Reality Check: Why some African countries don't want charity clothes

- Published

Rwanda is planning to ban the import of second-hand clothes

Claim: Donating second-hand clothes has had a negative effect on textile industries in African countries.

The Rwandan President, Paul Kagame, has said: "We are put in a situation where we have to choose - you choose to be a recipient of used clothes... or choose to grow our textile industries."

Rwanda is planning to ban the import of second-hand clothes by 2019 and has already put up tariffs.

Verdict: Imports of cheap second-hand clothes from the West have had an impact on local clothes manufacturers - but so have changes in world trade policies and the rise of Asian garment producers.

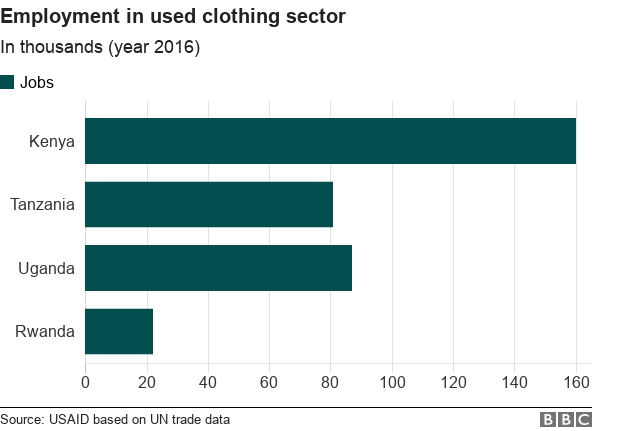

The hand-me-down trade also employs thousands of people in some countries.

African countries once had large textile industries - and some critics blame the flood of cheap second-hand clothes from abroad for the continent's shrunken textile sector.

Money from rags

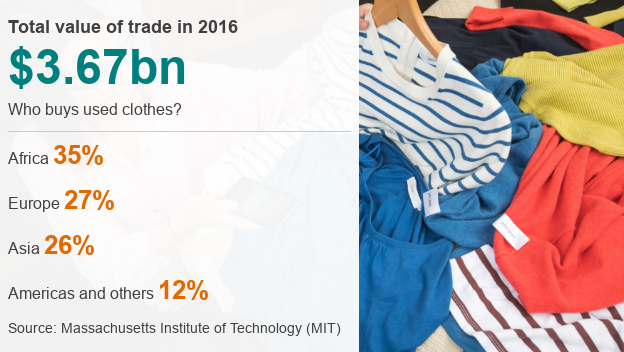

There has long been a global trade in second-hand clothes, handed in to charity shops in wealthy Western nations and then sold on to traders in Africa and elsewhere in the world.

This is big business. Some of the wholesale traders in African nations have established highly profitable businesses.

However, some African countries have had enough of hand-me-downs and the impact they are having on local industries.

In 2015, member states of the East African Community (EAC), external, which comprises Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, announced they would ban second-hand imports from 2019 to protect their own clothing manufacturers.

East African countries, which account for 13% of the global market in second-hand textiles (worth a total of $274m (£208m) in 2015), began imposing tariffs.

Rwanda and US at loggerheads

But then, under pressure from the United States, countries in the EAC reduced tariffs and withdrew the proposed ban. Rwanda, however, refused to back down.

And in March 2018, the US temporarily suspended Rwanda from an arrangement allowing sub-Saharan countries preferential access to the US market.

See more stories and videos like this

But Rwanda stood firm and maintained its import tariffs, saying it wanted to build up its own "Made in Rwanda" textile industry.

And, as a result, it lost some of its duty-free privileges on exports to the US.

However, the planned import ban by East African countries wasn't supported by everyone in those countries, particularly those whose livelihood depends on the sector.

Changes to world trade policies

The argument over the effect of the second-hand clothes business needs to be put in a broader context.

African countries, under pressure from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund over many years, have undertaken structural adjustment programmes that have effectively reduced subsidies designed to protect their home-grown industry and therefore opened up their markets to foreign trade.

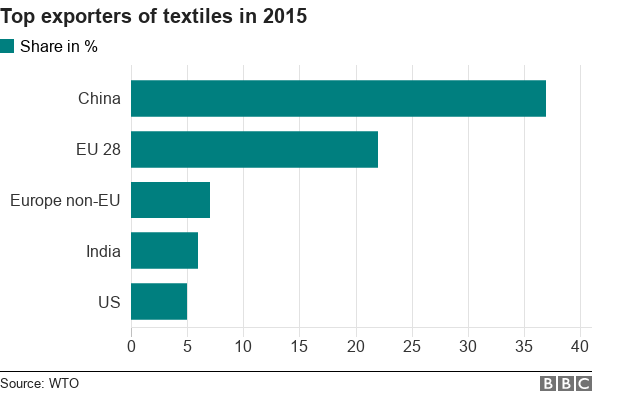

This has made it much easier for European, American and Asian clothes manufacturers to export to the African continent.

Another important factor has been the removal of quotas for the textile industry under what was known as the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA), originally set up in 1975.

One of its principal aims was to protect producers in the US and the EU from lower-cost garment exports from Asia - but the agreement also had the effect of enabling smaller African exporters to get favourable access to US and European markets.

This agreement was gradually phased out, finally ending in 2005. This allowed Asian producers, along with those from the US, EU and Canada, to flood African markets with both new and second-hand clothes.

By 2005, the International Textile, Garment and Leather Workers' Federation estimated that more than 250,000 jobs in the sector had been lost in Africa.

Textile industry decline

There is a lack of detailed recent statistics for textile industries around the world.

However, a 2006 German study looking at the industry in sub-Saharan Africa, external reported that Ghana had suffered a decline in textile output of about 50% between 1975 and 2000.

Cheaper imports from Asian producers have also had an impact

In Zambia, employment in the textile sector had dropped from 25,000 in the 1980s to below 10,000 in 2002, it said.

There are other factors apart from changing trade dynamics and the trade in second-hand clothes.

Conflict and political stability have also played a part in some places.

For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, devastated by years of civil war, there was a more than 80% drop in textile production between 1990 and 1996.

What is the impact of imposing tariffs?

Since Rwanda imposed its tariffs on second-hand clothing imports, government data shows the value of its home-grown textile industry has increased from about $7m to $9m.

It's tricky to point to a direct link between the new tariffs and this increase, however, because there's also been outside investment in the industry.

Chinese manufacturer C&H Garments opened its first factory in Rwanda in 2015. And it now employs nearly 1,400 Rwandans, who produce items such as police and army uniforms.

But the textile manufacturing industry in Rwanda is relatively small in terms of the overall economy.

It is also worth saying that the second-hand clothes sector is a big employer in East Africa, both directly and indirectly, largely in sales and distribution.

So while second-hand clothes imports do undercut local producers and traders, they also provide employment - and local textile producers are up against cheap, efficient producers in Asia and elsewhere.

Finally, it's worth bearing in mind that although the global trade in used clothes is still big business, it is now showing signs of decline as trade patterns and consumption habits change.

- Published2 March 2016