Viewpoint from Sudan - where black people are called slaves

- Published

Reem Khougli and Issam Abdulraheem faced abuse for marrying each other

In our series of Letters from African journalists, Zeinab Mohammed Salih writes about the horrific racial abuse black people experience in Sudan.

Warning: This article contains offensive language

As anti-racism protests swept through various parts of the world following African-American George Floyd's death in police custody in the US, Sudan seemed to be in a completely different world.

There was little take-up in Sudan of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. Instead many Sudanese social media users hurled racial abuse at a famous black Sudanese footballer, Issam Abdulraheem, and a light-skinned Arab make-up artist, Reem Khougli, following their marriage.

"Seriously girl, this is haram [Arabic for forbidden]... a queen marries her slave," one man commented on Facebook after seeing a photo of the couple.

Facebook Live from honeymoon

There were dozens of similar comments - not surprising in a country where many Sudanese who see themselves as Arabs, rather than Africans, routinely use the word "slave", and other derogatory words, to describe black people.

Sudan has always been dominated by a light-skinned, Arabic-speaking elite, while black Africans in the south and west of the country have faced discrimination and marginalisation.

It is common for newspapers to publish racial slurs, including the word "slave".

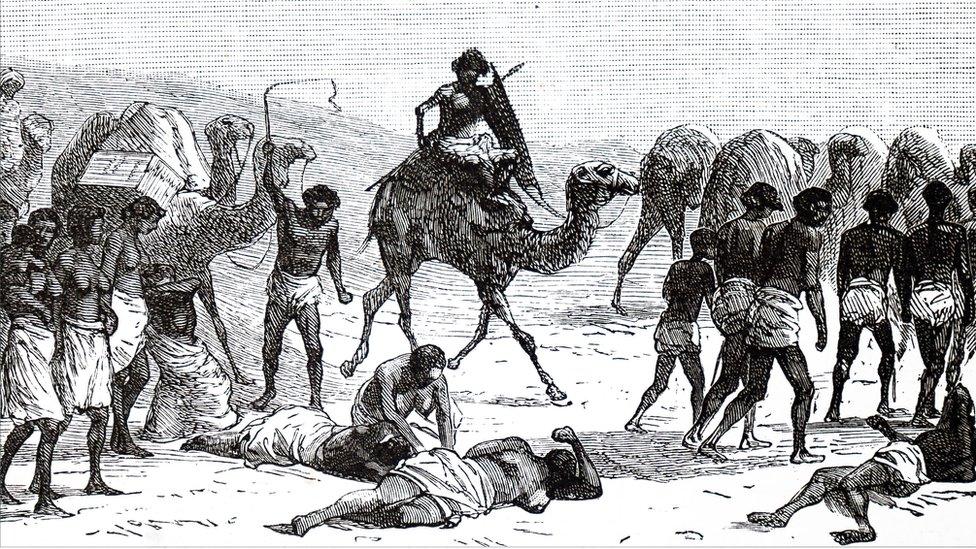

Sudan was a major slave-trading area in the 19th Century

A few weeks ago, an Islamist columnist at Al-Intibaha, a daily newspaper supportive of ex-President Omar al-Bashir, who does not approve of women playing football, referred to the female football coach of the Gunners, a well-known youth team for girls, as a slave.

And almost all media outlets describe petty criminals in the capital, Khartoum, as "negros" as they are perceived to be poor and not ethnically Arab.

When I asked Abdulraheem for his reaction to the racial abuse hurled at him and his wife, he said: "I couldn't post more pictures on my social media pages for fear of receiving more [abuse]."

Instead, the 29-year-old and his 24-year-old wife did a Facebook live during their honeymoon, saying they were in love and their race was irrelevant.

Few black faces

In another recent instance, the head of a women's rights group, No To Women Oppression, commented on a photo showing a young black man with his white European wife by saying that the woman, in choosing her husband, may have been looking for the creature missing on the evolutionary ladder between humans and monkeys.

Following an outcry, Ihsan Fagiri announced her resignation, but No To Women Oppression refused to accept it, saying she did not mean it.

There have been some small anti-racism protests in Sudan

Racism is insidious in Sudan, historically and since independence when most senior positions have been filled by people from the north - the Arab and Nubian ethnic groups.

Almost all senior military officers are from these communities, which has also allowed them to use their influence to dominate the business sector.

Today if you go into any government department or bank in Khartoum, you will rarely see a black person in an important role.

There are no reliable statistics on the ethnic breakdown of Sudan's population, let alone their relative wealth, but a Darfuri-based rebel group fighting for the rights of black people estimates that 60% of Khartoum residents are black.

Slave traders 'glorified'

The racism goes back to the founding of Khartoum in 1821 as a marketplace for slaves.

By the second half of the century about two-thirds of the city's population was enslaved.

Sudan became one of the most active slave-raiding zones in Africa, with slaves transported from the south to the north, and to Egypt, the Middle East and the Mediterranean regions.

