Rwanda leads fight against cervical cancer in Africa

- Published

Angeline Usanase's early diagnosis saved her life

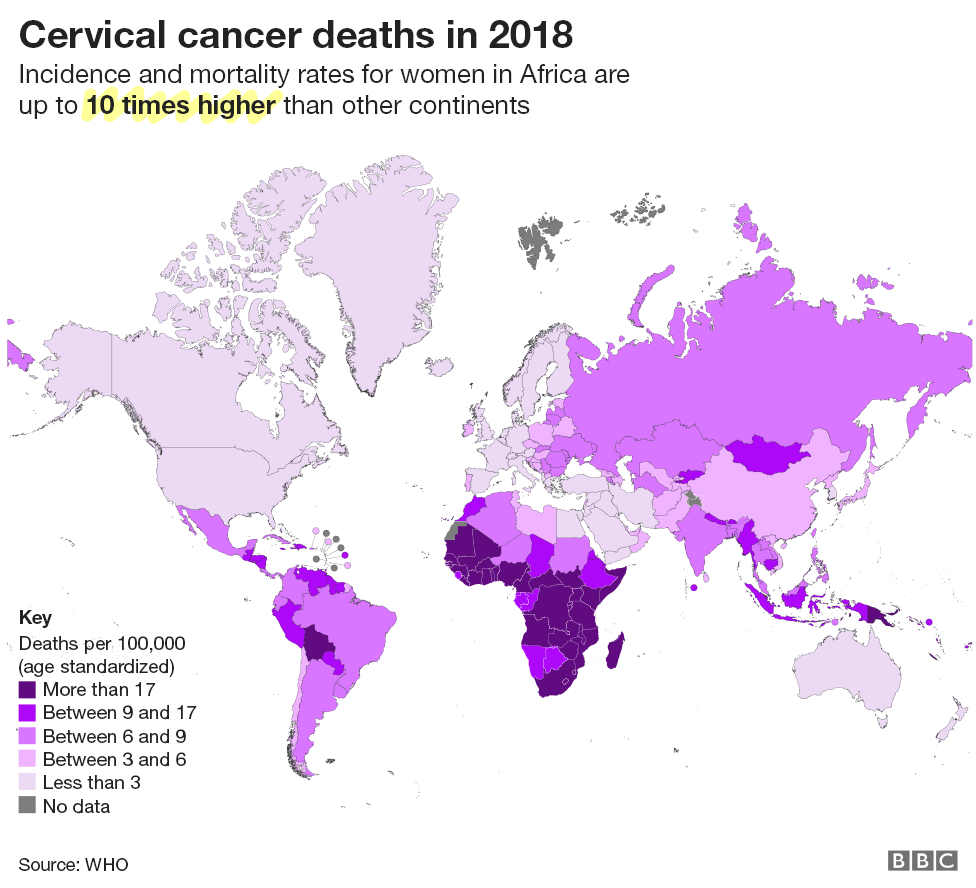

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide. But in Africa it is far deadlier than elsewhere, despite being a preventable disease. An ambitious health campaign in Rwanda has set an example which other countries on the continent are now starting to follow.

Angeline Usanase, who lives in Rwanda's capital, Kigali, remembers the day her seemingly healthy life took a drastic turn.

It was in November 2017 when she saw blood on her panties. This was no ordinary blood. At 67, Ms Usanase was menopausal and wouldn't expect even light bleeding.

"I went to a nearby health centre where the doctors recommended that I take the cervical cancer test.

"The results came back positive. I was so confused. I could not take it - I thought I was going to die," she says.

A model for success

Ms Usanase insists that the early detection and timely hospital treatment she received saved her life.

Ethiopia is among 10 African countries now offering the vaccine

But in Rwanda today, she may not have contracted the disease at all, thanks to the launch of a nationwide vaccination and cervical cancer screening campaign.

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in Africa, but it is the deadliest, according to the World Health Organization, external.

