The last legal sex workers in Tunisia

- Published

For decades state-regulated brothels have existed in Tunisia. They remain legal, but pressure from women's rights activists and religious conservatives has forced nearly all of them to close, as Shereen El Feki reports.

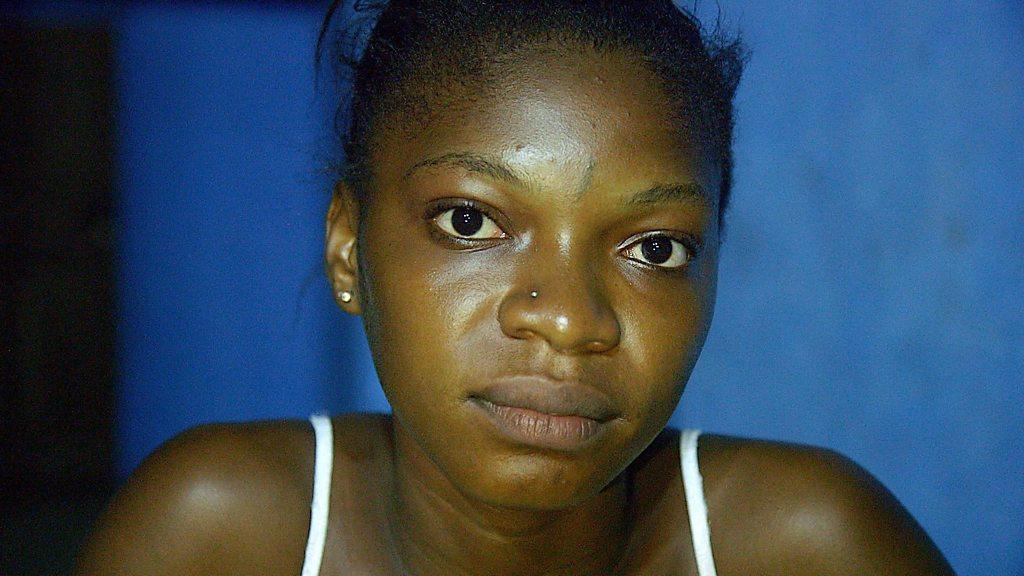

"I wake up at seven in the morning. I wash my face, I do my make-up. I go into the hall, I drink my coffee, and I wait to start our job."

Like many women in Tunisia, Amira, a single unmarried mother in her mid-20s, is working hard to make ends meet.

But Amira's job is far from usual: she is one of the few remaining legal sex workers in the Arab region.

Tunisia has a two-tier system of prostitution. One is made up of government-registered "maisons closes", or brothels, where female sex workers are authorised by the state to ply their trade. The other involves illegal freelance sex work, where the people involved risk up to two years in prison if convicted.

"We used to make a living for our children, pay our rent. We don't anymore."

Regulation of sex work, in the name of hygiene - protecting clients from sexually transmitted infections - tightened with the French occupation of Tunisia in the 19th Century.

The current laws on legal sex work were introduced in the 1940s, and survived Tunisia's independence in 1958. But for how much longer?

Before the 2010 uprising, there were an estimated 300 legal sex workers in a dozen or so sites across Tunisia. Today, only two cities - Tunis and Sfax - are home to a handful of legal brothels. They are found in tiny houses tucked away in the twisty lanes of the medina, the cities' historical heart.

'I expect to be fired'

When Amira, 25, started working in Sfax five years ago, there were 120 legal sex workers. Now she is one of a dozen left.

"Step by step they are firing women, they fire them for the simplest mistake they do. I am expecting that one day the same thing could happen to me," she said anxiously.

Infractions, such as fighting with a client or drinking in their room, are now grounds enough for dismissal.

"We used to make a living for our children, pay our rent. We don't anymore. Actually, I don't have anything else. If they kick us from there, where we would go?"

Over in Tunis, Nadia, a divorcee in her 40s, knows the answer all too well.

