How super-rich tourism may help the planet

- Published

On a remote tropical island in the Indian Ocean, a man in a woman's wig has been hiding in a bush for hours. Armed with an air rifle, he plans to kill the island's last three surviving specimens of an exotic bird.

This, unlikely as it might appear, is the current front line in a conservation revolution.

"Normally, you see environment and development at each other's necks," the Seychelles tourism minister, Didier Dogley tells me. "Here we have pioneered an approach that turns it the other way round."

The Seychelles model, as Mr Dogley calls it, claims tourist development doesn't damage the environment, it positively improves it.

It sounds a little far-fetched. The demands of the global traveller can place a heavy footprint on the perfect white sands of a fragile eco-system like the Seychelles. For even the most responsible tour operator, it is usually a question of mitigating the damage.

North Island is an exclusive holiday haven for the very wealthy

The seeds of the idea washed up on a number of Seychelles islands in the 1990s, notably North Island, bought by the ecotourism pioneers Wilderness Safaris in 1997.

The company had strong green credentials having established safaris across southern Africa that diverted tourist revenues to help save dozens of critically endangered species and fund conservation projects.

Now their attention had shifted to one granite dot in the island group.

North Island was a mess. It had been abandoned as a coconut plantation. Rats had killed off the wedge-tailed shearwater and the white-tailed tropicbird, seabirds that had nested there in vast numbers.

Once the home to thousands of giant tortoises, now just three remained. Invasive flora and fauna had crowded out the natives, including rare endemic species, found only in Seychelles.

North Island's population of giant tortoises had been reduced to just three

Wilderness decided to restore the island to its former natural glory and get super-rich tourists to pay for it.

It was an audacious plan. Eleven exclusive luxury villas, each costing guests several thousand euros a night, were hidden among the Takamaka trees and coconut palms along the white sand beaches.

The hope was that the world's wealthiest would be wooed by a unique feel-good factor: fabulous luxury, total privacy and the quiet satisfaction of doing something positive for the planet.

Rumour has it that George and Amal Clooney have been guests at least once. David and Victoria Beckham are also said to have stayed. We do know the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge spent their honeymoon on North Island.

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge honeymooned on North Island

"Instead of building a hotel and then beautifying the place with exotic things, the hoteliers and investors in small islands like North Island have twisted the whole thing around," Mr Dogley says.

"They remove the exotics and bring in the endemics and natives, making that the attraction for the tourists that stay on the island. I think this is an incredible model."

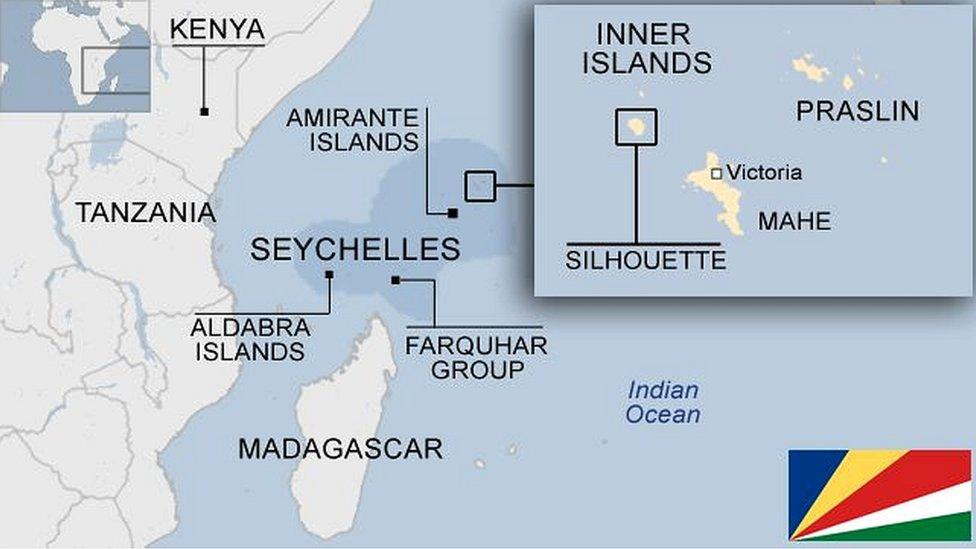

The Seychelles

111 islands in the Indian Ocean

Population: 95,000

Over 40% of the land now protected by legislation

A marine national park and protection zones will cover an area of ocean about the size of Britain

The tourism ministry is now promoting a "one island, one hotel" policy. A hotel business can apply for exclusive access to a small corner of an island otherwise designated a Seychelles nature reserve. The hotel must then spend part of its turnover on restoring and improving the island's ecology.

