Letter from Africa: Why I was sentenced to 5,000 years in jail

- Published

In our series of letters from African writers, Rodney D Sieh, editor of Liberia's FrontPageAfrica, reflects on what his career says about the state of journalism in West Africa.

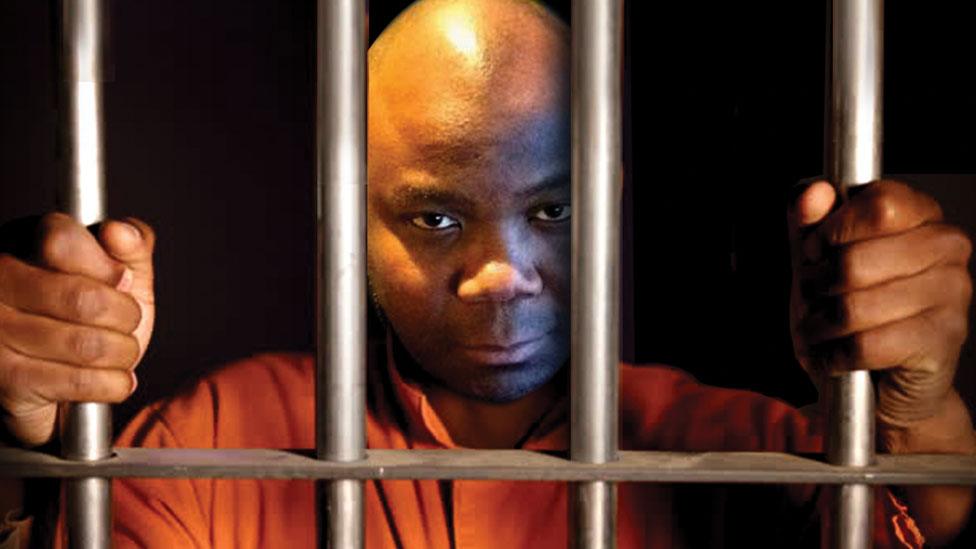

My claim to infamy was being sentenced to 5,000 years in prison for failing to pay libel damages of $1.6m (£1.2m) won by a former minister who sued my paper after we published the findings of a government audit.

It had found that funds worth $6m intended to combat an army-worm epidemic were unaccounted for.

I served four months in 2013 in the notorious Monrovia Central Prison, where I was thrown into a cell with murderers, armed robbers and petty criminals.

The prison, built in the capital city to hold 200 prisoners, has more than 1,000 inmates. Nearly half of them have been detained without trial.

Over the years, it has built a reputation as a haven for hard-core criminals and where critics of government are sent to be taught a lesson.

Rodney Sieh was freed after four months following an international outcry

I remember the head of the facility trying to convince me to give the menu of the day a try: a plate of beans and rice with no meat or fish - and maggots squirming around the cart on which the food was stacked.

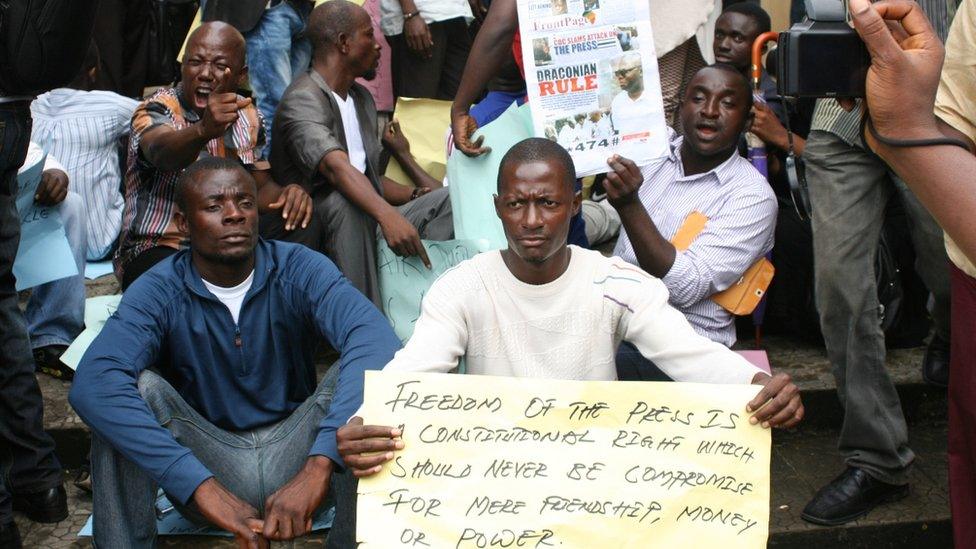

It took the might of an international outcry, massive protests from supporters and sympathisers and an op-ed in the New York Times to force the government of then-President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to get me out of prison, external.