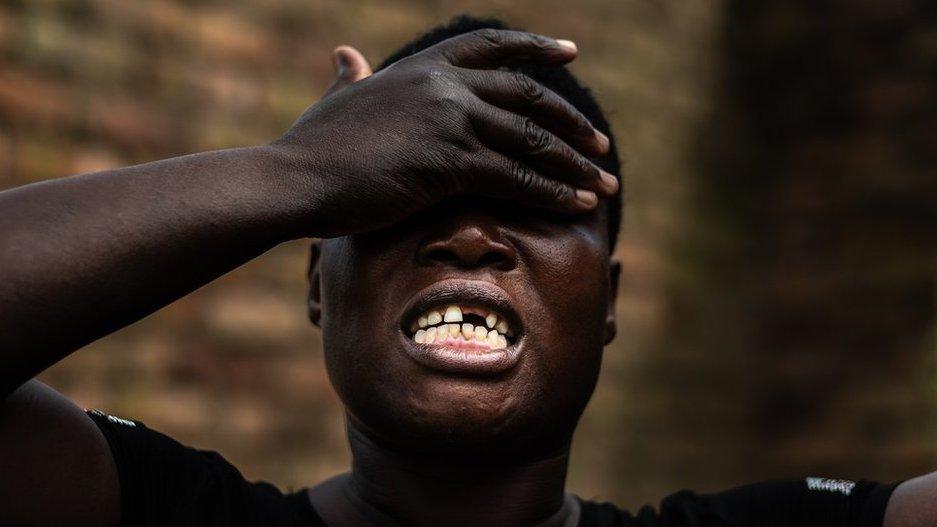

She had been working in legal brothels around the country and ended up in Gafsa, in the south. Violent protests by Salafist extremists in 2011 led to the closure of Nadia's workplace in 2011 in a wave that saw legal brothels shutting down across the country.

Once, there was a client who, after he slept with me, stole my money, beat me, and choked me"

Nadia was injured in the Gafsa attack. Once she had recovered, she had trouble fitting back in a dwindling state system and turned to illegal, street-based sex work, which is very risky.

'No-one to protect me'

She misses her life in the legal system: "It is not the same as when we were in the protected brothel, with a doctor [for weekly medical exams], a female condom and a madam [who kept an eye on proceedings]."

"Now when I get a client I am scared because I don't have anyone who can protect me or stand by my side.

"Once, there was a client who, after he slept with me, stole my money, beat me, and choked me. Now my body is full with bruises; as you can see, my nose is broken," she pointed to her battered face.

The future of sex work in Tunisia has sharply divided the country's activists, Wahid Ferchichi, a law professor at Carthage University and leading rights advocate, told the BBC.

For all the campaigns on legal reform to guarantee individual freedoms - including liberal calls for the decriminalisation of homosexuality - many women's rights activists draw the line at sex work.

"There are many in politics and civil society who support the closure [of the legal brothels], because they consider that sex work is a new kind of slavery, or human trafficking," Prof Ferchichi said.

"But if we close all these places and the Tunisian penal code is applied, we will put all these women in prison, so what is the solution?"

Downturn in sex work

A recent draft law proposes a 500 dinar ($175; £140) fine instead of jail time. But the imposition of what would be a hefty fine for the women is not popular among those who would be affected.

"It's not reasonable, in an economic situation where the country has no money and there are no jobs," said Bouthayna Aouissaoui, who runs an association for sex workers in Sfax.

Business is already down in the illegal sex trade, she observed.

Sex work has been hit by cash-strapped clients steering clear as they fear religious condemnation. Several sex workers have also spoken of growing competition from increasingly desperate women, including Tunisia's struggling migrant population.

"Five hundred dinars is too much! Where is she going to get it from?" Ms Aouissaoui asked. "She only gets 15 or 20 dinars ($5-$7) per client."

Prof Ferchichi is among the few human rights activists openly calling for decriminalisation.

He looks forward to the day "when the sex trade is decriminalised, [and] the Tunisian government will apologise to all these women who were imprisoned for this reason".

You may also be interested in:

That day will be some time in coming, so long as Ennahda, Tunisia's Islamist party, holds sway.

Meherzia Labidi, a leading Ennahda member, disagrees with decriminalisation.

"If our society's basis for its values is violated," she said, "the family will be violated, the values that we raise our children to learn will be violated."

It is not only about laws and political decisions, it is about changing mentalities"

The politician is famous in Tunisia for having met with sex workers who had been protesting against the closure of their brothels in the coastal city of Sousse in 2014.

While no fan of the legal brothels, Ms Labidi wondered about the alternatives for their residents.

"How we can we secure healthcare, housing, food and a living for them?" she asked. "By giving them a job. for example, and by making the society accept them in another way.

"It is not only about laws and political decisions, it is about changing mentalities."

If the trend of greater restrictions on sex work continues, there will be the problem of what the women who used to work in the industry can do. Jobs are hard to find in Tunisia, especially for women, whose unemployment rate is double that of men.

'Sorry I cannot hire you'

Afef, a former madam whose brothel was recently shuttered, explained the difficulties.

"Even if [a former sex worker] goes to work in a restaurant to clean dishes," she said, "one or two days later, they will say that this woman was working in a brothel and the boss would say: 'Sorry I cannot hire you.'"

Meanwhile, Amira has few hopes for the future.

"It is hard for our family to take us back. If I was kicked out of the brothel, I will go to the street, because I will beg for money for my child under the mosque. I hope they will have mercy on us."

Shereen El Feki is the author of Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World and writes for BBC Arabic

- Published16 September 2019

- Published21 May 2019

- Published26 September 2019

- Published9 October 2024