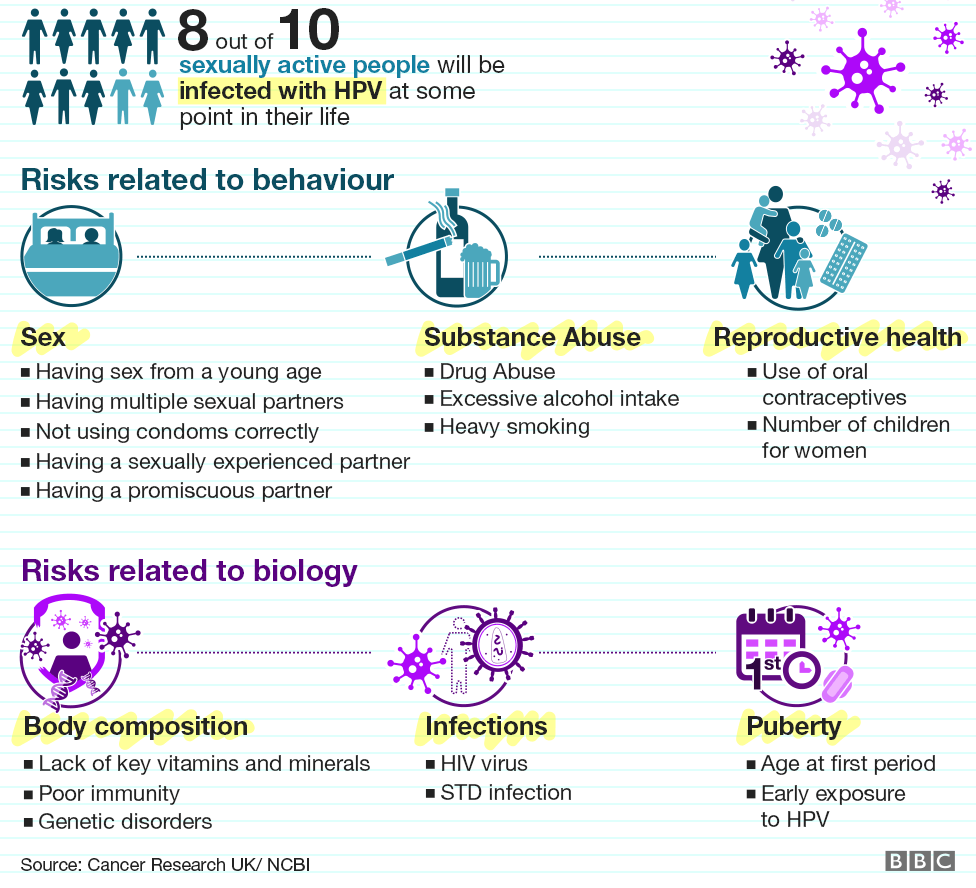

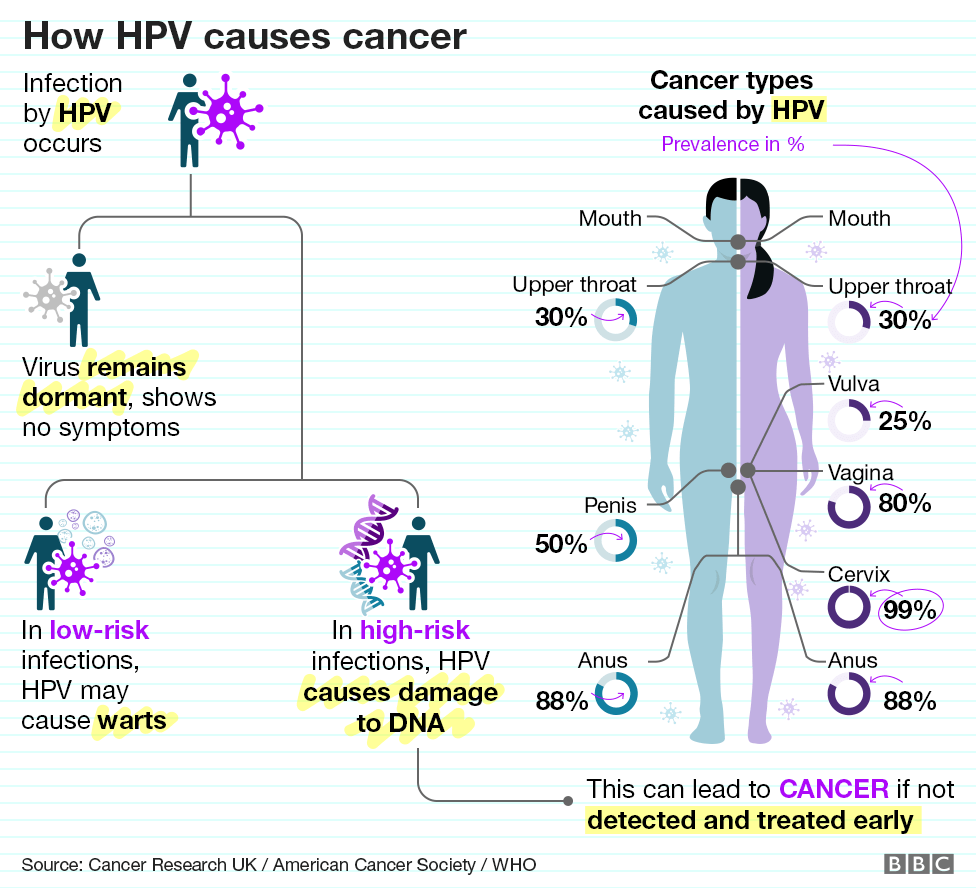

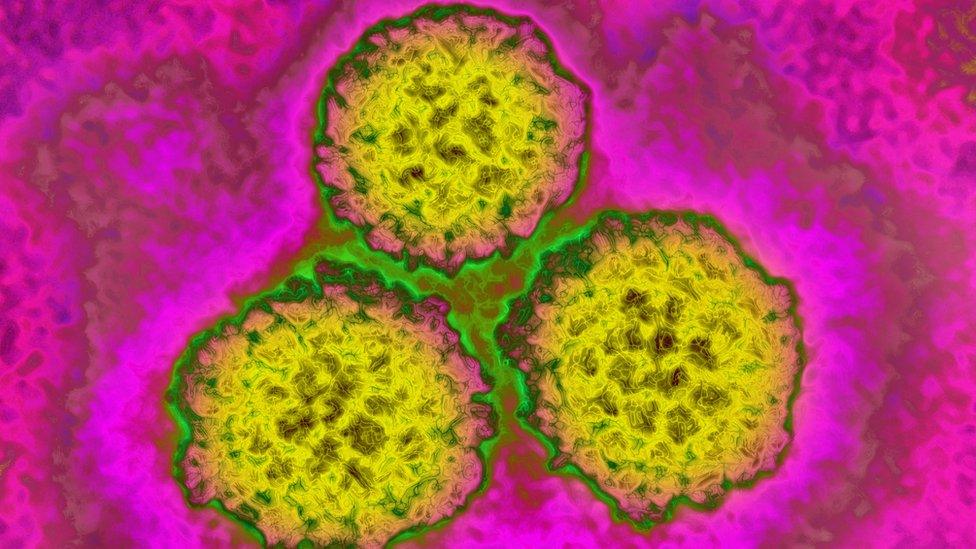

The Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), which is a sexually transmitted infection (STI), is behind almost all cervical cancer cases.

Despite the high number of deaths and the existence of an effective vaccine, only 10 African countries have, external HPV vaccination as part of their routine immunisation programmes.

Senegal is the only country in West Africa to offer it, while other countries like Nigeria ran pilot schemes but haven't adopted the vaccination at a national level.

