The woman bringing Mandarin to Uganda

- Published

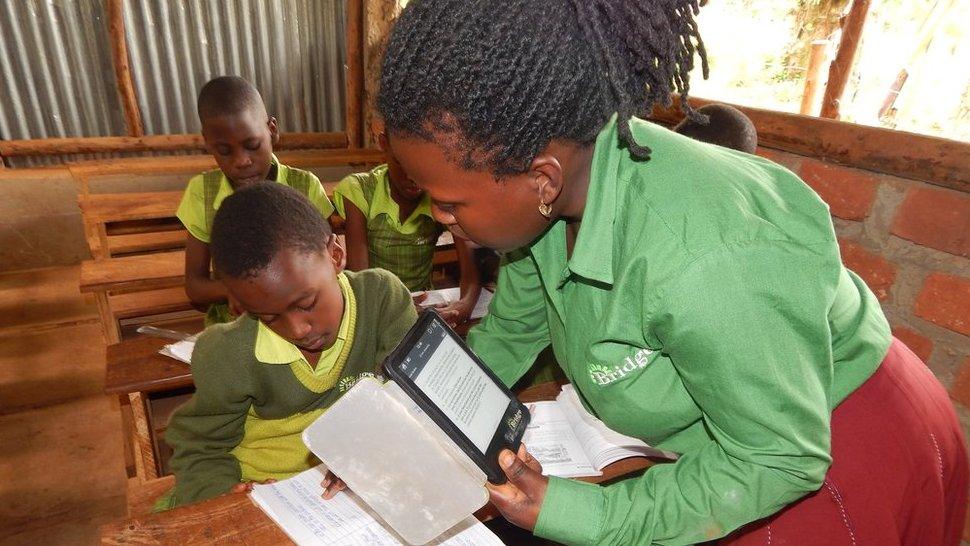

Wang Li Hong Sooma in a class in Kampala, Uganda

Wang Li Hong Sooma, who moved to East Africa from China more than two decades ago, is determined to teach Ugandans how to speak Mandarin.

She and her Ugandan husband, Ayub Sooma, are organising nine-month intensive courses for secondary school teachers to learn China's dominant language.

The first 30 teachers have now completed their training and have started holding Mandarin classes in schools across the country.

The couple, who own their own secondary school on the outskirts of the capital, Kampala, can be seen as the perfect symbol of blossoming China-Uganda relations.

Together they can chat in a mixture of English, Mandarin and some of the local language Luganda.

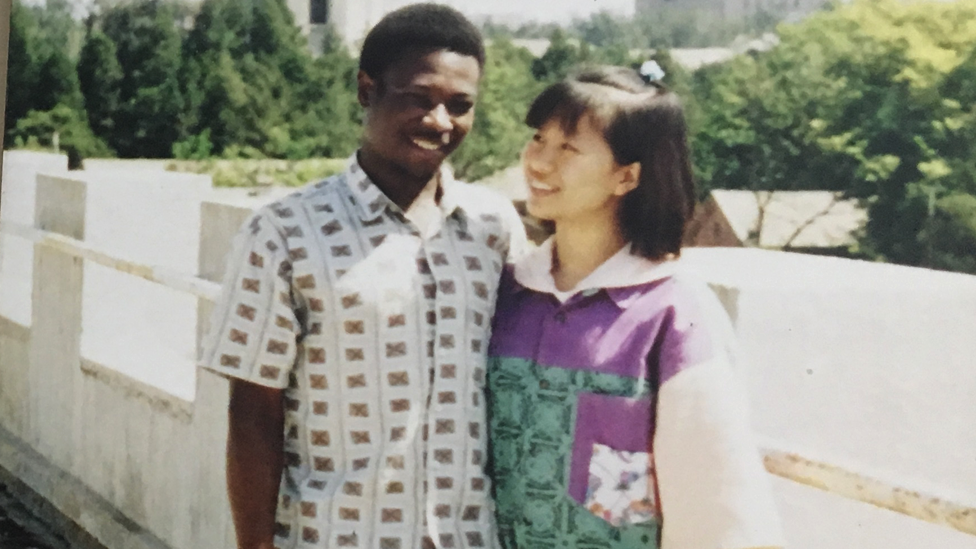

Wang Li Hong Sooma (R) and Ayub Sooma (L) faced opposition at first to their union

They met 26 years ago in Beijing, when Mr Sooma was studying at Tsinghua University.

Though at first, Mrs Wang says, it was not easy for them to be together.

