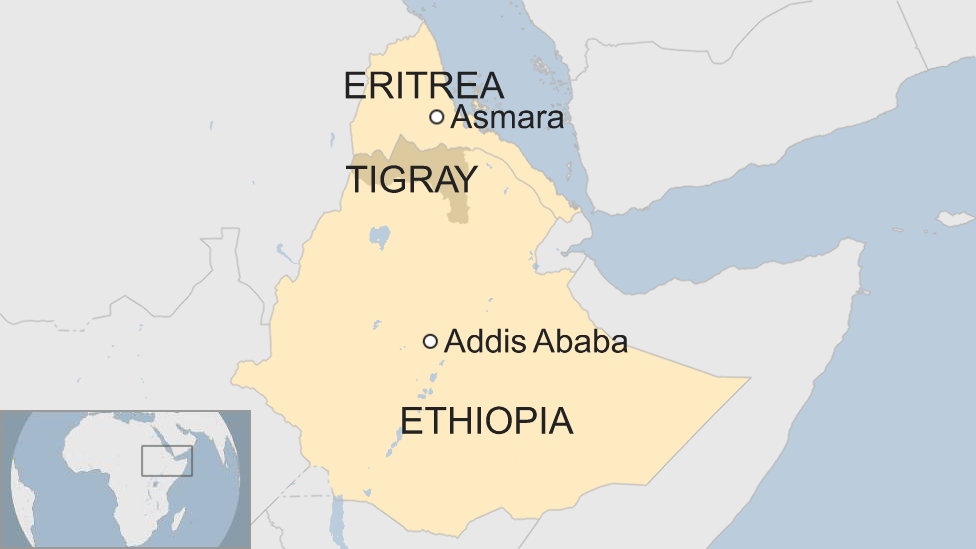

It comes after the leaders of the two nations signed a declaration, ending the "state of war" which has existed since their armies fought for territory between 1999 and 2000.

Road and air links between the two neighbours are expected to reopen in the next few days, while phone lines have already been restored.

Addisalem told BBC Tigrinya's Hana Zeratsyon how the conflict destroyed his marriage and split up his family:

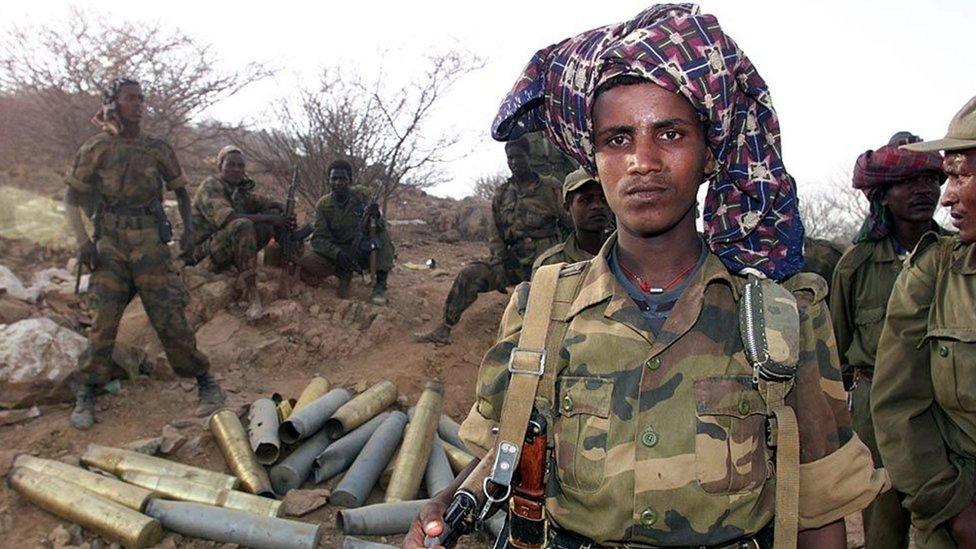

I lost two of my younger brothers in the war that claimed the lives of tens of thousands of people.

It made families, including mine, see each other as enemies.

