The Cameroonian waging war against a French war hero’s statue

- Published

Cameroonian activist Andre Blaise Essama has been on a decades-long mission to purge his country of colonial-era symbols, long before the issue came to international prominence in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests.

His main target has been French World War Two hero Gen Philippe Leclerc in the country's biggest city, Douala.

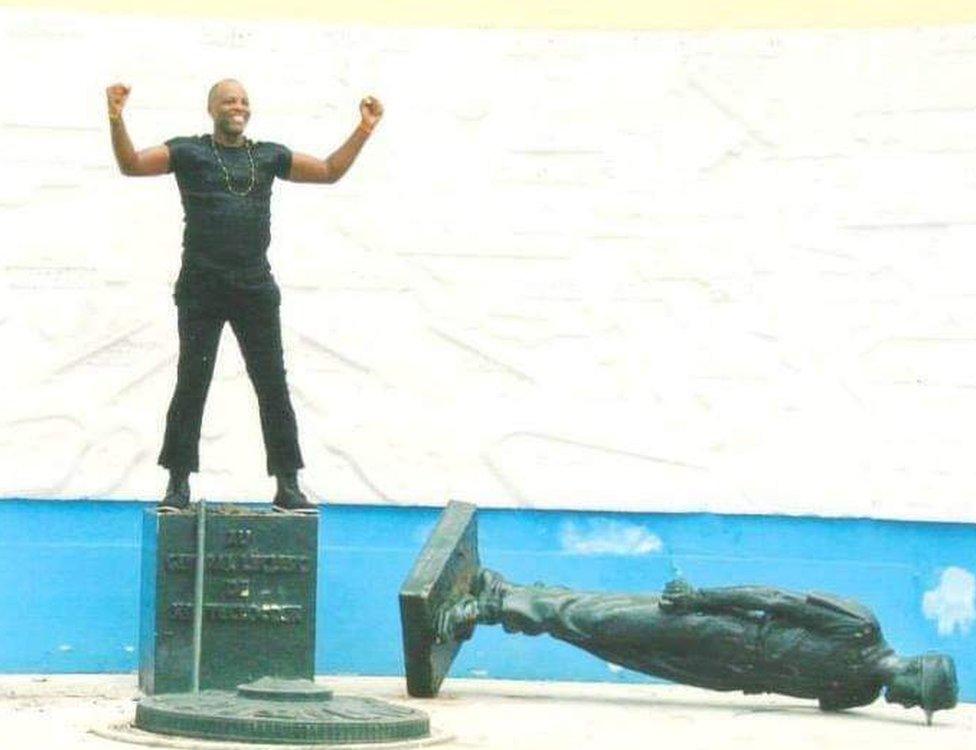

"I have decapitated Leclerc's head seven times and toppled the statue at least 20 times," Mr Essama told the BBC.

"I use my bare hands... but I make an incantation to the ancestors first," he said.

Andre Blaise Essama first toppled Gen Leclerc's statue in 2003

His aim is to replace them with Cameroonian and other African heroes, but he will make an exception for those who campaigned for "the good of humanity".

He is especially keen on erecting a statue of Diana, the late Princess of Wales.

"Diana was against racism and she stood for humanity. We loved her here in Cameroon," Mr Essama said.

Mr Essama has also targeted a statue of Gustav Nachtigal, who arrived in Cameroon in 1884 to establish a German empire.

During World War One, British and French troops forced the Germans out, later splitting the German-occupied territory between them.

Seven heads restored

The authorities see his activities as vandalism, arguing that African heroes can be celebrated without removing colonial symbols.

Mr Essama has been imprisoned several times for cutting the head off Gen Leclerc's statue - serving up to six months at a time.

Sometimes he has avoided a jail term by paying fines, with the money mostly raised by his supporters in Cameroon and in the diaspora.

Each time he has damaged Gen Leclerc's statue in the main square in Douala, the authorities have restored it.