"It was a war! At that time, they thought I was a very loose girl to date a black boy. But I knew he is very honest and has a good heart to help other people."

They now have three children and Uganda has been their home since 1996.

New frontier

In that time, the economic relationship between China and Uganda has grown tremendously and the couple are in a perfect position to capitalise on that.

How easy is it to learn Mandarin?

There is no alphabet, just thousands of characters. There are so many that no-one can give a definitive total, but it is believed to be around 60,000

It uses a tonal system - four-and-a-half tones are used, meaning a single word can have many meanings

"Ma" can mean mother, horse, hemp, or a reproach

Tone one - A fairly high, even tone

Tone two - A rising tone, much like the sound at the end of a sentence with a question mark

Tone three - Falls then rises. Like the second, but must dip first

Tone four - Sharp falling tone, a little like how the end of a sentence with an exclamation mark sounds

Half tone - Pronounce words with light tones in about half the time you would a normal word, without putting emphasis on it

They want to turn their school into a new frontier for Mandarin and Chinese culture.

Their teacher-training programme is being paid for by the government in Beijing - though it is not clear how much is being stumped up for the initiative.

Another 40 secondary school teachers have signed up to learn Mandarin

"They are funding these Chinese teachers [from China], their salary and their accommodation. They also help the trainees - providing their food, their accommodation and some allowance," says Mrs Wang.

Most Mandarin lessons in Africa are taught through Chinese government-run Confucius Institutes.

The first opened in Kenya in 2005 and there are now nearly 60 across the continent.

Some schools in Zambia and Tanzania also offer the subject, and the scheme in Uganda is sub-contracted to Mrs Wang by the Confucius Institute.

You may also be interested in:

Forty more teachers are now enrolled and classes start at 08:00 and finish at 22:00 from Monday to Friday.

To become fluent and be able to teach a language within nine months is a huge undertaking, though Pavin Mulokwa, a teacher from the western district of Mbarara, sees it as an opportunity to broaden her job prospects.

Another trainee, Praise Twebaze, agrees and hopes it will enable him to travel too.

"We can go beyond lands where they use English but as well to lands where they use Chinese," he says.

For 13-year-old Denis Mulungi, the Mandarin lessons he has just started at Lubiri Secondary School in central Kampala could shape his future career.

"Learning Chinese, it can help me get good jobs in future. Learning Chinese can help me go abroad. It could be easy for me to communicate with other people who know Chinese, if I go to China."

Chinese imperialism?

It is not just the Ugandans who see this course as a life-changing opportunity.

Gao Ya Hui, who has been teaching Mandarin in Uganda for a year, says it has changed her perceptions of Africa.

When I came here it changed my stereotypes about African people"

From Xian city in central China, the 39-year-old left her husband and child behind to come and teach but was warned by family and friends not to because of "diseases and war".

"When I came here, it changed my stereotypes about African people. When I go back to China, I will introduce the real Africa to the people in China and change their way of looking at Africa."

But some, like Fred Muhumuza - a Ugandan economist who has followed the growth of trade between China and Uganda - says questions have been raised about China's motives for funding such a scheme and whether the initiative has been forced on the Ugandan government.

He lists some the concerns he has heard: "Is this Chinese imperialism? Taking over Africa's resources, taking over even Africa's cultures and languages and wiping out everybody else?"

Narrowing the trade gap

Aggrey David Kibenge, Uganda's education ministry spokesman, dismissed such apprehension, saying it was not political and that it was not unusual for a foreign government or organisation to support the teaching of a particular language.

Lubiri Secondary School in Kampala is already holding Mandarin classes

Supporters of Mandarin lessons point to the benefits for Uganda from economics and trade: Giving young Ugandans a better chance at competing on the global stage and an opportunity to narrow a massive trade gap.

According to the World Bank data, Uganda's imports from China were $622m (£474m) in 2013 and rose to $985m in 2017.

These are mainly consumer goods, machinery, electronics and textiles.

However, exports of Ugandan products to China reduced over the same period from $71.9m in 2013 to $33.4m in 2017.

Mrs Wang's goal is to have 100 teachers trained up and teaching Mandarin in 50 Ugandan schools - both those that are privately and government run - by 2021.

She sees it as a win-win situation, giving the example of how Chinese students have benefited from learning English in their understanding of America.

"We learnt their language, we understand them. We learnt their language, we learnt their technology. We learnt their skills and then we developed."

- Published16 November 2016

- Published4 December 2015

- Published5 December 2015

- Published26 October 2016

- Published26 April 2023