Will Facebook's digital money Libra be good for Africa?

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, technology writer Andile Masuku looks at what the launch of Facebook's digital money could mean for Africa.

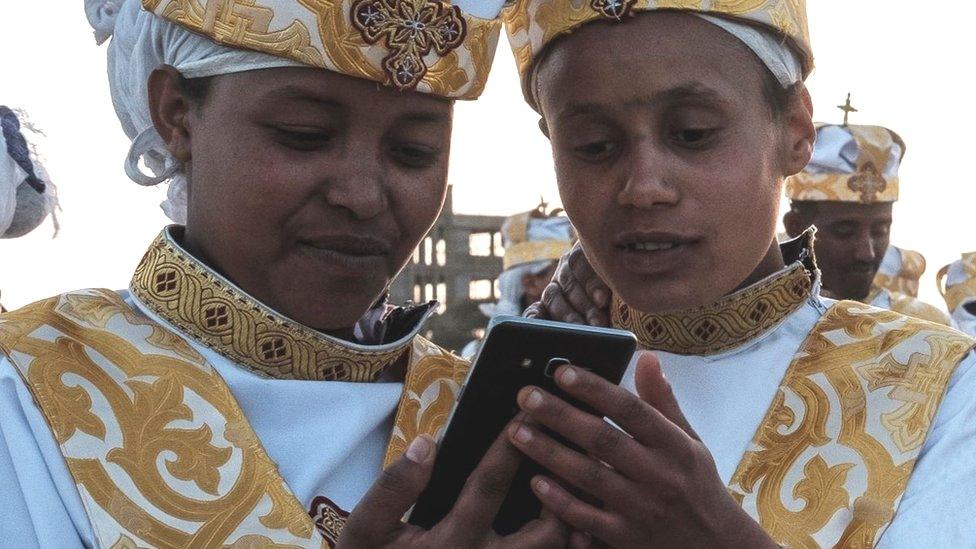

From early next year, Facebook intends to let its two billion-odd users - more than 139 million of whom are in Africa - make digital payments through its apps and popular messaging service WhatsApp using a new crypto-currency called Libra.

It could have profound implications for a continent which receives a huge amount of remittances - and is one of the least-banked regions of the world, something that has allowed for other innovations like mobile cash payments to take hold in Africa.

I relish the prospect of a network like Libra permanently disrupting the lucrative cash remittance businesses of large banks and money transfer services"

As a Zimbabwean living in South Africa, I have become numb to the daylight robbery that ensues whenever I receive money from abroad or send cash to my family back home.

As such, like many other cautious pragmatists, I relish the prospect of a network like Libra permanently disrupting the lucrative cash remittance businesses of large banks and money transfer services like Western Union and MoneyGram.

According to a World Bank report published last year, the cost of sending cash in sub-Saharan Africa was at least 20% higher than any other region in the world. The report revealed that sending $200 to and from the region in the first quarter of 2018 cost a whopping $19.

But we must not be naive to the myriad factors responsible for maintaining market inefficiencies and actively engineering economic complexities which corporations like Western Union exploit to great effect.

The cost of sending cash in sub-Saharan Africa is 20% higher than any other region in the world

The fact is, many governments in Africa have enabled the remittance industry status quo and have come to rely on lining their coffers with remittance-related revenue.

Security risks

African governments are also deeply suspicious of crypto-currencies, like Bitcoin. The long list of countries which have, in some way or another, prohibited the use of crypto-currencies includes Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia and even my native Zimbabwe, which is well on its way to being a cashless society thanks to the growing adoption of mobile money services.

It abandoned its own currency for 10 years because of hyperinflation, and it is currently in the throes of trying to reassure a sceptical nation that the newly introduced Zimbabwean dollar has value.

Policy makers in Zimbabwe have argued that the idealised notion of a crypto-currency does not adequately take into account some of the very real limitations and security risks.

Think challenges in levying taxes, the risk of unwittingly enabling illicit activity and money-laundering, and of course the potential susceptibility to crypto-hackers.

Behind the jargon

What is a crypto-currency?: It is has no notes or coins, exists online, and uses a technology called blockchain to underpin it. The most well-known one, Bitcoin, is not issued by governments or traditional banks

What is blockchain? It is a method of recording data, a digital ledger of transactions distributed across computers around the world beyond the control of one person or entity

What makes Libra different from Bitcoin? It will use blockchain technology but the digital ledger will be managed by a group of known companies

And these are things that African leaders need to address with Facebook up front. In the US, lawmakers have already proposed a moratorium on the Libra rollout until Facebook assures Congress that Libra will not exacerbate money-laundering and the funding of terror groups among other issues.

Facebook's Libra white paper, which outlines the tech giant's plans to re-imagine global finance, does show that unlike completely decentralised digital currencies such as Bitcoin, which operate outside the oversight of central authorities or banks, Libra is set to be backed by a reserve of actual currencies and assets.

Facebook is using this difference to convince policy-makers that Libra is a bankable bet. It has the high-powered backing of the likes of Visa, MasterCard, Uber, Spotify and even South Africa's PayU.

'Free internet' backlash

As Facebook representatives push back against concerns regarding the extent of the company's self-interest in the Libra project, we would do well not to forget how it formerly served the world poverty-porn laden rhetoric to justify the global roll-out of Free Basics offering several years ago.

Back then, the tech firm audaciously sold Free Basics, which lets people in some countries access Facebook and other websites without charge, as mankind's most significant development towards promoting "internet as a right" for all.

India opposed Facebook having a monopoly over the internet with Free Basics

Dubbed by detractors as the "Internet According to Facebook", many African countries lapped it up.

India, quite famously, did not, arguing that it undermined the principle of net neutrality - the idea that all internet traffic should be treated equally - and that it was improper to allow Facebook to deliver a dumbed-down version of the internet to hundreds of millions of people.

You may also be interested in:

With the help of the pan-African mobile telephone operator Airtel Africa, Facebook rolled out Free Basics in no less than 17 African countries.

It is hard to argue that offering poor, disconnected Africans limited web access to services like health, education, jobs, communication and local content at no cost to them is anything but beneficial.

Yet Facebook's now infamous business model of monetising user data makes it impossible to ignore the potential adverse long-term impact of allowing such a firm to profit from curating the only version of the internet millions of Africans may ever come to know.

Given the company's high-profile shortcomings, there is good reason to distrust Facebook and many die-hard crypto-currency proponents think of the Libra concept as the perfect prop for a hopelessly broken global finance industry.

The internet was cut off in Ethiopia recently first because of exams and then after an attempted coup

Critics also point to the ease with which African governments can cut off the internet and messaging apps, meaning if it suited them they could effectively cut off their citizens from accessing digital cash. Would it be wise for us to become too dependent on Libra?

The recent network issues on Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram experienced in South Africa this past week have also served as a sober reminder of how economically disruptive relying on Facebook's Libra could prove to be should a similar outage occur again.

I am encouraged by how key personalities within Africa's innovative digital money community are leading impressively nuanced debate about the potential pros and pitfalls of Libra.

Social media posts and impassioned blog posts by Nigeria's Seyi Taylor, who thinks if it proves cheap and convenient, uptake could be rapid, external, and Kenya's Michael Kimani, who flags how it targets the poor, have so far prompted robust discussion online, external that one can only hope will filter into the hallowed halls of policy-making across the continent.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

With that all said, if on a future Sunday I could send my folks $100 to pay for some cattle vaccines via a WhatsApp message, and they could immediately go to their local agri-mart and make a purchase using Libra - that would be rather nifty.

More Letters from Africa

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published18 June 2019