On the trail of Uganda's illegal 'beauty-cream' smugglers

- Published

Jane Ndagire used skin-lightening creams on her face for several years

Jane Ndagire blames illegal skin-lightening products, smuggled into Uganda over a dangerous border, for ruining her complexion.

She was approaching her 40s, when the women in her circle started hinting at how they could look younger.

Someone mentioned a cream called Caro Light saying a close friend had a glow on her face within a week of using it. Ms Ndagire wanted in.

"Within three days, I could see a difference. My face had this radiance I had never seen before. I applied it all over my body," she says.

Several months in, she started to feel the heat of the sun more, and the skin on her cheeks felt taut. Her supplier recommended mixing the lightening cream with petroleum jelly.

"My complexion became too light. But I could not reverse the effects. Then I started getting pimples, which take long to heal.

"When I get a small bruise, it takes weeks to dry up. My skin feels flabby to the touch," she adds, staring at her hands which are visibly darker than her face.

It is easy to pick up banned creams at cosmetics shops in Uganda's capital

Ms Ndagire, now 45, has raw red cheeks. She finally quit lightening her skin five months ago.

"I didn't know there would be long-term side effects. Sometimes I feel like covering my face. I just pray that I didn't damage my skin to the extent of getting cancer."

'My clients ask for banned products'

The products Ms Ndagire used, along with more than 100 others, have been banned in Uganda since 2016.

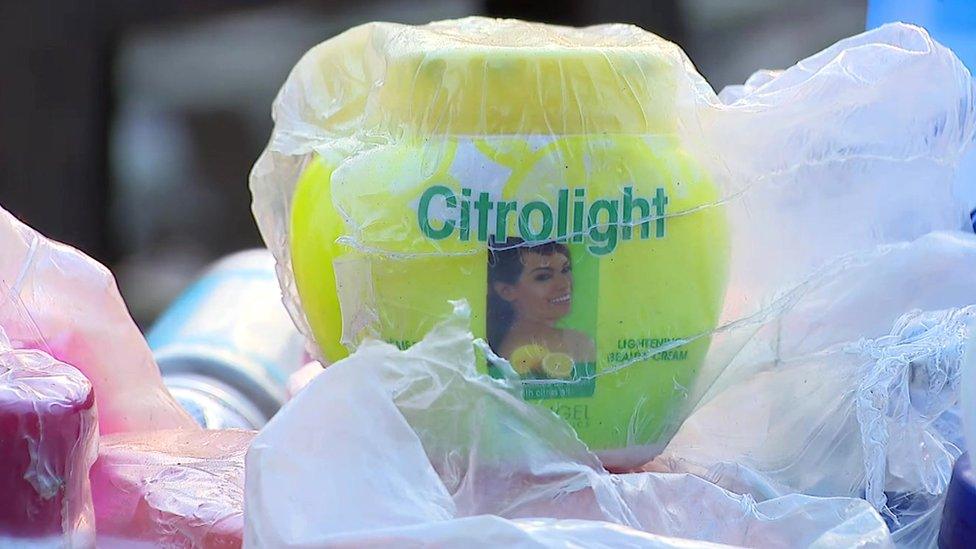

This pot of illegal skin-lightening cream sells for a little more than $1 in Kampala

All of those on the list contain mercury and hydroquinone, which some studies have linked to damaging health side effects, according to the government, external. And yet, they are widely available in the country.

I go shopping in Nakulabye, not far from the centre of the capital, Kampala, and every cosmetics shop stocks them.

I make a beeline for one, and ask for Caro Light. The owner advises me to buy some oil too, but also to try out Perle Claire, which is also banned.

"You have to get a bit of each and mix. Use the oil if your skin is too dry," she counsels.

I go all out, buying a 300ml pot of Caro Light at $2 (£1.50), a 150ml pot of Perle Claire and a 120ml pot of Citrolight, another product on the prohibited list, at just over $1 each.

Individual smugglers can earn $1 for every trip they make across the border

In my little collection are products manufactured in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ivory Coast. Some of them declare on the label that they contain hydroquinone.

The shop owner is aware that the cosmetics are banned, but she is not worried as it is good business. "My clients ask for them," she says.

Tonnes of the banned skin-lightening products get into Uganda every year, mostly through porous points along the border with DR Congo.

Jungle smugglers

"The entire border has countless smuggling routes. We are the closest neighbour to the source [in the DR Congo], so all the products headed for the rest of East Africa come through here," says Dicksons Kateshumbwa, the Ugandan Customs Commissioner.

