African migration 'a trickle' thanks to trafficking ban across the Sahara

- Published

The security forces in Niger now patrol on the look out for traffickers

The number of migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean for Europe has been dropping and that is partly because of tougher measures introduced on the migrant routes, as Mike Thomson reports from Niger.

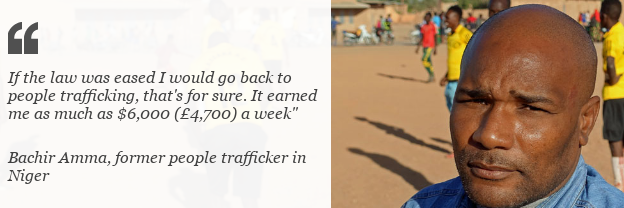

In a small dusty courtyard near the centre of Agadez, a town on the fringes of the Sahara desert, Bachir Amma, eats lunch with his family.

A line of plastic chairs, clinging to the shadow of the mud walls, are the only visible furniture.

Mr Amma, a former people smuggler, dressed in a faded blue denim shirt and jeans, has clearly known better days.

"I stopped trafficking migrants to the Libyan border when the new law came in.

"It's very, very strict. If you're caught you get a long time in jail and they confiscate your vehicle.

"If the law was eased I would go back to people trafficking, that's for sure. It earned me as much as $6,000 (£4,700) a week, far more money than anything I can do now."

Traffickers jailed

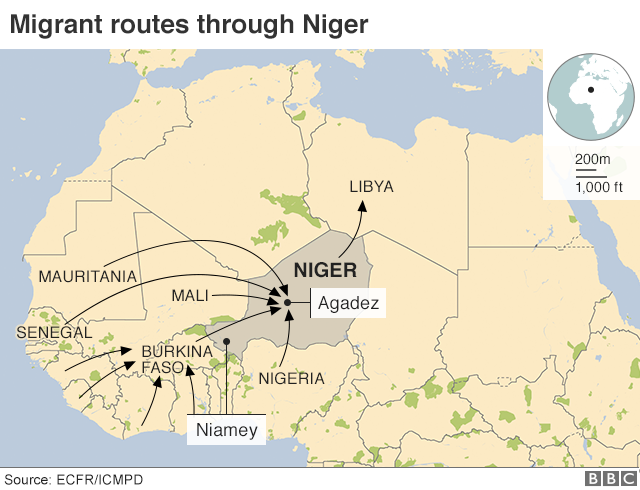

The law Mr Amma mentioned, which banned the transport of migrants through northern Niger, was brought in by the government in 2015 following pressure from European countries.

Pick-up trucks take the migrants from Agadez across the desert into Libya

Before then such work was entirely legal, as Niger is a member of the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) that permits the free movement of people.

Police even provided armed escorts for the convoys involved. But since the law was passed many traffickers have been jailed and hundreds of their vehicles confiscated.

Before 2015, the Agadez region was home to more than 6,000 people traffickers like Mr Amma, according to figures from the UN's International Organization for Migration (IOM) .

Collectively they transported around 340,000 Europe-bound migrants through the Sahara desert to Libya.

Migration in reverse

Since the clampdown this torrent has become a relative trickle.

In fact, more African migrants, who have ended up in Niger and experienced or heard of the terrible dangers and difficulties of getting to Europe, have decided to return home.

This year alone 16,000 have decided to accept offers from the IOM to fly them back.

A large and boisterous IOM-run transit centre in Agadez is home to hundreds of weary, homesick migrants.

In one large hut around 20 young men, from a variety of West African countries, attend a class on how to set up a small business when they get home.

Among them is 27-year-old Umar Sankoh from Sierra Leone, who was dumped in the Sahara by a trafficker when he was unable to pay him more money.

"The struggle is so hard in the desert, so difficult to find your way. You don't have food, you don't have nothing, even water you can't drink. It's so terrible," he said.

Now, Mr Sankoh has given up his dreams of a better life in Europe and only has one thought in mind: "I want to go home.

"My family will be happy because it's been a long time so they must believe I am dead.

"If they see me now they'll think, 'Oh my God, God is working!'"

Coast guards intercept vessels

Many thousands of migrants who make it to Libya are sold on by their traffickers to kidnappers who try and get thousands of dollars from their families back home.

Thousands of migrants are still losing their lives trying to reach Europe by boat

Those who cannot pay are often tortured, sometimes while being forced to ask relatives for money over the phone, and held in atrocious conditions for months.

With much of the country in the grip of civil war, such gangs can operate there with impunity.

