FW de Klerk and the South African row over apartheid and crimes against humanity

- Published

Nelson Mandela (L) and FW de Klerk jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993

FW de Klerk, the last white man to lead South Africa, has apologised for "quibbling" over whether or not apartheid was a "crime against humanity", but the row has revealed old wounds, writes the BBC's Africa correspondent Andrew Harding.

The past is still raw in South Africa.

Mr De Klerk's apology was an attempt to calm a fortnight of increasingly furious debate after he made comments that many interpreted as an attempt to rewrite history and play down the seriousness of apartheid.

In a statement issued through the De Klerk Foundation, the 83-year-old expressed regret for "the confusion, anger, and hurt" his remarks might have caused.

Two weeks ago, in an interview with the national broadcaster, SABC, the former president said he was "not fully agreeing" with the presenter who asked him to confirm that apartheid, the legalised discrimination against non-white people, was a crime against humanity.

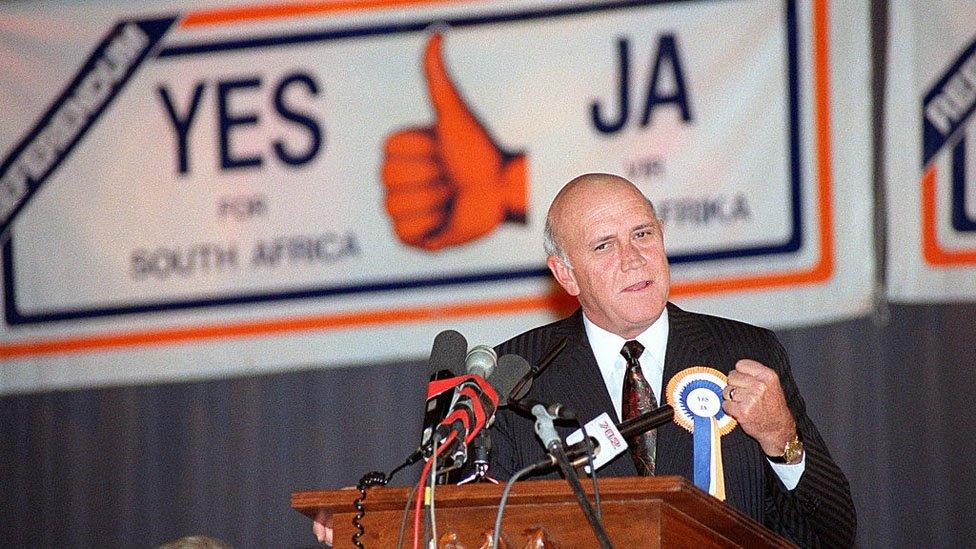

In 1992, FW de Klerk campaigned in a white-only referendum to get backing for reforms to end apartheid

Mr De Klerk went on to acknowledge that it was a crime, and to apologise profusely for his role in it, but he insisted that apartheid was responsible for relatively few deaths and that it should not be put in the same category of "genocide" or "crimes against humanity".

At first, South Africa seemed to shrug.

Mr De Klerk, who shared the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize with Nelson Mandela after helping to negotiate an end to apartheid, is a peripheral figure in the country these days, and his potentially polarising comments seem to pass unnoticed.

Julius Malema led members of his EFF party to get Mr De Klerk removed from parliament

But that changed last Thursday when, as a former head of state, he attended parliament for President Cyril Ramaphosa's annual State of the Nation address.

Members of the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party interrupted the president and demanded that Mr De Klerk be removed from the chamber.

"We have a murderer in the House," said EFF leader Julius Malema. He said that Mr De Klerk was an "apartheid apologist… with blood on his hands".

An hour-and-a-half later, President Ramaphosa was finally able to begin his speech, and the EFF's aggressive delaying tactics were widely condemned - by the governing ANC and other opposition parties - as an outrageous, shameful stunt.

You may also be interested in:

Once again, it seemed as if Mr De Klerk's own comments had been more or less sidelined.

But not for long.

In the days that followed, the backlash against Mr De Klerk gathered a furious momentum across the country, opening wounds and provoking deep anger. That anger was fuelled - in part - by social media, and by rival political agendas, but also by the former president's blunt attempts to defend his views.