His officers intercepted 61 illegal consignments in 2017, and 93 in 2016, across the whole of the country.

Smugglers create false bottoms in jerry cans to get the cosmetics across the border

At Mpondwe, a border crossing in the west, the store at the customs office is filled to the roof with 1,500 boxes impounded in the past seven months.

In March this year, two lorry loads of the beauty products were incinerated at a government facility near Kampala.

Since then, 16 tonnes of impounded cosmetics have accumulated at the customs headquarters in the city. Elsewhere, 8.5 tonnes are stored in Mbarara to the west and 1.6 tonnes in Pakwach to the north-west.

More on skin lightening:

The cosmetics rarely come in bulk deliveries. Carriers, who earn about $1 per trip, bring them across the border box-by-box or sack-by-sack.

They often come concealed in sacks of green bananas, and even in plastic jerry cans with false bottoms that are cut and sewn up.

In Mpondwe, the carriers embark on a risky journey, crossing a river and hauling their load through winding village paths in the foothills of the Rwenzori mountains.

Pleading for mercy

I am embedded with a team of law enforcement officers under the Uganda Revenue Authority.

Customs officers search for smugglers in the Rwenzori mountains

It is along one of these paths that we come across a small group young men with boxes of the beauty products. Two of the carriers spot us, drop their load and run downhill. The uniformed officers try to give chase.

The 25-year-old Congolese man is sweating profusely; perhaps from the climb or nervousness, or both.

He claims that he runs a one-man business; bringing the goods across the border, and transporting them by commuter taxi to buyers in Kampala. But the officers suspect he is trying to protect the rest of his network.

Upon further interrogation, he says that he is aware what he is doing is illegal. Twenty of his boxes have been impounded in the past.

He pleads for mercy, saying he is a father of two and the sole breadwinner for his family. Good money can be made, as a carton selling for $40 on the DR Congo side will be worth more than $70 in Kampala.

Today though, his goods will not be making it to the market. They are confiscated, but the man is let go as the authorities are only interested in detaining the big-time smugglers.

There are just eight officers in the team charged with gathering information and intercepting all illegal goods coming into the country. The number is not sufficient to break the sophisticated smugglers' networks.

Many homes in the Mpondwe border area, and in the main regional town of Kasese, are used as transit warehouses.

Hidden in child's bedroom

One morning, the team leader receives a tip-off that a house in a village about 20 minutes away is harbouring the beauty products.

Earlier this year, officials found a truck with boxes of cosmetics buried in the sand it was transporting

The residents do not seem in the least surprised at seeing the investigators at their door. They ask to come in, and head straight for what seems to be the children's bedroom.

The lady of the house is questioned about the incriminating cargo on the floor.

"Some young men brought them here on a motorcycle, they requested me to keep them, and they rode off," she answers.

The next day, information about a house in Kasese town comes in. It takes about 30 minutes of driving around a semi-slum neighbourhood before locating the right house. There is a trail of something having been dragged on the ground, leading out of the compound.

'I almost died from skin-whitening creams'

It seems someone tipped the criminals off, a sign that some law enforcement officers might be colluding with the smugglers.

Nevertheless, the customs personnel question the woman in the lavishly furnished home, who vehemently pleads her innocence.

But they wear her down, and she pulls a backpack from under a bed, packed to the seams with illegal creams. Elsewhere, little packs are hidden in a laundry basket, in suitcases, behind the music system, even in the fridge.

"She was trying to spread the risk," one of the officers quips, stuffing the lot into a plastic bag. Once again, the goods are seized, but no-one is arrested.

Tackling demand

At a temporary checkpoint on the highway later that night, the army and police stop lorries piled high with manufactured goods, they also target passenger buses bound for Kampala.

A sack full of the cosmetics is flung out of the window of one of the buses waiting to be checked.

The authorities in Uganda have burnt tonnes of the seized cosmetics

"As long as there is demand for something illegal, you face a major challenge fighting it. But we are approaching it from several angles," says Commissioner Kateshumbwa.

"We try and stop the products from getting into the market. And we prosecute the smugglers; in 2017 we brought 42 cases before court."

And yet, thousands of boxes continue to slip past the authorities.

Ms Ndagire, who is now seeing a dermatologist, wants the government to inform Ugandans about the dangers of these cosmetics in much stronger terms than it has up to now.

To her, changing attitudes would reduce demand for skin lightening, and save women from the trap she fell into.

- Published1 January 2013

- Published6 August 2018

- Published6 August 2018

- Published26 April 2023