I married an Eritrean, Mitslal Abrha Dirar, in 1980, when we were both 20.

In 2002, two years after the end of the border war, my wife left me - taking our two daughters with her to Eritrea. I have not seen any of them since.

As an Eritrean citizen, my wife had lost her right to work as a teacher in Ethiopia. I was worried that she would be sent back to Eritrea.

So, I helped her get an official document from Ethiopia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stating that she was married to an Ethiopian and could therefore remain in the country.

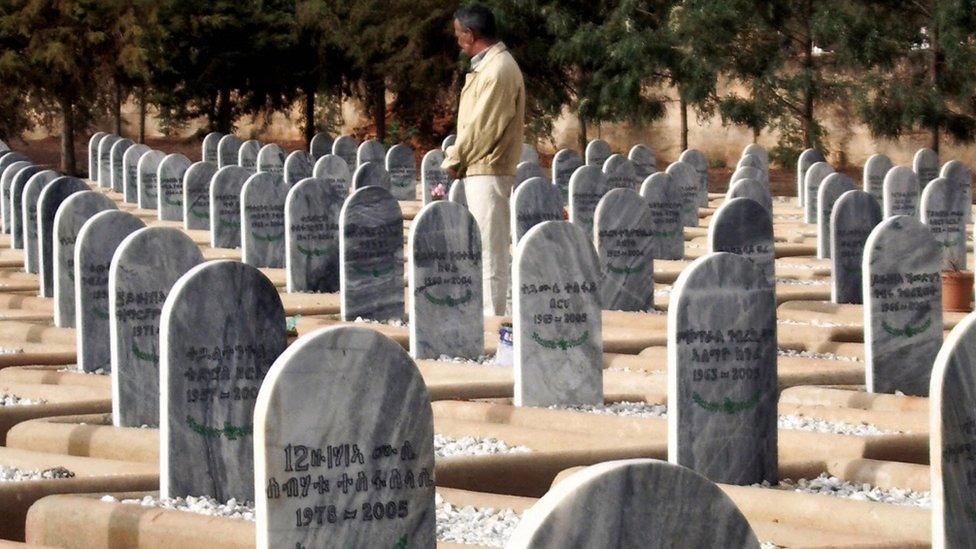

Tens of thousands died in the bitter border war

My wife had also voted in a referendum in 1993, in which Eritreans formally voted for independence, after a struggle which had lasted for 30 years.

She hesitated in participating, but I told her to do it.

I said she could tell our children the history - that their father is from Ethiopia's Tigray region and their mother from Eritrea.

I took her to vote. My wife, along with 99% of Eritreans, voted to secede from Ethiopia.

Perhaps this is why she lost her job - and felt she had to leave.

'I felt like I had died'

It was on a Wednesday when my wife told me that she was going to visit her uncle, who lived elsewhere in Ethiopia.

