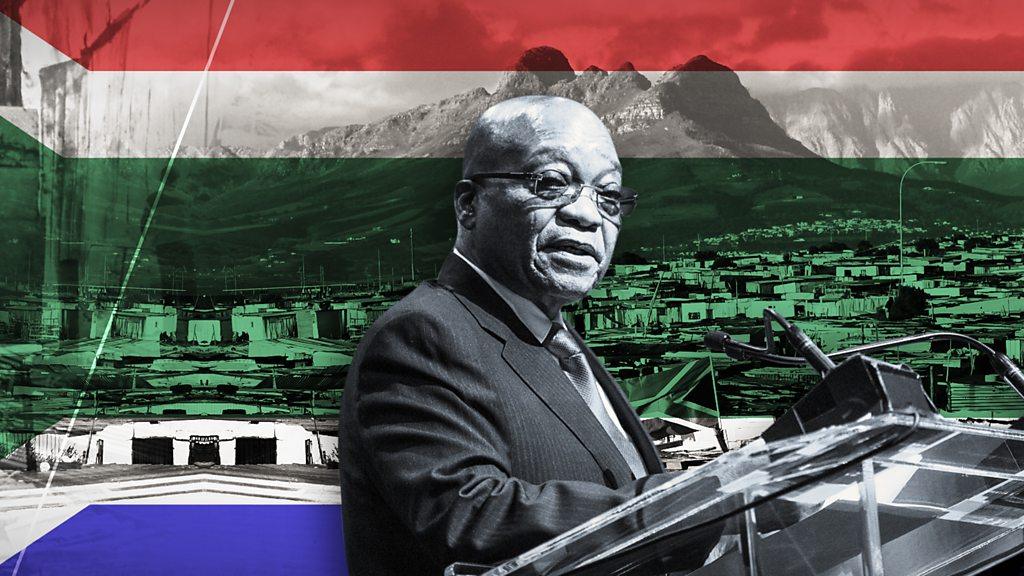

State capture: Zuma, the Guptas, and the sale of South Africa

- Published

South Africa's former President, Jacob Zuma, is giving evidence this week at a commission set up to investigate corruption allegations during his time in office.

The inquiry takes its name from an academic term, "state capture", that has become a buzzword - shorthand for the multiple scandals that plagued the Zuma administration and eventually brought it down.

So what exactly is state capture?

State capture describes a form of corruption in which businesses and politicians conspire to influence a country's decision-making process to advance their own interests. As most democracies have laws to make sure this does not happen, state capture also involves weakening those laws, and neutralising any agencies that enforce them.

Jacob Zuma says his hands are clean

"State capture is not just about biasing public policy so that it systematically favours some corporations over others," Abby Innes, assistant professor of political economy at the London School of Economics, told the BBC. "It's also about strategically weakening that part of the state's law enforcement mechanism that might crack down on corruption."

"Classic corruption involves individual politicians taking side-payments for preferential treatment in outsourcing contracts, a small deal here, a license payment there," Dr Innes said.

"Full-on state capture is where corporations can influence the nature of the legislative process, and political actors allow them to do so for private gain. The whole policy-making structure of the state becomes commodified - something that politicians are willing to sell."

If traditional corruption means slipping a bribe to every police officer that catches you speeding, state capture means paying to have your car fitted with police lights so that no officer dare stop you from speeding again. Rather than paying to get away with breaking the law, you pay to make the law work for you.

Where did the term come from?

The concept of state capture was defined in a 2003 World Bank report on corruption in eastern Europe and central Asia.

Joel Hellman, a report co-author who now serves as dean of the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, said a new term was needed to describe the extraordinary tactics that certain firms, owned by oligarchs, were using to maintain their dominance of the market.

"We noticed that these firms were active players not just in lobbying, which goes on everywhere, but also in using private payments to public officials to shape the laws of institutions in their favour," Mr Hellman told the BBC.

State capture theory initially helped explain the oligarchs' hold over the fragile democracies of the former Soviet bloc. Today, the concept is applied more broadly for a range of dubious dealings between corporations and governments around the world.

How did state capture operate in South Africa?

Many of the revelations from the inquiry concern the relationship between two families - the Zumas, centred on the former president, and the Guptas, three Indian-born brothers who moved to South Africa after the fall of apartheid.

The two families became so closely linked that a joint term was coined for them - the "Zuptas".