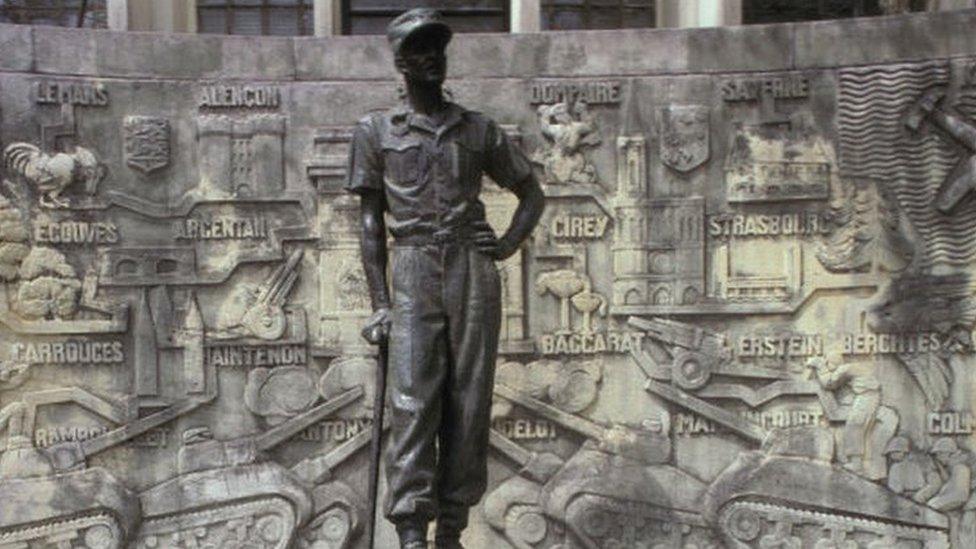

Gen Leclerc's statue was put up in Douala before Cameroon's independence in 1961

With one hand on hip, the other holding a walking stick, the French hero stands on a plinth in front of a curved stone relief depicting the French World War Two military arsenal, including tanks and planes.

It was erected by the French colonisers in 1948, long before Cameroon became independent in 1960.

'Seen as a god in France'

In France, Gen Leclerc is celebrated for his role in rallying troops in the 1940s in France's then-colonies to fight the German occupation.

"Leclerc is the great hero who helped liberate France... so the French regard him as a god," a history professor at the UK's Oxford University, Robert Gildea, told the BBC.

Gen Leclerc has come to represent the erasure of Cameroonian colonial memory and replacing it with a French one"

But he was unpopular in Cameroon, retired Cameroonian academic Prof Valere Epee said.

"Cameroonians didn't like him because he seemed not to care for the people.

"He was not like French President Charles de Gaulle, who visited Cameroon twice, and whom people seem to have an affection for."

Gen Leclerc died in a plane crash in Algeria in 1947, three years after the liberation of Paris. Thousands of people lined the streets in the French capital to pay tribute to him.

Several memorial plaques have been installed in his honour in France, two streets in Paris have been named after him and a military tank, still in service, bears his name.

'Our heroes first'

His venerated status does not impress Mr Essama.

"He is not our hero," says the 44-year-old activist, who is a computer science graduate.

Gen Leclerc's statue is used by the activist to educate people about colonialism

"Gen Leclerc has come to represent the erasure of Cameroonian colonial memory and replacing it with a French one."

Mr Essama has collected seven heads of Gen Leclerc over the years, and has occasionally taken them on to the streets to "sensitise Cameroonians about the country's history".

He says he was inspired by Cameroonian nationalist Mboua Massock, who once graffitied the general's statue with the words: "Our own heroes and martyrs first."

"We sing in our anthem, 'Oh Cameroon land of our ancestors.' How is it that our ancestors are not represented in public spaces?"

In 1991, Cameroon's President Paul Biya signed a declaration to rehabilitate the memory of the country's heroes who had been denigrated because of their role during the fight for independence.

"Not much has been done since the law was signed," Mr Essama said.

