African women on the shame of hair loss

- Published

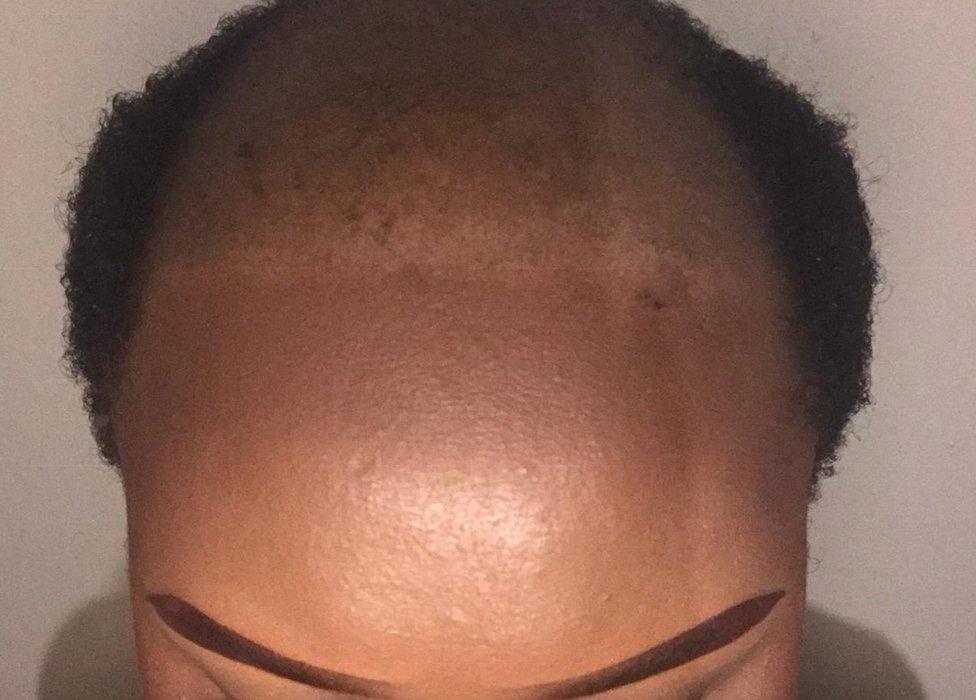

Bandile says giving her hair a break could have prevented her baldness

Years of styling, braiding, pulling, relaxing and sewing in weaves have left a 31-year-old aspiring South African model with a balding head.

"Every time I took out my weave at the salon, I would have them chemically 'relax' my hair and would then put on another weave on the same day - I was never with my own hair," says Bandile (not her real name).

It is a form of hair loss called traction alopecia, and she was in secondary school when she first noticed her hair was falling out.

But the Johannesburg resident is not alone - the condition affects one-third of women of African descent, according to a study in the medical journal Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology.

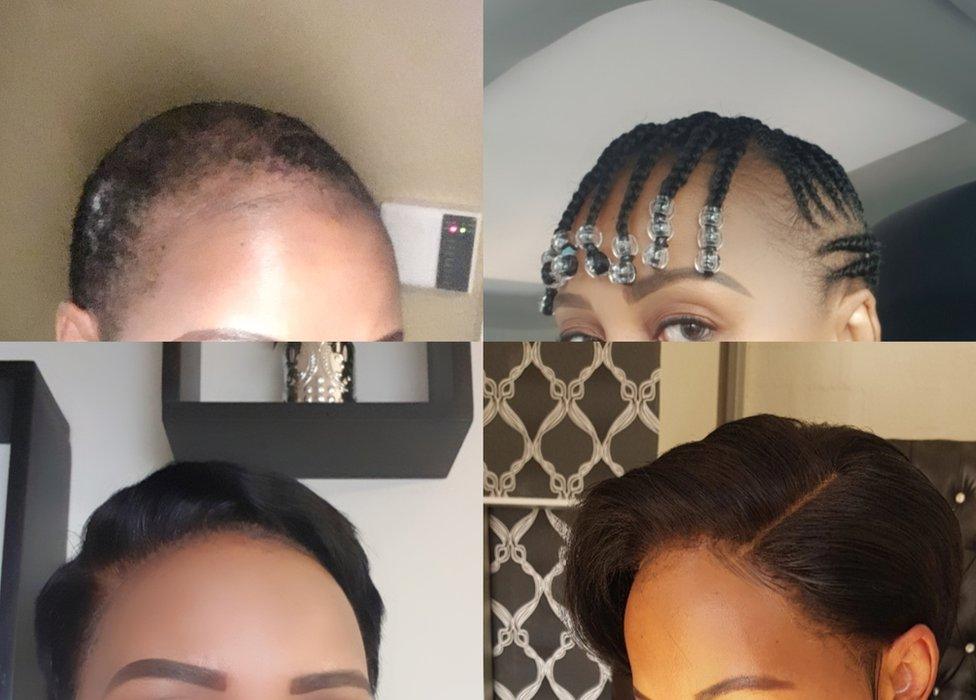

Women of African descent are advised to rethink their hairstyling to avoid hair loss

A study three years ago of almost 6,000 women of African descent by Boston University's Slone Epidemiology Center found that almost 48% of respondents had suffered hair loss on the crown or the top of the head - mostly caused by traction alopecia.

