Why France is focused on fighting jihadists in Mali

- Published

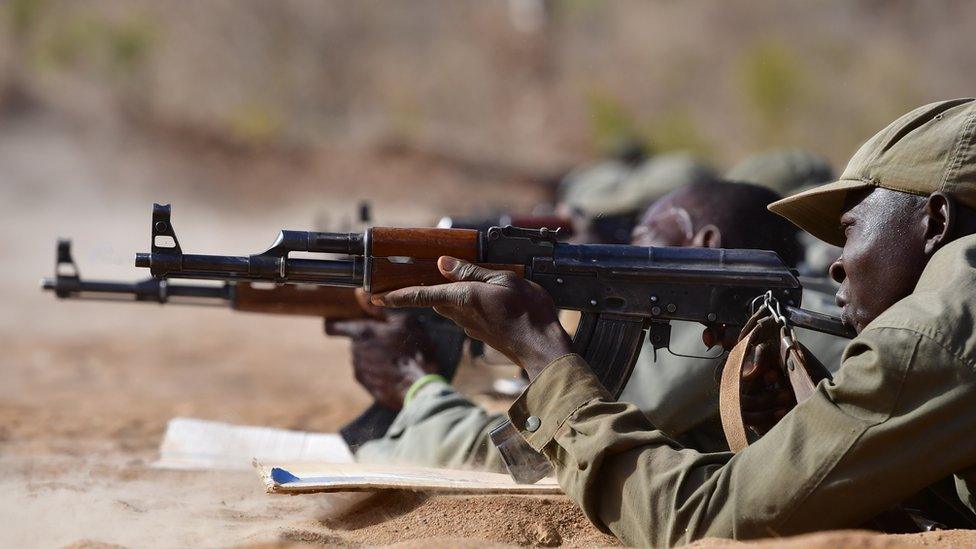

Malian soldiers operate in difficult terrain where temperatures can climb to around 50C

As jihadist violence escalates in Mali, analyst Paul Melly considers if France can persuade the rest of Europe to join the deadly fight.

Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly has called on fellow EU governments to despatch special forces to the Sahel, to help curb militant attacks that have killed more than 100 Malian troops in recent weeks.

But France, too, is paying a heavy price for its role in the struggle against Sahel jihadism, with the death of 13 soldiers when two helicopters collided on Monday.

Altogether, it has lost 38 troops in this almost seven-year campaign.

Murderous ambushes

Extremist violence, sometimes intermingled with criminal trafficking or local community tensions, is disrupting everyday life and any hopes of development in this desperately poor region, which fringes the Sahara.

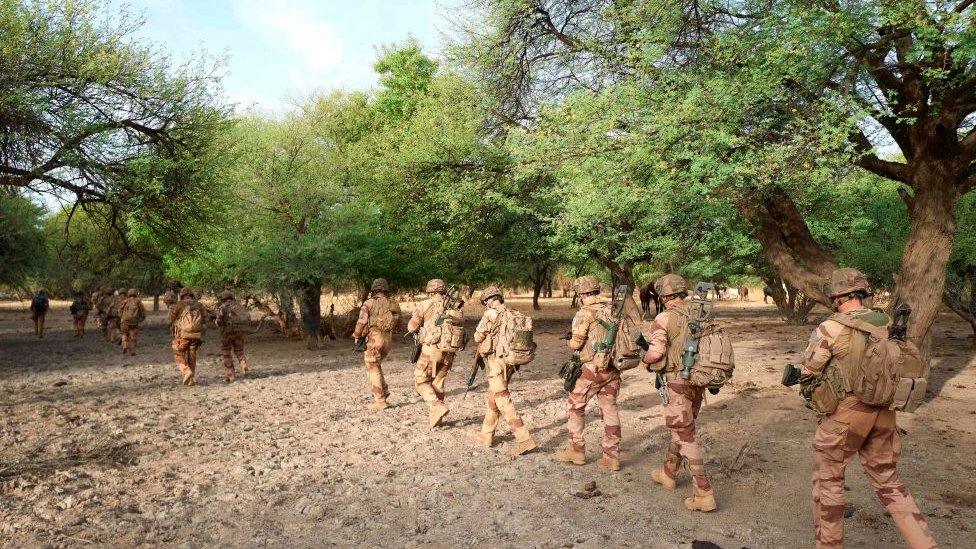

European allies have been lending the Mali army some support

But the causes are complex and neither negotiations nor military operations have yet managed to restore security.

