Mali attack: Behind the Dogon-Fulani violence in Mopti

- Published

The Dogon people have lived in central Mali for centuries

The slaughter on Saturday of more than 130 Fulani herdsmen in central Mali, allegedly by members of the Dogon ethnic group, is the latest and most deadly incident in an increasingly violent conflict.

In 2018, 202 civilians were killed in communal violence in 42 incidents in Mali's Mopti region, external, according to New York-based group Human Rights Watch.

While there have been conflicts between the more settled Dogon people and the Fulani herders in central Mali for a long time, they have become increasingly violent since a militant Islamist uprising in the north of the country in 2012.

The government appeared to blame the Dogon self-defence group, Dan Na Ambassagou, for Saturday's attack and has outlawed it, even though the group has denied any involvement.

Who are the Dogon?

The Dogon people, who largely practise settled agriculture, have lived in the Bandiagara escarpment in central Mali for centuries.

Homes carved into the limestone rock and the architecture, as well as the traditional way of life, led to the escarpment being declared a World Heritage Site 30 years ago.

The region had been attracting a growing number of tourists until the uprising began in the north in 2012.

Who are the Fulani?

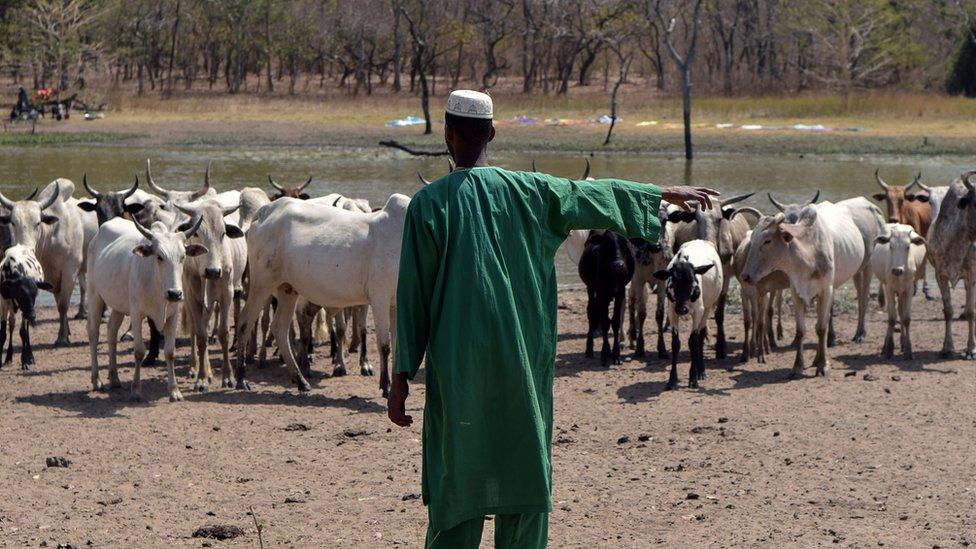

The Fulani, known in Mali as the Peulh, are a largely Muslim ethnic group of semi-nomadic herders.

Numbering at least 38 million, they are spread across West Africa, from Senegal in the west to the Central African Republic.

Some have settled in cities but those who continue to herd cattle can range across vast distances and have at times come into conflict with agricultural communities.

In Nigeria, there has also been a similar cycle of violence between Fulanis and settled farmers, which in 2014 was said to have been the fourth most deadly conflict in the world.

What is behind this conflict?

Dogon people have often accused the Fulani of bringing their cattle onto their farms and destroying their crops.

This has historically led to tension and at times violence between the groups, but competition over resources was frequently resolved by negotiation.

But the militant Islamist conflict that began in northern Mali in 2012 and spread to central areas by 2015 brought more instability, weapons and a lack of government control into the region.

The Dogon, who have been victims of militant attacks, accuse the Fulani of aiding the jihadists. Meanwhile, the Fulani say that the Dogon self-defence groups have been armed by the government, and are carrying out atrocities against them, which is denied by the authorities.

Since 2015, government control in Mopti has weakened, meaning that people do not feel they can rely on the authorities, the BBC's Alou Diawara reports from the capital, Bamako.

What is the Dan Na Ambassagou?

Dan Na Ambassagou, which means "hunters who trust in God" in the Dogon language, is an association that was formed from local self-defence groups.

It was created in 2016 to "defend our community", according to members quoted by Human Rights Watch, but came to prominence last year.

There have been accusations that it has been involved in a number of the attacks on Fulanis last year, but it has denied this.

More than 130 people were killed in Saturday's attack on the villages of Ogossagou and Welingara

Likewise, it was accused of being behind Saturday's attack as the perpetrators were dressed in traditional Dogon hunting gear. But Dan Na Ambassagou says the association was not involved.

"We have nothing to do with this massacre which we utterly condemn," it said in a statement.

"Anyone can wear hunters' costumes, they are available in the markets."

Are there Fulani self-defence groups?

Some community members formed the Alliance for the Salvation of the Sahel (ASS) in May last year to protect Fulanis from armed groups in Mali and Burkina Faso, Human Rights Watch says.

But it is not clear what links the ASS has with other Fulani village self-defence groups.

The ASS is accused by Dogon militia of being linked to militant Islamist groups in the area, but it denies this.

What are the authorities doing?

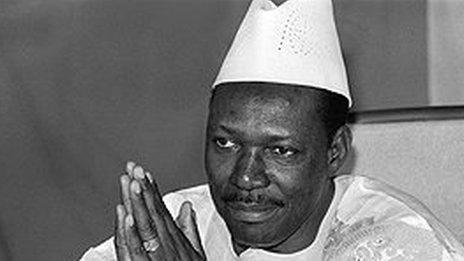

In addition to banning Dan Na Ambassagou, President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita also sacked two generals: chief of staff Gen M'Bemba Moussa Keita and chief of land forces Gen Abdoulaye Coulibaly.

In a statement, the presidency said that "the protection of the population remains and will remain solely in the hands of the state", distancing itself from claims that it has outsourced the fight against the jihadists.

"Our forces will... actively disarm any person who should not be armed," it added.

International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor Fatou Bensouda condemned the attack. She said it could fall under her jurisdiction and that her office "will take all necessary steps to ensure the investigation and prosecution of those who participated in or otherwise contributed to what appears to be egregious crimes".

The ICC has been working with the Malian authorities since 2012 on the impact of the jihadist uprising.

- Published26 August 2020