Young boys and rifles

My ordeal is just one example of the difficulties journalists face on a continent often dominated by an elite uncomfortable with criticism.

Just look at what has happened over the past few decades: scores of my colleagues have been killed, maimed and persecuted; newspapers have been shut down and fear permeates our work environment. Others live in exile, disconnected from their families.

As a youngster growing up in Monrovia's hard-knock neighbourhood of Broad Street Snapper Hill, I saw a lot of events unfold.

Whether it was the rice riots of 1979, or the bloody coup one year later that brought Master Sergeant Samuel Kanyon Doe to power, images of violence defined my adolescence.

This backdrop was just one of the motivations that helped to prepare me for life as a journalist.

What happened in Liberia's civil war?

1989: Charles Taylor starts rebellion against President Samuel Doe

1990: Doe horrifically killed by rebels

1997: Civil war ends after death of some 250,000 people. Taylor elected president

2012: Taylor convicted of war crimes in neighbouring Sierra Leone

My late grand-uncle Albert Porte was a pioneering pamphleteer, crusader and journalist who is famously remembered for standing up to a corrupt system and engaging in a now historical series of letter exchanges with late President William VS Tubman - taking him to task for purchasing a personal yacht at a time when many were struggling to feed themselves.

When Charles Taylor started his rebellion on the eve of Christmas in 1989, I watched as friends, families and loved ones I grew up and went to school with died like flies around me.

I saw young boys holding rifles bigger than themselves and streams of families carrying what they could as they fled their homes. Some of our neighbours who stayed behind to protect their homes and belongings lost their lives - killed for either belonging to the wrong ethnic group or simply because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The following year, not long after Doe was captured and killed by rebels, I joined my uncle Kenneth Best in The Gambia, where he had started the Daily Observer newspaper.

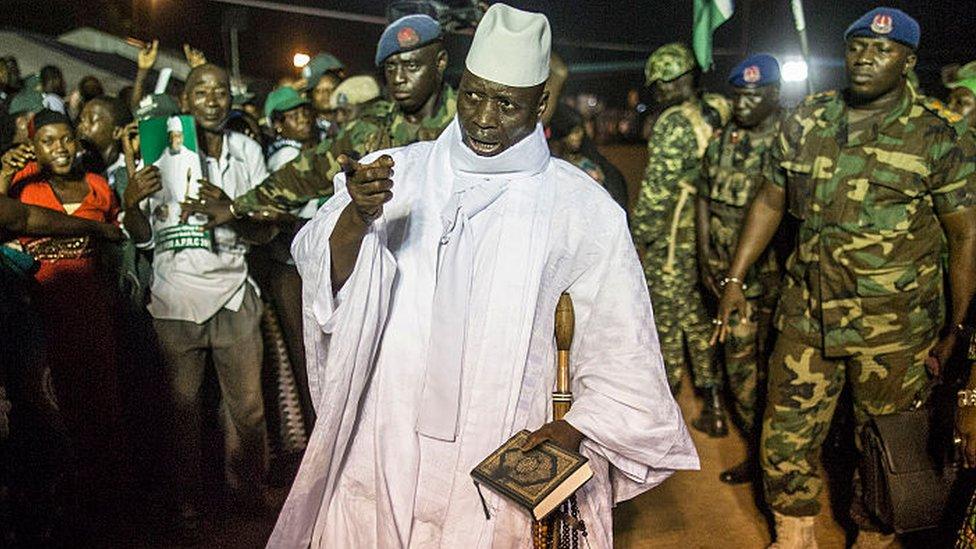

Yahya Jammeh was intolerant to criticism when he led The Gambia

In 1994, when Yahya Jammeh seized power in The Gambia as a 29-year-old army lieutenant, everything again came crashing down.

Now a working journalist, I did manage to score the first interview with Mr Jammeh, in which he brushed off comparisons to Doe and pledged that there will be no dictatorship in The Gambia.

