Disability in Africa: 'I'm no longer ashamed of my disabled daughter'

- Published

Agnes Mutemi with her 14-year-old daughter Nambia

When Agnes Mutemi discovered that her first-born daughter Nambia was mentally ill at the age of two, her first reaction was to be ashamed. She remained in denial for several years until she found a school which specialised in caring for children with disabilities.

The 38-year-old mother of three says that most of her discomfort was triggered by the gawping, stares and ill treatment she faced on a daily basis.

"During the first years, I often used to ask myself why I had been given such a child.

"It was tough walking around with my child because of the looks I got," says Ms Mutemi, who lives in Katoloni village in eastern Kenya.

Agnes says Nambia had asphyxia, a condition that occurs when a baby is deprived of oxygen during the birth process.

As a result, Nambia's limbs were weakened and her mental development affected.

'Healed'

After numerous physiotherapy sessions, Agnes enrolled her daughter in an early childhood education school when she was three.

"It was only after Nambia spent six years in nursery school and still couldn't do basic things that I realised something was wrong," says Agnes, adding that the cost of medical care for a mentally ill child in Kenya is very high.

"I had wanted my daughter to have a career - to become a teacher, a professor or a doctor, but that was not to be."

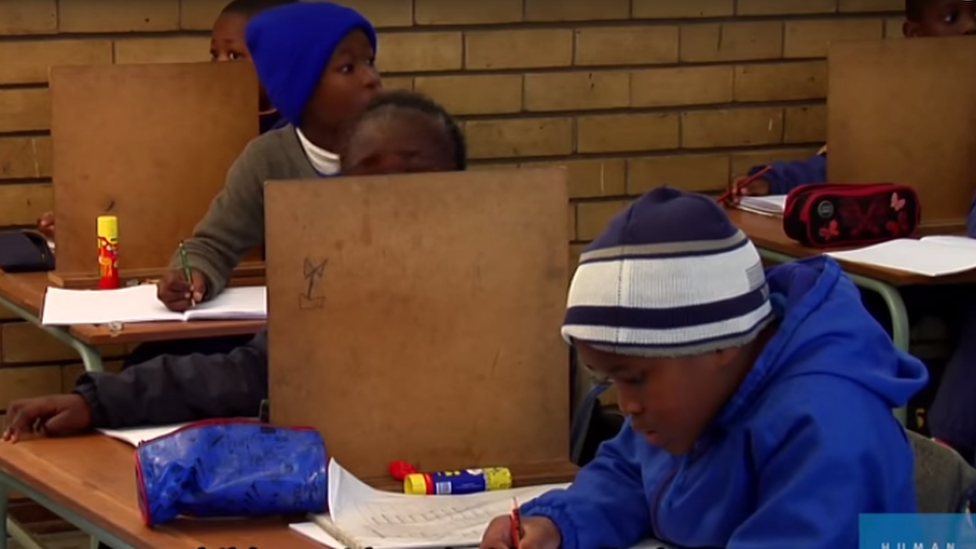

Nambia loves to play with her classmates

At one point, Agnes even decided to stay at home with Nambia since she wasn't being accepted in "normal" schools.

But what really changed Agnes' life was meeting an old friend who advised her to take her child to a special school.

"After seeing changes in my daughter I finally accepted her condition.

"I'm no longer in denial," she said.

Nambia, now aged 14, goes to the Machakos Unit for the Mentally Challenged, staffed by local and foreign volunteers from British development charity VSO.

She has learning disabilities, but this has not dampened her high-spirited nature and she loves playing with her classmates.

And despite being largely non-verbal, Nambia is an active teenager and has developed a strong bond with her mother.

Nambia is among the more than one billion people in the world living with some form of disability.

These activists wanted President Kenyatta to include disabled people in cabinet

The World Health Organization says about 15% of the world's population have some form of disability, external and the prevalence is higher for developing countries.

According to Unesco, 90% of children with disabilities in developing countries do not attend school., external

In Kenya, there were 1,341 special units and 114 public special schools in the country in 2008, according to a 2009 report by the ministry of education,, external which is the most recent available.

But this is not enough and not every disabled child gets the same care as Nambia.

The 2009 report showed that about 90% of Kenyan children with disabilities were either at home or enrolled in regular schools with minimal or no specialised care.

'My son is my everything'

And life is also hard for disabled parents, who have to provide for their children.

Kevin Momanyi, 10, wheels his mother Irene Kerubo to her shop every morning before going to school

Irene Kerubo, 32, depends on her 10-year-old son to wheel her to her shop every morning before he goes to school in Kenya's Nakuru County.

This has become a daily routine for Kevin Momanyi, whose mother was struck with polio when she was just four, leaving her paralysed from the waist down.

"My 10-year-old is my everything.

"He performs all the daily chores and helps me put food on the table by wheeling me to work," says the mother of four.

This situation has relegated her to a life of poverty and struggle.

You may also be interested in:

'Ageing populations'

And so there is cause for concern as the latest World Report on Disability (2011), external shows the number of people with disabilities is rising.

Ageing populations, and a worldwide rise in chronic health conditions linked to disability - like cardiovascular diseases and mental illness - are the reasons why, the report says.

The disabled also tend to have less access to health care services.

But all is not doom and gloom.

David ole Sankok says he asked President Kenyatta to try writing his name by holding his pen in his mouth

Former National Council for Persons with Disability Chairman David ole Sankok says that, compared to other African countries, Kenya has achieved milestones.

"The disabled don't pay taxes and import vehicles tax-free, and sign language is the third national language, with news bulletins being aired with sign language interpreters," says the nominated MP for persons with disabilities.

Mr Sankok said President Uhuru Kenyatta directed that exams for the disabled be adaptable after the lawmaker asked the head of state to write his name by holding a pen using his mouth and he was only able to write one letter on a whole piece of paper, with a lot of difficulty.

In August, President Kenyatta said he would ensure the disabled were appointed to senior positions in public service.

Agnes says it pains her that it is difficult to point to a definite future career for daughter.

However, she is happy that through going to a specialist school, Nambia's speech is improving, she is learning basic subjects like mathematics, English and science and participates in ball games, bead work and making liquid soap.

But she says that African governments should do more for disabled children by providing them with life skills that would enable them to earn a living.

- Published27 September 2018

- Published17 June 2016

- Published18 August 2015