Indeed, the crisis appears to be getting worse.

Despite Sahelian countries' creation of a joint force to tackle jihadists, and the presence of 4,500 French soldiers and more than 14,000 UN peacekeepers, this year has seen the jihadist groups step up their war against Mali and its international allies.

In the central regions jihadist activity is led by the charismatic preacher Amadou Koufa, who is Fulani, a largely Muslim ethnic group of semi-nomadic herders known in Mali as the Peulh.

This has become interwoven with tensions over resources such as land, grazing and water, undermining relations with another local Muslim ethnic group, the Dogon, some of whom have formed their own rival militia.

Further east, dubbed the "three frontiers region" where Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger converge, has seen repeated cross-border attacks by armed groups, one of which claims allegiance to the Islamic State (IS) group.

Militants have staged a string of murderous ambushes, extended their activity across much of Burkina Faso and even kidnapped two tourists from a national park in northern Benin, confirming fears that they could soon pose a threat to coastal countries from Ivory Coast and Ghana to Nigeria.

Mali 'not forgotten'

This is not an African crisis that has been ignored by the rest of the world. Quite the contrary in fact.

It features regularly in discussions of the UN Security Council and the UN operation in Mali (Minusma), includes troops from Asia, Canada and Europe as well as Africa.

France, which intervened in Mali in 2013 to stop jihadists moving south, now runs an anti-insurgent operation across the Sahel

Moreover, since 2013 the EU has been retraining the Malian army, while the French anti-terrorism force, Operation Barkhane, deployed across the Sahel is supported by British helicopters, other European allies as well as US surveillance drones.

Main jihadist groups:

Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (GSIM), alliance of jihadists, comprising:

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (Aqim)

Ansar Dine, led by GSIM overall leader Iyad Ag Ghaly

The Macina Liberation Front, led by Amadou Koufa

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), affiliated to IS, active in north-east Mali

Ansarul Islam, active in northern Burkina

Yet the security crisis continues to deepen.

Minusma is the most dangerous UN mission in the world, having lost 206 personnel over the past six years.

Overseeing the fragile 2015 peace deal between the Mali governments and those groups that are not engaged in jihadist violence, the Blue Helmets force is trying to support local communities.

But with supply lines extending over many hundreds of kilometres to their isolated bases, its troops are highly vulnerable.

Minusca troops often feel vulnerable

However, it is the armies of the G5 Sahel countries (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Mauritania and Chad) themselves that bear the brunt of the jihadist campaign.

They are desperate for more international funding and equipment for their own 5,000-strong joint force.

The Malian army in particular is struggling to cope: far from the capital, Bamako, in difficult terrain where temperatures can climb to around 50C in hot months, soldiers are at risk both when they move on patrol and when they barricade themselves into isolated rural garrison bases.

You may also be interested in:

What is behind Mali's massacres?

This year has proved especially lethal: the deaths of more than 100 Malian soldiers in ambushes at Boulikessi (in Mopti region), Indélimane and Tabankort since late September have struck a brutal blow against the morale of an army that already feels under-equipped and short of support.

French troops, supported by helicopters and Mirage 2000 strike planes, provide emergency back-up whenever they can.

But they are covering a vast region where, even with US surveillance drone support, it is hard to track down small bands of militants, darting across the arid terrain on motorbikes.

Jobs not guns

Everyone is agreed that military action alone cannot bring an end to the violence and restore stability.

