Letter from Africa: 'We're not cleaners' - sexism amid Sudan protests

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, Zeinab Mohammed Salih considers why female protesters are angry with their male counterparts.

The anti-government protests in Sudan are unwavering despite a state of emergency imposed in February.

This is largely thanks to the efforts of the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), which has been organising the demonstrations against President Omar al-Bashir's nearly 30-year rule.

The body represents health workers, lawyers and teachers, amongst others - though some would argue, not women - even though it is estimated that more than 70% of the protesters who have been out on the streets since December are female.

The SPA got itself into hot water when it suggested that instead of a day of scheduled protests on Saturday 9 March, people come out instead to clean the streets.

The streets of the capital, Khartoum, are particularly mucky - and it was felt that a good tidy up would restore a sense of pride in the city.

Since the protests began, the SPA has been particularly praised for the beautiful language used in its statements calling for action.

However, in this instance it struck the wrong tone - urging women in particular to come out for the task because they "cared more about cleaning".

The street-cleaning faux pas began as anger about the sexist attitudes of male protesters and has mushroomed into anger about how women are treated in Sudanese society"

The message was met with outrage by many female protesters - and sparked a debate on social media about the sexism of the uprising.

A day later, the SPA, which has female spokesperson, issued a contrite apology.

These protests began in reaction to a hike in bread prices - and then mushroomed into the most serious challenge to Mr Bashir's hold on power since an Islamist-backed coup in 1989.

'We are not queens'

Likewise, the street-cleaning faux pas began as anger about the sexist attitudes of male protesters and has mushroomed into anger about how women are treated in Sudanese society.

On social media, comments such as "even women have protested" have been a particular point of contention.

Protesting women are not a new phenomenon in Sudan. In 1946, 10 years before independence, the country's first female doctor, Khalida Zahir, took to the streets against British rule and was arrested and flogged.

Schoolgirls have also taken to the street in the anti-government protests

Another sore point is the recent use of the word "Kandaka" to describe a female protester.

Kandaka was the word used to refers to queens in the ancient Kush kingdom that ruled Sudan thousands of years ago.

The literal translation from Arabic of the controversial SPA statement read: "When is the cleaning day? On Saturday Kandaka - yes we mean you, because you care more about it."

The dislike for the term hinges on the fact that female protesters don't see themselves as above others - they are the people, taking the same risks as everyone else.

The irony of the word also angers others as they say there is no gender equality in the mainly Muslim country where female genital mutilation is still practised - almost 90% of Sudanese women have been cut.

You may also be interested in:

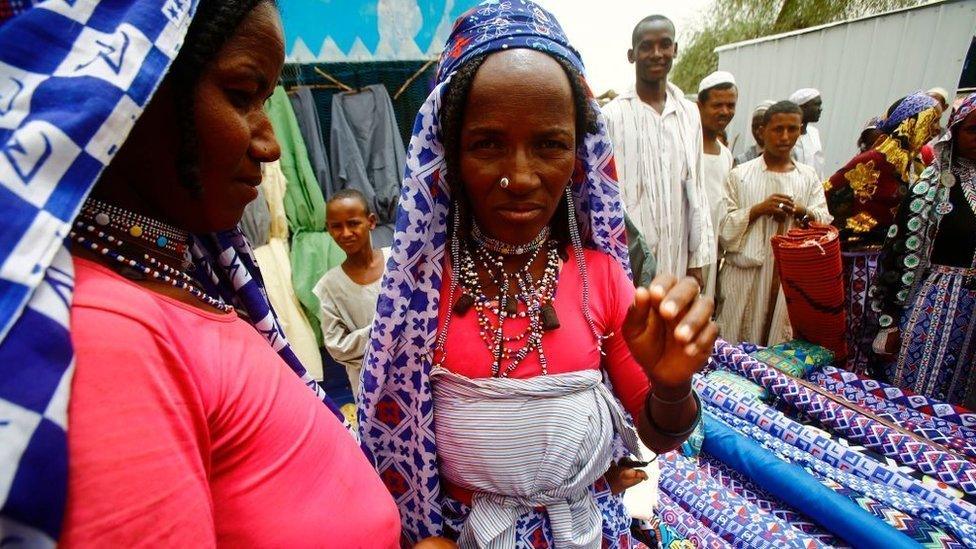

Women from all backgrounds and ages have been protesting - some on the frontline, others standing in front of their houses sheltering those who flee live ammunition or tear gas.

They have also been serving protesters with food and drinks.

'The time has come'

Images have also been circulating on social media of prominent men who support the government and have criticised the demonstrations, mocking them by feminising their faces on Photoshop. The implication is that they are cowards.

This has led a group of feminists to launch a campaign called "Waqto wa naso", meaning "The time has come", calling for such sexist attitudes to be denounced.

According to the No To Women Oppression group, between 40,000 and 50,000 women are arrested and flogged each year by the police for flouting the country's Public Order Act introduced by Mr Bashir's government.

The law regulates what women can wear - they can, for example, be flogged for wearing clothes such as trousers that are considered indecent or simply for being out with men who are not their relatives.

Sudan's Public Order laws

Article 152 of the Criminal Code applies to "indecent acts" in public

This can include wearing an "obscene outfit" or "causing an annoyance to public feelings"

Women must wear a headscarf and cannot wear trousers

Between 40,000 and 50,000 women are arrested and flogged every year by public order police because of their clothing

Women have also been charged under this law for being alone with a man

People can also be charged for drinking alcohol under these laws

Interestingly, earlier this month a court overturned flogging sentences for nine women accused of taking part in protests.

And the clean-up day in Khartoum did take place - with both men and women taking part.

These could perhaps be seen as signs of changing times for women in Sudan.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published25 February 2019

- Published14 August 2019

- Published11 July 2018

- Published13 September 2023