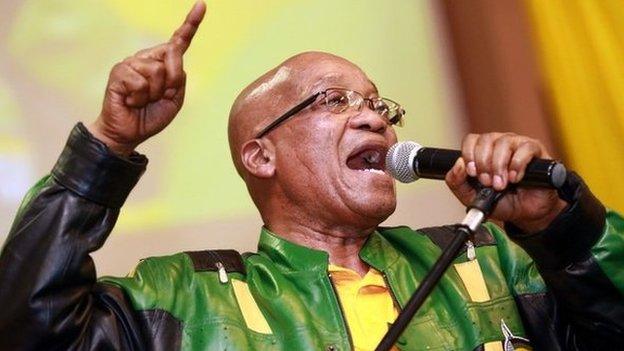

Huge protests were organised to force Jacob Zuma from power

All parties have denied the allegations against them, describing them as politically motivated.

The Guptas owned a portfolio of companies that enjoyed lucrative contracts with South African government departments and state-owned conglomerates. They also employed several Zuma family members - including the president's son, Duduzane - in senior positions.

According to testimony heard at the inquiry, the Guptas went to great lengths to influence their most important client, the South African state.

Public officials responsible for various state bodies say they were directly instructed by the Guptas to take decisions that would advance the brothers' business interests.

It is alleged that compliance was rewarded with money and promotion, while disobedience was punished with dismissal.

More about the Guptas in South Africa:

The public bodies that are said to have been "captured" in this fashion included the ministries of finance, natural resources and public enterprise, as well as the government agencies responsible for tax collection and communications, the state broadcaster SABC, the national carrier, South African Airways, the state-owned rail-freight operator Transnet and the energy giant Eskom, one of the world's largest utility companies.

The responsibility for promoting and dismissing public officials lay with Mr Zuma. According to David Lewis, executive director of Corruption Watch, a Johannesburg-based NGO that investigated the Guptas, the president's powers of appointment were key to the success of the alleged conspiracy. As well as ministers, the South African president has the right to appoint the boards of directors of state-owned enterprises and - critically - the heads of law enforcement agencies.

Mr Zuma could do as he pleased, Mr Lewis told the BBC, "as long as he ensured who was appointed the head of the police, and the head of the anti-corruption agency of the police".

What was the impact of state capture in South Africa?

The allegations eventually brought the Zuma presidency to a premature end last year and prompted the Guptas to leave South Africa.

They also damaged the reputations of various illustrious firms that had done business with the Guptas.

Ethical lapses were highlighted at the global accounting giant KPMG, management consultants McKinsey and Bain and Co, and the German IT company, SAP. Bell Pottinger, a London-based PR firm with a history of representing repressive governments, was dealt a fatal blow, closing down over its dealings with the Guptas.

Duduzane Zuma (r), son of the former president, used to work for the Gupta brothers

State capture has blown a hole through the public finances, disappearing tens of billions of dollars from Africa's most advanced economy. The scandal has also dealt a huge blow to the reputation of the African National Congress, the party that has governed South Africa for nearly 30 years. Many of Mr Zuma's colleagues in the party have, like him, been accused of corruption.

According to Dr Innes, the ultimate victim of state capture tends to be the political system that is corrupted by business interests. "Politics becomes the point of entry and exit into what is fundamentally a financial market for retaining control over the state and its assets," she said.

What can be learnt from the South African case?

The alleged conspiracy between the Zumas and the Guptas was eventually stopped by a combination of factors, including pressure from global financial markets that were alarmed by the hiring and firing of ministers in charge of the economy.

Mr Lewis argues that while the country had been let down by certain democratic institutions, such as its prosecutorial and regulatory agencies, it was rescued by others.

These included the independent media, the courts and civil society organisations - all of which had honed their skills fighting apartheid. South Africans, he said, belonged to a "young democracy with a very recent tradition of resistance to authoritarian rule. They don't take things lying down".

Mr Hellman, who testified at the inquiry, says South Africa's open discussion of the impact of state capture had set a positive example for other countries. However, he warned that there was also a risk that any such process ends up being used to settle political scores, rather than to address the "structural issues" that allowed the corruption to flourish.

Having left South Africa, the Guptas are now living in Dubai.

Jacob Zuma is currently on trial in a separate corruption case. In a 2007 TV interview, he denied that the state had been "captured".

"There is no parliament that is captured, there is no executive that is captured," he said. "State capture is political propaganda."

The interview was given to ANN7, a TV channel founded by the Gupta family. Its former editor told the state capture inquiry that Mr Zuma had been "very much involved in the running of the station".

- Published22 March 2018

- Published14 February 2018

- Published9 October 2017

- Published6 April 2018

- Published20 July 2017