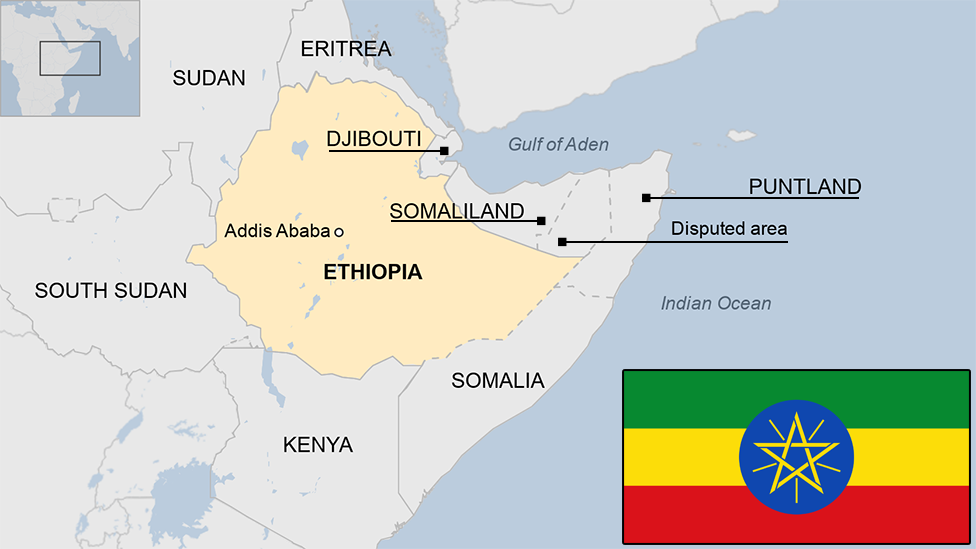

The road from Ethiopia to Eritrea is expected to reopen in the coming days

I waited for her to come back with our children, but they never returned.

I learned that she had crossed into Eritrea, as a refugee and was living in a camp.

The border was closed to Ethiopians, so I could not go after her. I felt like I had died.

'No reply to letters'

My family accused me of doing something bad to my wife, saying this is why she had decided to go back home. But I know this isn't true.

We were very close and respected each other. We knew only laughter and happiness in our family.

She did not have any family in Eritrea when she left.

My wife left a letter for me with our neighbours.

"This feels even worse than losing someone through death. I have left for Eritrea with my children," she wrote.

"I leave the boy with you. If I get any chance I will write to you, if not take care of yourself."

My neighbours sat for a week with me while I was in mourning.

After this, I could not tell you in words the life I lived. It might be easier to draw it in pictures.

I was insane. I was like a dead man walking. My life was without meaning, without taste.

I wished I could die. Every day I would go to work and drink. This was my life.

The war cemetery in Eritrea is a reminder of decades of conflict with Ethiopia

Until Ethiopia's new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took steps in recent months to normalise relations with Eritrea, it was impossible to think that our countries would ever make peace.

I used to wish my family had moved to any other country - because it would have been easier to visit them there than to cross the border into Eritrea.

I used to send letters to my wife through the Red Cross, which helped families separated by the conflict to trace each other.

But I stopped writing to her because I never received any reply. I still want to meet her to find out why she left me.

'Wise beyond her years'

I wrote to my daughters, Asmera Addisalem and Danait Addisalem, three times, and received a reply once.

Since the advent of social media, I've had contact with them via Facebook, but not consistently.

My youngest daughter, Danait, used to always ask how I was, and say: "We cannot talk in voice, but we miss you."

I have not spoken to them for some time now.

Many Ethiopians and Eritreans in the diaspora have come out in support of the peace process

I know that my youngest daughter graduated from technical college and joined Sawa Military Training Camp.

Now she is a soldier - which means I can't talk to her any more.

Those doing national service in Eritrea cannot carry mobile phones.

I imagine her life to be tough. Though I have incredible love for all my children, I have an especially deep love for my youngest daughter.

She is intelligent and wise beyond her years. She does not tolerate lies and theft.

More on the Ethiopia-Eritrea reconciliation:

Making peace with 'Africa's North Korea'

The man who is changing Ethiopia

The story behind Africa's unfinished war

You can get the latest BBC news in Afaan Oromo, Amharic and Tigrinya.

I badly want to see my daughters again and pour out what I have had in my heart all these years.

I've already started to search for them, and hope to find a residential address soon.

Now I am 58 years old. I did not expect to be still alive, but I live only to see my daughters and wife again.

'Beginning a new life'

Even now, in my dreams, I see my children. And when on Sunday I saw Eritrean mothers welcoming Mr Abiy in Eritrea's capital Asmara, I saw my daughters and my wife in the faces of those mothers and children.

Eritreans came out in large numbers to welcome Ethiopia's prime minister

Now I want to go to Asmara, meet my old friends, and begin a new life.

I want to see my daughters dressed well. I need to touch their hair, wash their hands, smell their smell and see them looking after me for I am an old man.

If this day ever comes, I will say I am born again.

And of course, I will take my son with me. He, too, wants to see his sisters after all these years of separation.

- Published10 July 2018

- Published11 October 2021

- Published2 January 2024

- Published18 April 2023