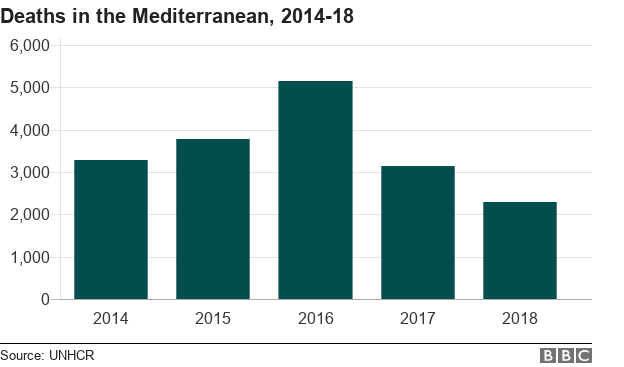

In an effort to curb the number of migrants making for southern Europe by boat, thousands of whom have drowned on the way, coast guards trained by the European Union (EU) try and stop or intercept often flimsy vessels.

Those on board are then taken to detention centres, where they are exposed to squalid, hugely overcrowded conditions and sometimes beatings and forced hard labour.

Legal resettlement offers

In November 2017, the EU funded a special programme to evacuate the most vulnerable refugees in centres like these.

Under this scheme, which is run by the UN's refugee agency (UNHCR), a little more than 2,200 people have since been flown to the comparative safety of neighbouring Niger.

There, in a compound in the capital, Niamey, they wait for the chance to be resettled in a European country, including the UK, as well as Canada and the US.

So far just under 1,000 have been resettled and 264 accepted for resettlement.

The rest await news of their fate.

More on EU migration crisis:

Abdul Karim, a young man from Somalia, arrived at this compound just over three weeks ago after six terrible months in the clutches of a Libyan kidnap gang

"When I was in Libya I didn't see the sun for six months because we were kept underground.

"It was so difficult to breathe and if you talked they would kill you. There was a lot of people, they died in there," he said.

Finally, Mr Karim told me, he and nine other hostages managed to overpower one of their guards and escape, though two were shot dead on the way out. They were then rescued by police who notified UNHCR.

Healing through music

Among the most vulnerable refugees evacuated from Libya are unaccompanied children.

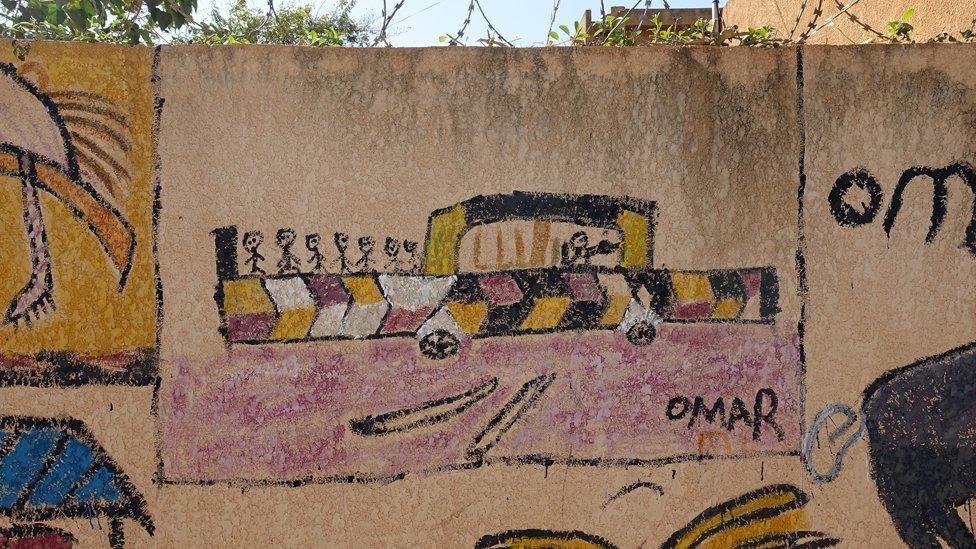

A child's drawing at a migrant rehabilitation centre depicts part of the desert journey

Many have experienced similar horrors to Mr Karim and have brought memories of their long running nightmares with them to Niger.

But a rehabilitation centre in the capital is trying to address these.

The arresting tones of an electric organ mingle with gentle drum beats and the strumming of guitars in a small dusty room on the outskirts of Niamey.

Around a dozen teenage migrants sit transfixed as they are patiently shown the basics of composing a melody.