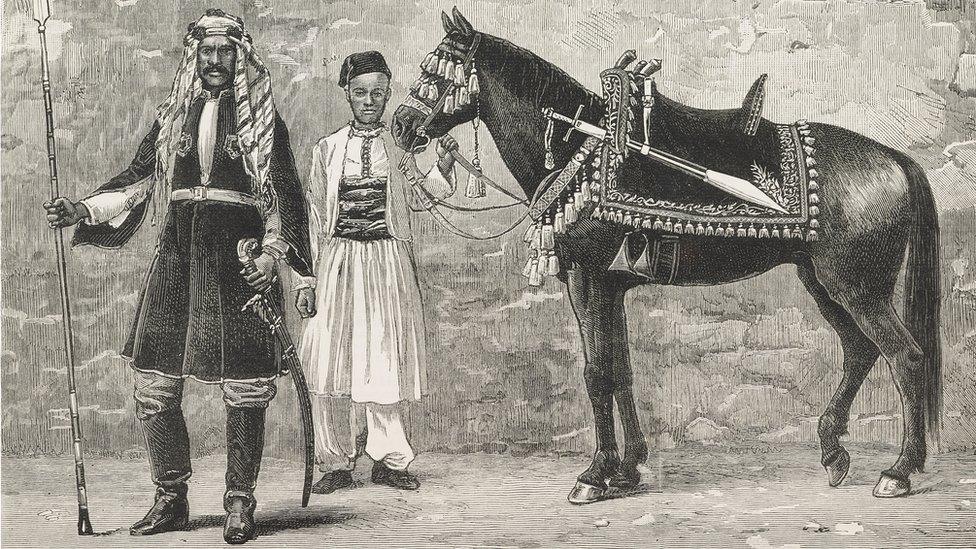

Al-Zubair Pasha Rahma was a powerful slave trader

Slave traders are still glorified - a street in the heart of the capital is named after al-Zubair Pasha Rahma, whose 19th Century trading empire stretched to parts of what is now the Central African Republic and Chad.

Historians say he mainly captured women from the modern-day Sudanese areas of Blue Nile and the Nuba Mountains, as well as South Sudan and Ethiopia's Oromia region. He was also known for his slave army, made up of captives from South Sudan, which fought for the Ottomans.

Another street is named after Osman Digna - a slave trader and military commander, whose lucrative business was curtailed by the then-British colonial administration when it moved to outlaw slavery.

The practice was only officially abolished in 1924, but the decision faced strong resistance from the main Arab and Islamic leaders of that era, among them Abdelrahman al-Mahdi and Ali al-Mirghani, who many believe had slaves working on the vast tracts of land they owned along the Nile River.

The superiority complex of many Arabs lies at the heart of some of the worst conflicts in Sudan"

They wrote to the colonial administration urging them not to abolish slavery, but their request was ignored.

The two men, along with their political parties - Unionist and Umma - continued to wield enormous influence after independence, entrenching notions of Arab superiority in the new state by reserving almost all jobs for Arabs and failing to develop areas inhabited by black people.

Mahdi's grandson, Sadiq al-Mahdi, served as prime minister from 1966 to 1967 and again from 1986 to 1989, when Mirghani's son, Ahmed, became president in a coalition government the two men had formed.

Two Sudanese academics, Sulimen Baldo and Ushari Mahoumd, publicly alleged in 1987 that they had uncovered evidence of some northern-based Arab groups enslaving black people from the south. They say these groups were armed by Sadiq al-Mahdi's military - and were the genesis of the Janjaweed militias, which were later accused of ethnic cleansing in Darfur.

Sadiq al-Mahdi has been on the political scene for more than 50 years

The slave-raiding allegations were denied at the time by the government of Ahmed Mirghani and Sadiq Mahdi, who remains influential in Sudanese politics and is close to the current government, which took power after the overthrow of Mr Bashir in 2019.

21st Century slave raids

The superiority complex of many members of the Arab elite lies at the heart of some of the worst conflicts to hit Sudan since independence, as black people either demand equality or their own homeland.

The southern slave raids were widely reported to have continued until the end of the civil war in 2005, which led to the mainly black African South Sudan seceding from Arabic-speaking Sudan five years later.

The women and children abducted by Arab groups to work for a "master" for free often never saw their families again, though in some cases their freedom was controversially bought by aid groups such as Christian Solidarity International, external.

You may also be interested in:

And since the Darfur conflict started in the early 2000s, the pro-government Arab Janjaweed militias have repeatedly been accused of arriving on horseback in black African villages, killing the men and raping the women.

Little has changed there in the last year, with reports of rapes and village burnings continuing despite the peace talks organised by the power-sharing government, which is leading the three-year transition to civilian rule.

Mass atrocities have been carried out in Darfur

The transitional government was formed by the military and the civilian groups that led the 2019 revolution, but it is unclear whether it is genuinely committed to tackling the structural racism within the Sudanese state.

The Sudanese Congress Party (SCP), a key member of the civilian arm of the government, says that a law has been proposed to criminalise hate speech. Under the proposal, the punishment for using racial slurs would be five years in jail, SCP spokesman Mohamed Hassan Arabi told me.

But many black people are uneasy about the military's role in government, given it was part of Mr Bashir's regime.

One of the few black ministers, Steven Amin Arno, quit within two months of taking office, saying in a resignation letter which appeared on social media that nobody was listening to him.

The government did not comment on his allegations, which he says proves his point.

"What happened with me shows the marginalisation and the institutional racism in the country," he told me.

More Letters from Africa:

Follow us on Twitter @BBCAfrica, external, on Facebook at BBC Africa, external or on Instagram at bbcafrica, external

- Published13 September 2023

- Published12 February 2020