Main militias (not jihadist):

Co-ordination of Azawad Movements (CMA), former Tuareg separatists who signed the 2015 peace deal, including:

National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA)

The High Council for Unity of (HCUA)

The Platform, a pro-government alliance of militias in northern Mali who signed the 2015 peace deal, including:

The Imghad Tuareg Self-Defence Group and Allies (Gatia), led by Ag Gamou

Ganda Koy (meaning Masters of the Land)

The Movement for the Salvation of Azawad (MSA)

Dan Na Ambassagou (meaning Hunters who trust in God), a Dogon militia launched in central Mali in 2016, in theory dissolved by government but still a factor

Health, education, justice and basic administration are needed to build community support for the Malian state.

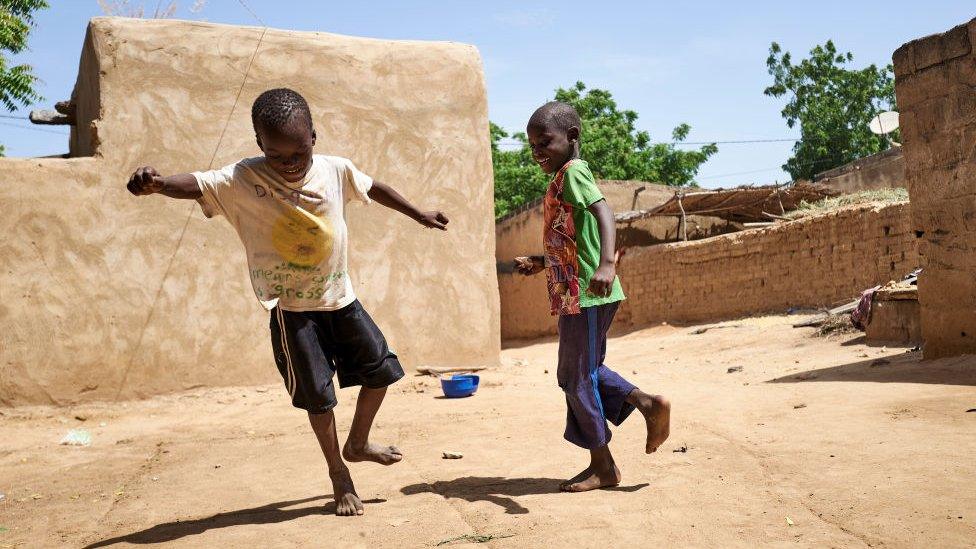

More jobs and livelihoods could reduce the risk of disenchanted young men being drawn into jihadist groups or criminal gangs offering money and the status that can come with carrying a weapon.

A wide range of donors have committed large aid budgets to the Sahel, motivated by concern over poverty and climate change in this fragile region so prone to drought - and also by fear of the knock-on impact of terrorism and a potential resurgence in the flow of migrants across the Sahara and Mediterranean.

More jobs would stop children being lured into jihadist groups with the promise of money

But even with ample aid support, it is difficult to provide effective public services or grassroots economic development when conditions are so insecure and government employees face intimidatory threats and sometimes the risk of assassination.

Mistrust hampers progress

In central Mali there have been some negotiations at community level that could develop into a more sustained local peace process.

But it is fragile at best, hampered by mistrust as well as reluctance at a political level.

These Fulani militiamen went to hand in their weapons earlier this year

Further north, there has been some progress in the demobilisation of fighters from the armed groups signed up to the 2015 peace accord.

The intention is that many of these should be absorbed into special integrated army units, to reinforce local security.

But here too, progress has been fitful, and not helped by the government's reluctance to fully develop public services in Kidal, the north-eastern regional capital still under the control of former Tuareg separatists, even though the latter are signatories of the peace accord.

The present military approach being pursued by the Sahel armies and their international partners is not working, at least not sufficiently - and France is well aware of the need for a fresh approach.

This is one of the world's poorest regions and a much greater focus on development is essential. But that still cannot happen without better security.

That is why - despite the shocking loss of 13 men in this week's helicopter crash - President Emmanuel Macron remains committed to the military campaign, in alliance with Sahelian governments.

But Paris is desperate for other European countries to do more to help share the burden.

Paul Melly is a consulting fellow with the UK-based think-tank Chatham House and a journalist who specialises in Francophone Africa.

- Published28 July 2023

- Published28 June 2019