Music therapy is helping migrants who have returned from Libya deal with the trauma

One boy at the back stares into space, his troubled mind evidently elsewhere, but most eyes remained glued to their young Senegalese music teacher, Adel.

He tells me that many of these young migrants find it hard to articulate their thoughts, their traumas trapped deep inside, but believes that learning an instrument will help them.

"Music doesn't have limits. And even if you are sad, music can express it. So if they learn music it's like a voice for them to talk," Adel said.

'Forced to drink urine'

During a break in the lesson, which was organised by UN children's charity Unicef, I spoke to the boy at the back of the room whose attention had seemed elsewhere a little earlier.

The 16-year-old, who did not want me to use his name, revealed what happened to his group when they were crossing the Sahara.

When their water ran out they were forced to drink their own urine and the traffickers, who kept asking for more money, beat them all and repeatedly raped the women.

But it seems that sessions like this one are slowly helping him recover.

"When I first came to Niger I kept thinking of bad things, like when one of my friends died while we were crossing the Sahara.

"But I have kept busy and the music is helping me forget these bad things."

For tens of thousands of other refugees and migrants still in Libya, whether they are in squalid detention centres or being held by kidnappers, the nightmare continues.

Little chance of desert rescue

Although there has been a big drop in the number of African migrants heading north to Europe, the risks are now worse than ever for those who continue to make this journey.

The law banning the transport of migrants in northern Niger has led many traffickers to take dangerous back routes to avoid being arrested by police patrols.

These take them further from water holes into areas plagued by armed groups and strewn with land mines. The chances of being rescued in such desolate, hostile places is often extremely remote.

The vastness of the Sahara desert, an area around four times the size of the Mediterranean, also means that the bodies of many migrants who have perished there may never be found.

Once the pick-up trucks leave Agadez they need to navigate through the desert

UNHCR's country representative in Niger, Alessandra Morelli, believes that many more migrants have lost their lives in this merciless sea of sand than have drowned in the Mediterranean.

"We, the international community, the UNHCR, say that for every death in the Mediterranean there are at least two in the Sahara, unknown and anonymous.

"Definitely the routes are more dangerous and more costly."

'Smuggling makes money'

Back in Agadez, as the scorching sun sinks from the sky, a young man, his face partially concealed in the hood of a white fleece, is on his phone drumming up business.

Ibrahim, who does not want his real name published, is preparing for his next trip through the Sahara to Libya.

His task now is to get enough migrants to fill the pick-up truck he drives for a local people trafficker.

Despite the restrictions Agadez will remain a place for migrants to head for

Far from being worried about the clampdown which forces him to take longer, more dangerous back routes, Ibrahim smiles. Because he is paid by the day, he is now making more money than ever.

"In the past the journey to Libya would take three days but now it can take a week. Also because these back routes mean me driving through mined areas we charge the migrants twice as much."

The young trafficker says bandits and armed groups are other dangers which justify the higher charges.

Not short of customers

He tells me that he had given up this risky business after the EU funded offers to smugglers like him a variety of inducements to quit. These ranged from giving them motorbikes, fridges or livestock to help in starting a new trade.

But, he says, he has never received a thing.

"If they give us money then we definitely will stop.

"For two years they've been promising to give it to us, but we haven't received anything yet. That's why we have to go back to this work, we can't stay penniless."

An association set up in Agadez to represent some of the region's 6,000 former people traffickers claims only a small fraction of them have received anything.

Many, like Ibrahim, are said to be returning to their dangerous trade.

It seems they will not be short of customers.

On my first evening in Agadez a convoy of pick-up trucks packed full of migrants sped past me on the desert going north.

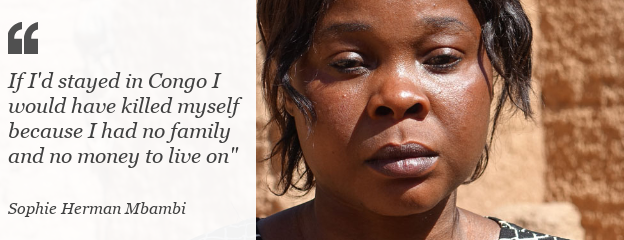

Others, like Sophie Herman Mbambi from Congo-Brazzaville, wait to join them soon. Convinced she has nothing left to lose she is undeterred by the terrible risks ahead.

"If I'd stayed in Congo I would have killed myself because I had no family and no money to live on.

"So even if I'm going to die, I'd rather my corpse was somewhere else than in my own country."

- Published13 June 2018

- Published11 September 2018