Given the topic tends to be shrouded in silence, the true figure may be higher.

"If we all had to take off our wigs at work, eight out of 10 women would have hair issues. It's just something we don't and won't talk about. We are very ashamed of it," says Bandile.

"The doctor told me I'd pulled my hair from the root when I used glue to weave it. That glue wasn't removed and it damaged the follicle root of my hair."

'Misconceptions about natural hair'

Bandile blames the problem on the widespread belief that braids and plaits promote hair growth.

"The misconceptions we grew up with was that a weave is more manageable than your natural hair."

And some estimates suggest women across Africa spend an estimated $6bn (£4bn) on weaves, braids and wigs each year.

"Every woman feels more sophisticated with a weave. Half of us feel like when you've got a long weave and long hair, you look a bit more beautiful and you're accepted better in society," she says.

"Every black woman I know is obsessed with growing their hair long. They put thin plaits on the hairline, which pulls it."

Most of the women are using the wrong glue for their weaves or maybe they leave their braids or weaves in for extended periods of time"

It is a story that Susan Magai, who owns a beauty salon in Tanzania's main city Dar es Salaam, is all too familiar with.

"Most of the women are using the wrong glue for their weaves or maybe they leave their braids or weaves in for extended periods of time," she says.

"We advise our clients to leave weaves in for two weeks but some leave them in for three months and start to lose their hair."

More on the politics of hair and its care:

Ms Magai's salon offers a steam treatment she says opens up the pores on the head to allow the hair to grow.

"The steaming is like baking the hair. We use coconut oil and apply it on to the scalp. Then we cover the hair and bake it using a machine," she says, adding that it can take several months before the effects are visible.

According to the Institute of Trichologists in the UK, steaming can be good for African hair because it adds moisture, which makes it more pliable and less prone to breakage. However, the association warns that steaming alone cannot stimulate growth after hair loss.

Going bald after child birth

Bandile tried a peppermint remedy to open up her scalp pores and after that failed, minoxidil - a blood pressure drug - which causes hair growth as a side-effect.

"The hair was re-growing but it was becoming expensive so I left it," says the model who plans to see a trichologist in June about a possible hair transplant.

The hair industry in Africa is a multi-million dollar business

UK-based doctor Jumoke Koso-Thomas, who contributes to a blog focused on black women's health, says that while hairstyling contributes to the majority of alopecia cases, for some there is also a genetic component.

For example, hair loss can be a symptom of problems with the thyroid gland or iron deficiency, she says.

"Childbirth, being on the pill and stress can also make women lose their hair," Dr Koso-Thomas adds, though such hair loss can be temporary.

Boitumelo Monyaki, a 39-year-old financial management student from Johannesburg, went completely bald eight years ago - something she believes was linked to the birth of her first child in 2002.

Boitumelo Monyaki says that her hair is growing again but is still thin

"I've learnt that plenty of women in my family lose their hair after giving birth," she says.

It has been happening since my great-grandmother's time."

Ms Monyaki says losing her hair affected her confidence but she has learned to accept that her hair may never grow back to its previous fullness.

She wants to see more help available for African women dealing with hair loss: "Even salon owners and stylists don't know how to treat this problem."

'Embracing their Africanness'

Dr Koso-Thomas advises that a healthy balanced diet containing vitamin C, vitamin B and selenium, found in fresh fruit and vegetables, helps to nourish the hair root and can help combat traction alopecia - and avoiding stress can prevent hair loss too.

A vitamin-rich diet helps to promote healthy hair growth

Crucially, she believes girls and younger women need to reassess the way they style their hair.

"We need to be telling them: 'Try not to do too much to your hair. Don't put too many chemicals, don't continually braid your hair. Let it rest, give it time to recover and do different styles at different times.'"

Bandile says it is advice that may gain ground as more women are going for the "natural" look.

"They like their natural hair and are embracing their Africanness," she says, admitting that she is tired of "always hiding under wigs".

"I want to just be able to go to work with a full head of natural hair."

- Published21 July 2015

- Published5 October 2018

- Published27 June 2018