The situation is better in East Africa, as the HPV vaccine is available in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Rwanda.

Fear of witchcraft

Rwanda launched a vigorous campaign to stem the spread of HPV and encourage women to seek early treatment for cervical cancer in 2011.

The plan was to get girls vaccinated early and to introduce cervical screening for women.

In its first year of the scheme, Rwanda reached nine out every 10 girls eligible for the vaccine, a result that analysts still cite as a model for success.

Cancer in Africa: Malawi's cervical cancer screening champion

But Rwanda's journey was not without its hurdles.

When Rwanda decided to roll out its vaccination plan, some in the global health community discouraged them, claiming that high costs would divert money needed for more pressing child health issues.

The government found a solution by partnering with an international pharmaceutical company, which provided free vaccines for the first three years of the roll-out.

There were also significant cultural barriers to overcome.

"There are still women who think cervical cancer is as a result of witchcraft and visit witchdoctors for treatment as opposed to medical doctors," says Ms Usanase.

Women also fear the prospect of having their wombs removed, she adds.

HPV is linked to cervical cancer

But surgery is a treatment for women who already have cervical cancer, not a way to prevent it.

"Cervical cancer is the most frequent cancer in Rwanda and the majority of women are coming in for treatment when it's at an advanced stage," says Dr Francois Uwinkwindi, director of the cancer control unit at the Rwanda Biomedical Centre.

Through community leaders, churches, village elders, health workers, schools and the media, the government launched a massive awareness campaign to dispel myths around the vaccine.

The vaccine was given to girls at school, and for those who weren't at school, it was offered at home.

HPV vaccination has dramatically reduced infection rates among young people

Health authorities ensured that a steady supply of vaccine was available throughout.

Eight years later, while the initial campaign started at the grassroots level, it now forms part of Rwanda's routine immunisation programme.

Although data isn't available yet to show the results in Rwanda, other countries who've taken a similar approach have seen dramatic falls in HPV infections among young people.

You may also be interested in:

Australia started mass vaccination in 2007, but had been screening women for cervical cancer since 1991.

Its current annual cervical cancer rate stands at seven cases per 100,000 people, which is about half the global average.

It is estimated that by 2020 the annual incidence of cervical cancer in Australia will fall to less than six new cases per 100,000 cases.

'Nine women die each day'

After Rwanda, other African countries are now following suit.

In October, the Kenyan government introduced HPV vaccination into the country's routine immunisation programme, working with international donors, external.

It wants to vaccinate 800,000 girls aged 10 every year.

"Nine women die of cervical cancer daily in Kenya. This is a move to prevent the disease through vaccination for girls and screening of older women," said Marleen Temmerman, a professor of obstetrics and gynaecology at the Aga Khan University Hospital in Nairobi.

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta watches a girl receiving the HPV jab

Some however still don't trust the vaccine, despite global health authorities declaring it to be safe and effective, with only minor side effects.

"I haven't taken my 10-year-old because I'm afraid of what I'm hearing. There are rumours that our children will become paralysed or they will get blood clots. We have not received education on the vaccine," says Mbonje Athman, a mother living in the coastal city Mombasa.

The Kenya Catholic Doctors Association (KCDA), a religious group, has called for a boycott of the vaccine, saying it is unnecessary to give it to young girls, and urging monogamy and sexual abstinence as a way of avoiding HPV.

Back in Rwanda, the plan is to scale up efforts to beat cervical cancer.

"Many older girls and women didn't get a chance to be immunised when we started the roll-out so now the strategy is to target and screen women between 30 and 49 years," says Dr Uwinkwindi.

Ms Usanase now shares her own cancer story as a way of raising awareness and encouraging others to seek out treatment to prevent the disease.

"If I had my way, I would line up everyone and get them to go see a doctor," she says.

- Published25 November 2019

- Published25 November 2019

- Published4 April 2019

- Published19 January 2018

- Published13 February 2019

- Published30 October 2018