"Something on this island is mystical. At a certain time it hits you," says Andre Borg, a veteran of global hotel chains who does not strike you as an eco-warrior.

"I was career-driven. Then I arrived as general manager at Hilton Labriz on Silhouette here in Seychelles and I thought, how am I going to survive on this island?"

Mr Borg says he found himself listening to the voice of the island. And the message, he reckons, was clear. "You have to follow what it says. The future is sustainability."

Hotel operators in the Seychelles are looking increasingly towards sustainability

He ordered the end of plastic water bottles at his hotel, following the lead of the eco-hotel on North Island. Rather than pay £4 a time, guests now fill reusable bottles for free.

Hotel chains operating in Seychelles accept they now compete on how green they are, funding coral nurseries and environmental rangers.

"There are just 50 sheath-tailed bats in the world," Mr Borg says. "Twenty-three of them live in a cave on this island. I have never seen them, but we have to protect them."

Protecting and enhancing the environment will require commitment and there are inevitable questions as to what happens when the warm green rhetoric of a hotel's marketing department no longer satisfies the cool bottom-line demands of the finance department.

The experience of North Island is a reminder that making a tangible difference can take decades. In the 1990s, the first priority was to de-rat the island, but it took two attempts and eight years before the owners could announce in 2005 that North Island was, finally, rat free.

Many species, including the Seychelles skink, are unique to the islands

Strict controls still exist to stop a reinvasion. There is no jetty: every box and case coming ashore is carried by hand up the beach and into a series of sealed rooms where each is checked individually.

Without rats, and also now without the alien barn owls and cats foolishly introduced by plantation owners to control the rats, native birds are returning. Endemic species are being re-introduced, part of what is called the Noah's Ark project.

The Seychelles white-eye, a charming and curious little bird, remains one of the rarest in the world. After North Island was declared rat free, 25 were brought from one of the few remaining colonies. Last year the island population had reached at least 140 with signs numbers are still rising fast.

The white-eye's success is not just down to de-ratting. It is also about dealing with one of the most invasive and aggressive birds on the planet.

The invasive common myna has been all but eradicated on North Island

The Indian myna has been renamed the common myna because it has spread far beyond its indigenous territory, killing and displacing native birds as it goes.

Introduced to the Seychelles by pirates and traders, who admired its parrot-like ability to mimic speech, it has become such a menace that an international fight back has begun.

A publicity-shy former British undercover policeman is among the myna eradicators travelling the world helping people outwit the birds.

"He used traps and decoys initially, but the birds are smart," North Island conservation manager Tarryn Havemann explains.

"We gradually got the numbers down from around 700 to just three, but we cannot eradicate the final few. Sometimes they come to my window just to mock me!"

The Seychelles white-eye is one of the rarest birds on earth

And that is why a man has been hiding in a bush wearing a woman's wig. Experts advise that myna birds can recognise faces, clothing and even hairstyles, so better to track them in disguise.

There is urgency here. Only when the last three have been killed will North Island be allowed to reintroduce other endemic birds, including the incredibly rare Seychelles magpie robin.

Tropicbirds and shearwaters are breeding on the island once more. Green turtle nest numbers have increased six-fold in 20 years. Around a hundred giant tortoises now plod their way amiably around the plateau.

More than 30% of the land has undergone some rehabilitation, but it could take 50 years simply to remove the rampant coconut palms from the island. "Will conservation still be sexy then?" Mrs Havemann asks.

One must hope. Government, businesses and environmentalists all seem to be singing the same tune for now, an infectious melody that can be heard in the chirruping of the white-eye, the rustling leaves of the Takamaka tree and the crash of the Indian Ocean on the fragile coral reefs of Seychelles.

Once you have heard it, it is a song you struggle to get out of your head.

- Published21 July 2023