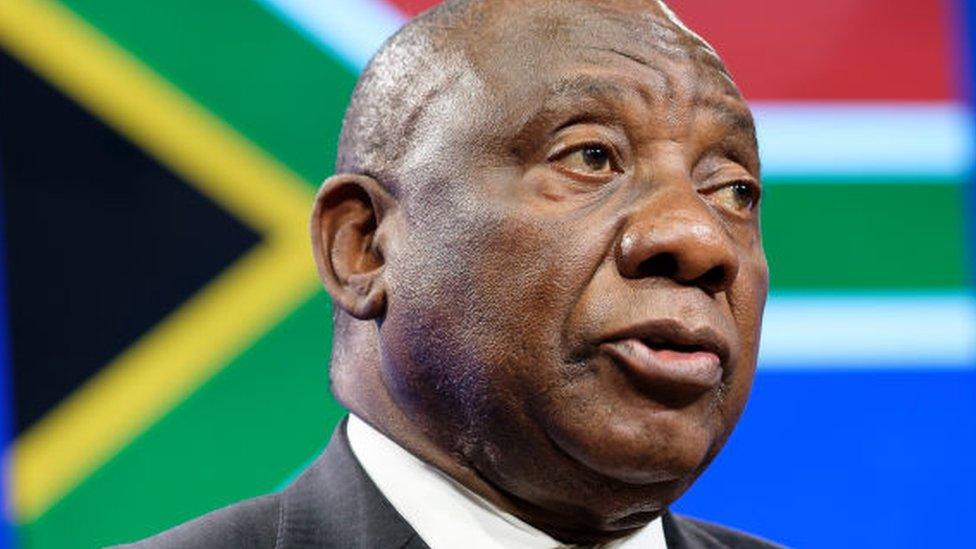

South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa accused in corruption row

- Published

South Africa's corruption watchdog says President Ramaphosa should be investigated by prosecutors

South Africa's watchdog has accused President Cyril Ramaphosa of misleading parliament and potential money laundering over a campaign donation.

Mr Ramaphosa has previously denied any wrongdoing.

His supporters say the allegations made by Public Protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane are politically motivated.

The scandal is seen as part of a larger power struggle within the governing party, reports the BBC's Andrew Harding in Johannesburg.

Last year, Mr Ramaphosa told parliament that he had not received election campaign donations from a controversial local company during his bid to lead the ruling African National Congress (ANC).

It later emerged that was not true. Mr Ramphosa apologised, and said he had been misinformed. But South Africa's corruption watchdog has now said Mr Ramaphosa deliberately misled parliament and should be investigated by prosecutors.

'Bitter power struggle'

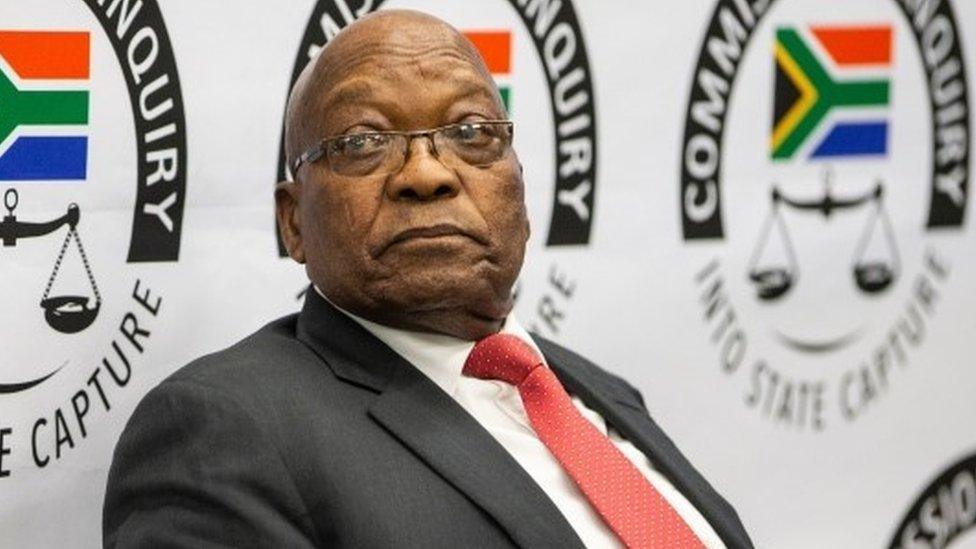

The explosive allegations against President Ramaphosa are seen by many as a power battle for control of the ANC and South Africa itself. Party factions have only become more entrenched since former President Jacob Zuma, 77, was forced to resign as president in February 2018 amid widespread allegations of corruption, which he denies.

