EU's Mediterranean migrant crisis: Just a mess or cynical politics?

- Published

Although the NGO rescue ship Aquarius was barred from Italian ports, coastguard ship Diciotti brought more than 900 migrants to Sicily on Wednesday

How easy it would be to bash out a righteous-sounding blog, slamming Italy's "far-right, anti-immigration, populist" deputy prime minister for bringing Europe's migration policy to its knees by cynically closing Italy's ports to the migrant rescue ship, Aquarius.

But, like most easy-sounding explanations for complex situations, the description above is facile; the truth far more grey than black-and-white.

Firstly, Europe's migration regulations have long been unfit for purpose.

Think back to the height of the migrant crisis three years ago, when EU countries couldn't slam the door on their neighbours fast enough in order to avoid the influx of asylum seekers.

And European solidarity hasn't progressed much since.

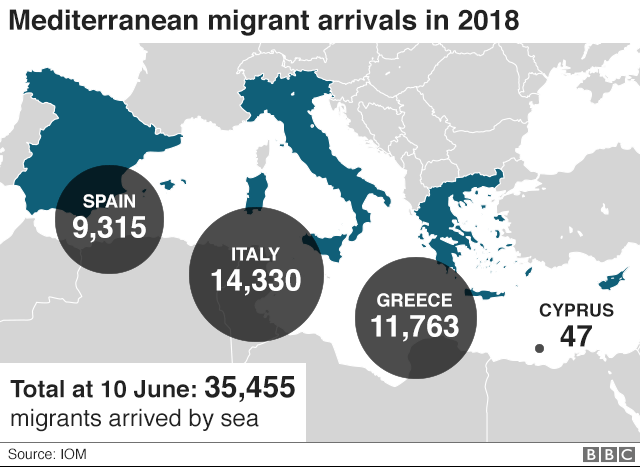

The number of migrant arrivals is down on previous years - especially for Greece, now that there is a questionable agreement in place with Turkey to crack down on people smugglers, who largely focused on Syrians trying to escape their bloody conflict.

But mass irregular migration to Europe is far from over.

Italy has continued to receive boatloads of people for years, ever since its neighbour across the Mediterranean, Libya, was thrown into lawlessness following Muammar Gaddafi's demise in the wake of the British- and French-led Nato military intervention.

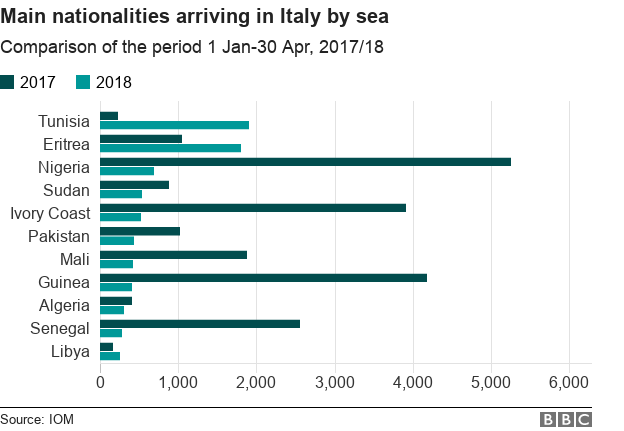

Since then hundreds of thousands of people have arrived in Italy, the majority from African countries not at war.

Under normal circumstances, most would be classed as economic migrants rather than refugees and eligible therefore for deportation, but the asylum process is lengthy and the terrible treatment suffered by migrants at the hands of Libyan gangs en route renders many cases more complex.

Italy has overflowing migrant centres and those who manage to slip away from them have sought refuge in abandoned houses.

Why Italy's Salvini has changed Europe's debate

Many migrants don't want to be in Italy at all.

Their goal is the richer north of Europe but France and Austria have blocked their path by keeping their borders with Italy firmly shut. While elsewhere along the Mediterranean coastline, France, Spain and Malta have purposefully looked the other way.

That, claims Italy's powerful new interior minister, is how his country has ended up as the "refugee camp of Europe".

And before you dismiss Matteo Salvini as an alt-right, anti-EU troublemaker and admirer-in-chief of President Donald Trump's brash and brutal style of politics (all allegations with quite some truth to them) consider this:

It was the centre-left government of normally mild-mannered former Italian Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni that first threatened to close Italy's ports to migrant rescue vessels not licensed by the Italian authorities.

Mr Gentiloni implored other EU countries to open their doors, to share some of the burden of housing and processing irregular migrant arrivals, integrating migrants with successful asylum claims and arranging the return home of those not eligible to stay in Europe.

No-one listened then. But they're certainly paying attention now.

European leaders scoring points on migration

Mr Salvini's social media crowing of "Victory!" as a result may be crass but his popularity at home, the huge success of his "Italians First!" slogan is far from a bolt from the blue.

You saw this week the reaction of many Italian mayors wanting to help the migrants on board the Aquarius despite their government's antics.