His own charitable foundation initially issued a defiant statement explaining why it believed Mr De Klerk was right to insist that apartheid was not a crime against humanity.

It argued that describing it as such was simply "an agitprop project initiated by the Soviet Union", and that it was "simplistic" to portray South Africa's painful history in a "black/white, good/evil framework".

Mr de Klerk, his foundation insisted, was an innocent victim of the EFF's "bully boy tactics... who whip up race hatred and call their leaders 'Führer, or Duce'".

FW de Klerk defended his record last week

In a BBC interview last Friday, Mr De Klerk said his comment about crimes against humanity was "in line with the (UN) Security Council at that time".

This was a reference to the fact that, although the UN General Assembly declared that apartheid was a crime against humanity, the US and the UK (both permanent members of the Security Council) voted against approving this description.

But this cannot obscure the UN's repeated condemnation of apartheid and imposition of wide-ranging sanctions against South Africa. Apartheid was also included as a "crime against humanity" in the Rome Statute that set up the International Criminal Court.

'Shock' at De Klerk's ignorance

"It is unarguable and hopeless to claim today that apartheid is not, and has never been, a 'crime against humanity,'" said Philippe Sands, QC, a professor and expert on international law.

To push home that same point, another former South African President, Thabo Mbeki, announced that he would send Mr de Klerk a copy of the relevant UN convention, having been shocked to learn from the man himself that his predecessor "actually did not know" about its existence.

Some voices - particularly, but not exclusively, those of white South Africans - responded to Mr De Klerk's comments by calling for people to "move on" and to focus on more urgent priorities like fighting corruption, tackling poverty, and reviving a stagnant economy.

Those same voices suggested that the furore was being deliberately, cynically, exploited by the ANC and others, in order to deflect attention from its own failings, and to shift blame to the white minority.

There is no doubt that in recent years, under former President Jacob Zuma, and spurred on by the EFF, the political rhetoric in South Africa has become increasingly racialised. White farmers and "white monopoly capital" have frequently been blamed for the country's slow pace of economic transformation.

People queued in their millions to vote in South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994

The former leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance, Helen Zille, has regularly bemoaned the growth of racial nationalism, and of "identity politics" which has also caused friction within her own party.

But to many others here - perhaps even to the majority - Mr De Klerk's comments appeared to reinforce a wider perception that many white people have never been obliged to confront, properly, the evils of the past. This is in part, perhaps, because apartheid ended through negotiation rather than a military victory.

"Far too many white South Africans… continue to deny the full horror of apartheid," wrote constitutional expert Pierre de Vos. "[They] refuse to admit that they or their parents actively, or tacitly, propped up the system and still reap the benefits bestowed on them by that system."

'De Klerk should repent'

"Sadly, FW de Klerk, his foundation, and the behaviour of some of our white compatriots of even trying… to justify the systemic destruction of black lives for generations, has opened old wounds at the time when many are questioning the very democracy and its liberation dividends," wrote political commentator Somadoda Fikeni on Twitter.

"De Klerk soaked up the glory and the money on the speaking circuit when he should have repented every single day," tweeted prominent journalist Carol Paton.

The ANC issued its own statement, condemning Mr De Klerk's argument as "a blatant whitewash [which]… flies in the face of our commitments to reconciliation and nation building".

It is incumbent on former leaders of the white community... to demonstrate the courage... necessary to contribute to societal healing"

Soon afterwards, Archbishop Desmond Tutu's foundation called on the De Klerk Foundation to "withdraw its statement".

It angrily chided the former president: "It is incumbent on leaders and former leaders of the white community, in particular, to demonstrate the courage, magnanimity and compassion necessary to contribute to societal healing."

This row has surfaced at a particularly difficult time. As Desmond Tutu himself put it in his foundation's statement, South Africa "is on an economic precipice. It is beset by radical poverty and inequity. Those who suffered most under apartheid continue to suffer most today."

Some black South Africans have taken to arguing that Mr Mandela himself was a sell-out, and that the painful and hard-won compromises that led to the emergence of a democratic "rainbow" nation, now need to be re-examined.

In his second statement, withdrawing his first, Mr De Klerk acknowledged that his comments about apartheid had been "totally unacceptable".

- Published13 February 2020

- Published11 August 2018

- Published30 May 2018

- Published24 June 2013