He was replaced by his then-deputy, Cyril Ramaphosa, who promised to tackle corruption in the country. Many South Africans believe he means it. Mr Ramaphosa described Mr Zuma's nine years in office as "wasted".

Critics of Ms Mkhwebane accuse her of bias and say she has become a participant in a fight-back by allies of former President Zuma, who is now facing numerous allegations of corruption himself.

The battles are likely to play out in South Africa's courts, which have remained largely independent.

Jacob Zuma: I have been vilified

Mr Zuma is to give further testimony to an ongoing corruption inquiry, withdrawing an earlier threat to pull out. His lawyer, Muzi Sikhakhane, had said on Friday that Mr Zuma would "take no further part" in the proceedings.

But the judge overseeing the inquiry later said Mr Zuma had agreed to provide it with written statements. The inquiry is investigating allegations that the ex-leader oversaw a web of corruption while in office..

Why did Mr Zuma threaten to withdraw?

The lawyer, Mr Sikhakhane, told the inquiry commission in Johannesburg: "Our client from the beginning... has been treated as someone who was accused." He criticised the investigation led by Judge Raymond Zondo, alleging that it was a "political process where the left hand doesn't know what the right hand is doing". He also said Mr Zuma had been subjected to "relentless cross-examination".

Mr Zuma had been due to give a final day of testimony on Friday but the inquiry was adjourned. "I expected that he would co-operate," Judge Zondo said following Mr Zuma's withdrawal. "The first purpose was to give him an opportunity to tell his side of his story."

But shortly after, the judge said Mr Zuma had agreed to provide written statements and then return to the inquiry at a later date.

What is Mr Zuma accused of?

The allegations against Mr Zuma focus on his relationship with the controversial Gupta family, which has been accused of influencing cabinet appointments and winning lucrative state tenders through corruption.

He has also been accused of taking bribes from the logistics firm Bosasa, which is run by the Watson family. All the parties deny allegations of wrongdoing.

The scandal is widely referred to as "state capture" - shorthand for a form of corruption in which businesses and politicians commandeer state assets to advance their own interests.

On Monday, Mr Zuma gave a lengthy address in which he claimed the corruption allegations were a "conspiracy" aimed at removing him from the political scene. "I have been vilified, alleged to be the king of corrupt people," he said.

Supporters of Mr Zuma danced after he announced that he would no longer take part in the inquiry

He implied that the UK and US had been - and still were - part of an elaborate plot to discredit him, even as he tried to bring about political and economic change in South Africa.

Mr Zuma also said other foreign agents had tried to poison him, without naming them or offering any proof. "I never did anything with them unlawfully," he said of the Gupta family. "They just remained friends, as they were friends to everybody else."

He also objected to allegations that he had allowed the state to be "captured" by the family. "Did I auction Table Mountain? Did I auction Johannesburg?" he asked.

On Tuesday, the former president said he had received death threats following his testimony.

How did 'state capture' operate in South Africa?

Many of the revelations from the inquiry concern the relationship between two families - the Zumas, centred on the former president, and the Guptas, three Indian-born brothers who moved to South Africa after the fall of apartheid.

The two families became so closely linked that a joint term was coined for them - the "Zuptas".

Huge protests were organised to force Jacob Zuma from power

The Guptas owned a portfolio of companies that enjoyed lucrative contracts with South African government departments and state-owned conglomerates. They also employed several Zuma family members - including the president's son, Duduzane - in senior positions.

According to testimony heard at the inquiry, the Guptas went to great lengths to influence their most important client, the South African state. Public officials responsible for various state bodies say they were directly instructed by the Guptas to take decisions that would advance the brothers' business interests.

It is alleged that compliance was rewarded with money and promotion, while disobedience was punished with dismissal.

- Published16 July 2019

- Published15 July 2019

- Published15 July 2019

- Published14 February 2018

- Published9 October 2017