Most Italians don't want to turn their back on the destitute but their frustration has reached breaking point at being "abandoned by the EU" as they see it, to deal with what is in fact a pan-European problem.

On a visit to Sicily, Matteo Salvini said Italy must increase its deportations of migrants

Matteo Salvini is a canny politician. A populist in the true sense of the word. He is always out and about in town squares and village festivals, listening carefully to Italians' concerns.

"He knows that to get crowds of voters on your side, you need to identify a common enemy," Nicoletta Maggi told me. She's a political assistant who has known Mr Salvini since he was a teenager, when he was studying politics on paper and observing rallies in the street.

"Salvini has changed the identity of this enemy over the years, as he moved from regional to national politics. Right now he's identified immigration and the EU as the winning focus. He knows how fed-up and angry Italians are."

Italy's interior minister is far from the only European government figure scrambling to make political capital out of this latest chapter in the migrant crisis.

Spain's new prime minister rushed to earn his stripes in Brussels by stepping into the painful stand-off between Italy and Malta over the Aquarius this week with a decision to open up the port at Valencia to the migrants instead.

I expect Pedro Sánchez to want to cash in those political points at some later stage.

But Spain cuts a lonely figure in a sea of EU countries besieged by anti-immigration sentiment:

As Sweden heads towards a general election, the opposition Sweden Democrats are surging in the polls on an anti-immigration ticket

The Brexit vote had a big anti-immigration/control of national borders element to it

France's President Macron, acutely aware of the pull of the anti-immigration National Front before his election, has passed some eyebrow-raisingly tough immigration legislation. He has also kept his country's borders resolutely closed to irregular migration flows

EU's struggle for united policy

The bottom line, as Italy knows too well, is that there is a screaming absence in EU policy when it comes to a coherent, united and functioning plan to deal with irregular migration in the short and medium term.

There is the underfunded and much derided long-term EU strategy for Africa - aimed at making life better over there so fewer people are tempted to make the risky journey over here.

But as millions poured over EU borders back in 2015, the action that truly stemmed the flow was arguably nothing co-ordinated in Brussels, not even the shaky deal with Turkey.

What really made the difference was a unilateral decision by Austria's audacious foreign minister Sebastian Kurz - now prime minister - to orchestrate the closure of the migrants' route through Europe to their target countries in the richer north.

Fast forward three years and - once again without Brussels and outside the EU framework - the interior ministers of Austria (the country that currently holds the rotating EU presidency), Germany and Italy have announced they're forming their own "axis" of co-operation on security and migration.

Meanwhile the Austrian and Danish prime ministers have been discussing their preferred plan to set up camps for processing asylum seekers outside the EU.

The idea of external processing camps is not new of course. President Macron has spoken in favour of them in the past.

Similar models, much criticised by NGOs and human rights campaigners, are employed by the US and Australia.

Has the EU given Italy the nod on migrants?

But as a result of Italy's antics this week, European leaders are being spurred into action, or are at least considering it far more seriously.

As a decision-making bloc, the EU is famous for only ever making dramatic moves when proverbial backs are well and truly against the wall.

That, for example, is why EU leaders, despite all their promises and handwringing during the height of the euro crisis are now - with the currency currently in a much happier state - dragging their feet over reforms.

And so it is with irregular migration.

EU leaders were happy to forget the crisis post the 2015 flood, leaving the frontline Mediterranean countries to mop up the rest of the mess.

Call me cynical if you will, but I've noticed a fair few politically expedient elements colliding this week.

The current European Commission team, headed by Jean-Claude Juncker, is coming to the end of its mandate and considering its legacy.

The migrant crisis has made a mockery of EU unity these past years and fuelled the popularity of anti-EU, nationalist sentiment in many corners of the continent, not least in Italy - a founding EU country and not long ago one of the bloc's most enthusiastic members.

Migrants are rescued by staff members of the Aquarius

I'm reminded of a conversation I had with a high-level European contact the night before Italy's new populist government was formed.

He told me Brussels was preparing to work with the Eurosceptic politicians, helping them with issues like migration, he said, as long as they refrained from confronting EU institutions by messing with eurozone regulations, as they had previously threatened.

Watching this week's posturing by the Italian government, using the lives of migrants as political footballs yet escaping censure from the powers that be in Brussels, I'm wondering if they received a nod, however imperceptible, to take this action.

In order perhaps to alert the rest of Europe to the crisis - for the ostriches to take their heads out of the sand, as Spain's prime minister has put it - and finally co-ordinate coherent, responsibility-taking pan-European migration policies.

That would suit Brussels as well as Italy, would it not?

It would suit EU-linchpin Germany too.

Angela Merkel has been at loggerheads with her tough-on-migration interior minister, Horst Seehofer, this week. She more than most EU leaders has been politically burnt by Europe's asymmetrical attitudes to irregular migration.

After the Aquarius debacle, migration is assured a front-and-centre spot at a summit of EU leaders at the end of this month.

If, even now, no common European solution is found, Angela Merkel has warned, the foundation of the European Union will be called into question.

- Published11 June 2018