He went on of course to rule for 22 years until his fall at the ballot box, going into exile in January 2017 after regional troops made his attempt to hold on to power untenable.

Not long after the 1994 coup, I watched as Mr Jammeh deported my uncle following a controversial interview with the New York Times. Later, I too became a target and had to go into hiding before fleeing to the UK and then the US, where I honed my skills working for several newspapers before starting the online FrontPageAfrica, external.

Tackling the FGM taboo

I soon realised that my country needed me back home.

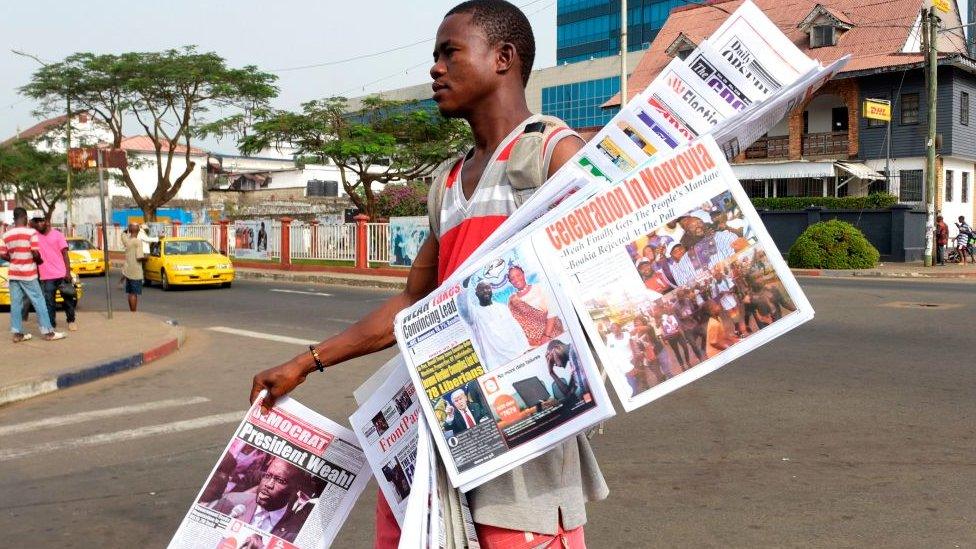

With the war over and the holding of a successful election in 2005 that brought Ms Sirleaf to power, I returned to Liberia in 2007 to launch the print edition of FrontPageAfrica.

It appears that many of those who had been held to account by our work saw my return home as an opportunity to take revenge. I survived arson attempts on my newspaper's office and a slew of lawsuits followed, two of them landing me in jail.

Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, in power for 12 years, outlawed FGM on her final day in office

Running a daily newspaper comes with great risks, even when it comes to reporting issues such as female genital mutilation (FGM), prostitution, and human rights.

Mae Azango, one of our fiercest journalists, best known for her reporting on FGM, went undercover in 2010 to expose the traditional practice, which is often conducted in secret on young girls.

FGM is now been banned in Liberia - outlawed by Ms Sirleaf on her last day in office in January.

Azango, and another female reporter, also braved the night to shadow prostitutes, who shared their ordeals about the dangers that come with giving up their bodies for as little as five Liberian dollars ($0.03, £0.02) a time.

'I refuse to back down'

The challenges of bringing these stories to light are enormous. Reporters take risks for little pay as newspaper owners struggle to pay staff and keep the generator running because of an unstable electricity supply.

Papers often rely on advertising for their revenue - and the government is the biggest advertiser

Advertising is the biggest revenue earner, but the government is often the largest advertiser - and can boycott outlets at whim.

Over the years, I have worked under several West African regimes, so I know first-hand how authoritarian leaders bully and undermine the media.

Had I succumbed, I would by now have been among the hundreds of journalists in the forgotten pages of the Committee to Protect Journalists' annual press report.

Had I backed down, perhaps I would still be serving a 5,000-year jail sentence for criminal libel, a law I intend to fight for as long as I live.

I have come this far because I refuse to back down and I refuse to give in.

Rodney D Sieh is the author of of the forthcoming book Journalist on Trial - Fighting Corruption, Media Muzzling and a 5,000-Year Prison Sentence in Liberia

More Letters from Africa

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published22 January 2018

- Published21 May 2013