French hero 'now behind bars'

A history professor at the University of South Africa, Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, says that statues and monuments "have become soft targets in the struggle against decolonisation".

Andre Blaise Essama is pleased that football star Samuel Mbappé Léppé has been honoured

"The Europeans were thinking they were the only people on earth and, therefore, there was emptiness outside Europe, which was waiting to be discovered," he told the BBC, quoting the late American anthropologist James Blaut's views on Eurocentrism.

"If you follow that logic: you discover a place, you name it, eliminate what you find there, then you conquer, then you own it, and statues are symbols of ownership," he said.

"In the former colonies, the statues mean that the colonisers have not repented for the sins they committed against the local people but their presence in the home country means that this is the conqueror of the world, this is our hero."

He dismisses the argument that statues should be protected because of their historical significance.

"If your statue is history, the indigenous people are saying: 'But you wrote your history on top of my history. It is overshadowing our own histories.'"

You may also be interested in:

What do we do with the UK's symbols of slavery?

Prof Ndlovu-Gatsheni said the targeting of statues was part of a multifaceted campaign by Africans.

"There are those who topple statues, others want to stop the use of West Africa's CFA currency [which is pegged to the euro], others are pushing for reparations, all these are part of the struggle against the empire."

As for Mr Essama, he is now less focussed on decapitating statues, turning his attention to fundraising to build statues of Cameroonian heroes and calling for reparations for colonial-era crimes.

A statue of John Ngu Foncha, a leader from the Anglophone regions of Cameroon, was installed after Essama's campaign

So far his advocacy group, Essama Hoo Haa, has helped install two statues.

One is of Samuel Mbappé Léppé, considered Cameroon's best ever footballer, "better than Roger Milla and Samuel Eto'o", Mr Essama says.

The other is of John Ngu Foncha, a former prime minister who championed the cause of greater autonomy for Cameroon's mainly English-speaking regions.

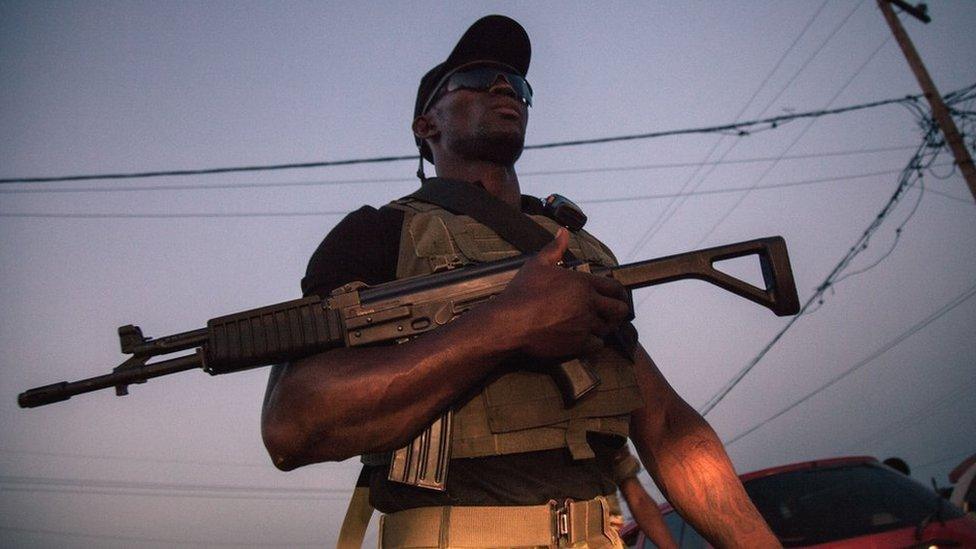

Gen Leclerc's statue does still occupy Mr Essama's mind, though it has become more difficult to target because it is now sealed off and has guards protecting it.

"He is in prison," Mr Essama said with a wry chuckle.

- Published9 March 2023

- Published5 October 2018

- Published10 May 2020